Why should I believe you? Why should you believe me?

Behind our beliefs, there looms the figure of Authority. Can we effectively evaluate the truth of a claim without dealing with what authority we trust?

Behind our beliefs, there looms the figure of Authority. Can we effectively evaluate the truth of a claim without dealing with what authority we trust?

How discussions are pre-loaded for failure.

This is the sixth in a series by Arthur Peña, Charles Randall Paul, and Jacob Hess called “Inevitable Influencers: Why (deep down) we all want—and need—to persuade each other of what we see as good, beautiful, and true.” Previous pieces include “Why Persuasion Should be a Sweet (Not a Dirty) Word”; “The Threat of Persuasion,” and “My Truth? Your Truth? No Truth?”; “The Virtues of Strong Disagreement,” and “Our Judgment Against Judgment.”

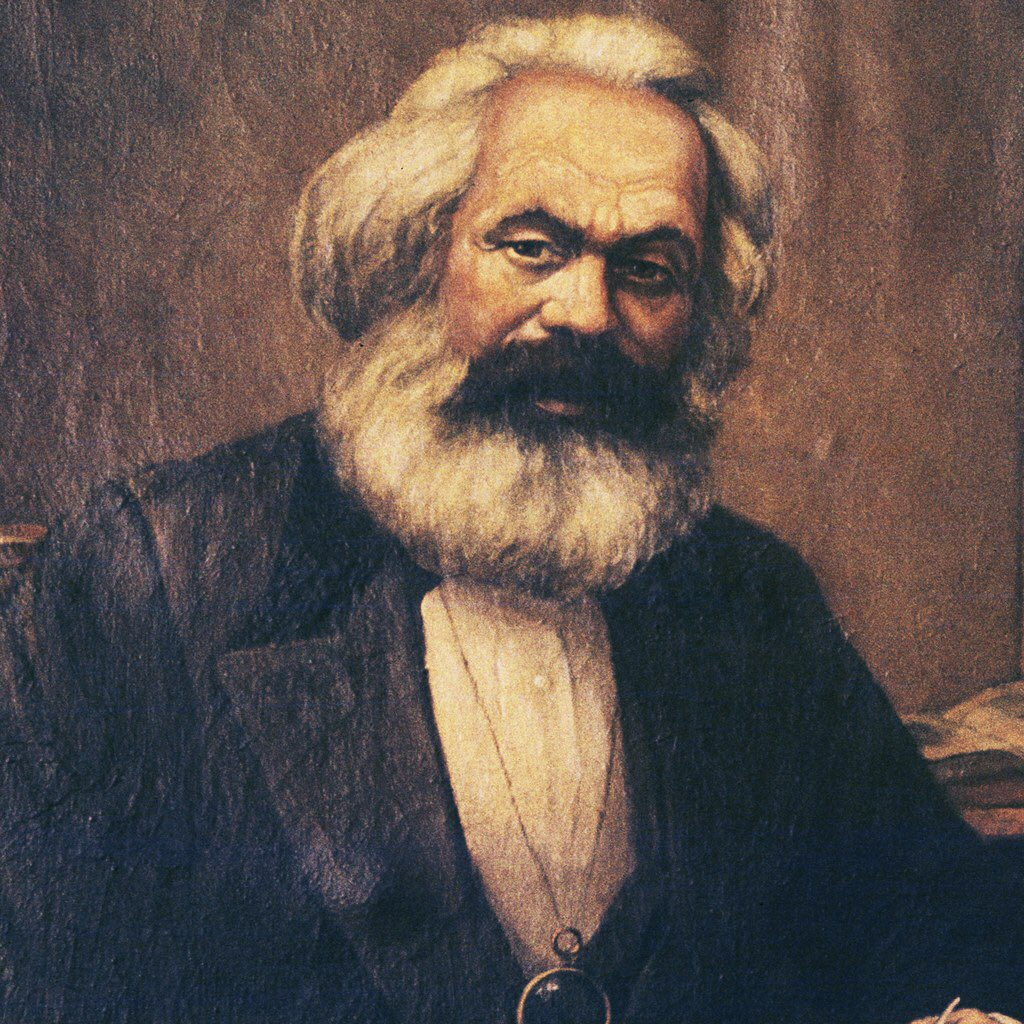

Conservatives worry a lot about Marxism. Yet like other scary groups (Muslims, “Mormons”), often it is loud critics who get heard the most. What do self-identifying Marxists have to say about this American moment?

Being judged for being “judgmental” has become so commonplace we hardly think twice about it. But sound judgment says we should.

Serious differences generate serious discomfort for us all. Could that be why they’re so good for us?

The dwindling sense of a common pursuit of truth is contributing to a deteriorating public discourse. Maybe it’s time to stand up for the truth about truth.

What if deeper conversation threatens my very sense of self? In most cases it is infinitely worthwhile to engage in such “rival contestation.”

Bernie Sanders’ campaign has raised many questions about socialism, communism and even Marx. What does an unabashed, thoughtful Marxist think of it all?

Endless sales, politicking, and bickering have convinced many to see persuasion as a bad thing (“as long as you don’t try and persuade me”). We’re going to try and persuade you otherwise.