The first time I was taught how to craft a literary analysis, my high school English teacher outlined the process.

- Write your thesis

- Find your evidence

- Outline

- Write

Perhaps more discerning readers will already note the obvious error of deciding on a thesis and then seeking out the evidence. Nevertheless, this approach carried with me through seven more years of English education and an undergraduate degree.

So when I wanted to prove that a Shakespeare monologue was trying to show a character with a salivating appetite, I found an M alliteration and wrote it was “literally mmm mmm good.” My exhausted professor wrote “You’re actually good at this. You should take it seriously.”

Texts do mean something—something discoverable, discernable, and fixed.

Through the dozens of literary analyses I wrote, I started with whatever thesis amused me and then hunted down whatever justification I needed to convince others it was true. I wrote award-winning essays suggesting that A Doll’s House was anti-feminist literature and that Twilight was feminist literature (French feminism).

I never approached literary analysis as a rigorous pursuit towards the truth of a piece, but instead as a game. Literary analysis was little more than Balderdash, convincing my peers that whatever idea I had just constructed was the truth cobbling together whatever evidence I could scrape from the text—but without the cathartic aha moment of turning the card over and revealing the actual truth.

Still, the temptation toward using literary analysis to make a text say anything presupposes that the text says something. And while, yes, precocious students could abuse the methods to get texts to appear to mean something different than what they do, that means that texts do mean something—something discoverable, discernable, and fixed.

Reader response theory, from the larger umbrella of postmodernism, approaches literary analysis in a different way. Rather than looking for the meaning of a text from the author’s intent or the words themselves, reader-response theorists suggest that any meaning comes from the readers. And while this has been widely adopted by literary theorists, there remain some notable concerns.

John C. Poirier, Chair of Biblical Studies at Kingswell Theological Seminary writes that when literary theorists adopt reader-response theory instead of trying to understand the author’s intent, they leave their readers in a “tangle.” Literature, he argues, only exists because an author wanted to say something. So when theorists try to analyze what a text means, the only honest way to do that is to discover that intention, otherwise, we’re ignoring the very nature of its existence. Poirier goes on to suggest that just because it may be impossible to figure out with 100% certainty what an author intended, does not mean that we should abandon that as a goal.

In my estimation, Poirier’s analysis goes too far in dismissing the “reader-response argument” entirely. Reader response theorists bring many useful tools to the work of analysis, such as noting that readers bring their own background into understanding a text. But ultimately, as Poirier notes, the theory doesn’t encourage the analysis to move beyond those predispositions but to almost fixate on them.

In essence, reader-response theory suggests that the text means whatever you, the reader, think it means. And while that can make the literary gymnastics I enjoyed much simpler, it robs many readers of the close reading that good analysis would otherwise require.

Moral relativism, which shares many of reader-response theories’ philosophical roots, similarly looks to each individual’s understanding. When this technique is applied to morals the consequences are clear. But as my cavalier undergraduate attitude demonstrated, for a literary theorist there don’t appear to be any real consequences to inventing an even absurd idea and trying to prove it from a literary text. But are there? Are there negative repercussions to not taking texts seriously as an intended message from an author?

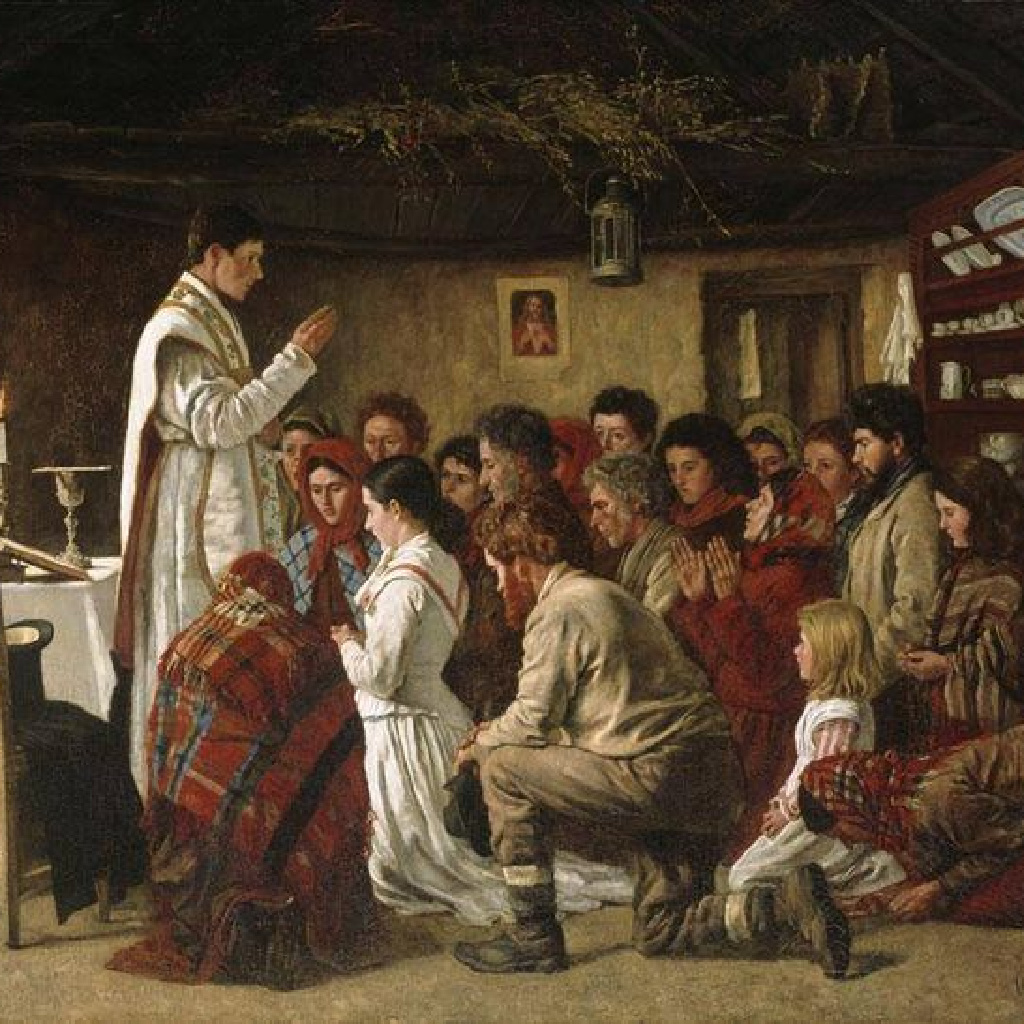

For the religious, the answer is a clear yes. For instance, how to interpret scriptural text has eternal significance. And what is exegesis if not literary analysis?

When it comes to understanding scriptural text, we encounter all the same temptations that I went through in my own brief literary analysis career. There are at least as many Biblical interpretations as there are Christian sects, each with carefully considered evidence to support their ultimate religious thesis.

It might be natural to assume in this context that Latter-day Saints, whose leaders have frequently spoken out about moral relativism, would be similarly averse to reader-response approaches to sacred text. But in practice that is often not the case.

We hear the reader-response theory often in our buildings. Sacrament meeting talks often include mentions of scriptures with special meaning to individual speakers. And pleas of “that’s how I understood it” can be an easy way to share different interpretations of a particular verse without generating conflict in Sunday School.

In his 1st Nephi: a brief theological introduction, Joseph Spencer addresses this type of reading head-on: “1st Nephi isn’t meant to be primarily a collection of illustrative stories . . . we’re free to read it that way, and maybe we’re right to see what we can learn by reading it that way. But Nephi asks us to read his work primarily in a different way.”

Spencer does not diminish the personal value of seeking devotional lessons in the scriptures, but he suggests that through rigorous reading we can better discern the intended message of the author. And when the author is a prophetic messenger, discerning the intended message comes with some urgency.

So in recognition of my weary professor, perhaps it’s time that we take literary analysis seriously, especially in matters of spiritual significance.

BYU’s Maxwell Institute has begun a new series of “Brief Theological Introductions” to the Book of Mormon that approach this very task. The series divides the Book of Mormon into its individual books and has some of today’s preeminent Latter-day Saint religious scholars approach the theology of each book individually. The first two volumes are available, while the remaining are forthcoming.

Spencer’s 124-page entry on 1 Nephi provides not only serious insight into the meaning of 1 Nephi but models an approach to scriptural analysis that will benefit its readers.

Before diving into Spencer’s own approach to analysis, let’s stop to look at one other frequent temptation for readers of 1 Nephi—focusing on whether or not the book is true.

Like seeking devotional lessons, this is a worthy project. As Spencer points out in his first chapter, when Nephi begins the book providing his biography in the first person he “directly invites us to reflect on its origins.”

But while Nephi does invite this question, that is not the purpose of his writing. So, focusing on whether or not the book is true can distract us from the message that Nephi is trying to tell us. Moving beyond these important questions can allow us to read the Book of Mormon on its own terms, perhaps even giving us the tools to better answer the question of validity once we return to it.

Instead, Spencer takes a strict intentionalist approach to the text. He begins with the time and place of writing. Nephi explains that he wrote 1 Nephi many years after the events in question and that he spent nearly ten years writing and compiling the book.

This context helps justify our close reading of the text because we can reasonably assume that it has in fact been carefully constructed.

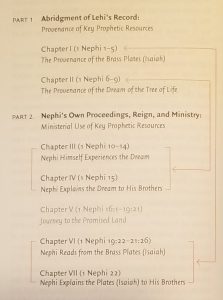

Spencer then moves towards organization. Here he does not use modern chapters, but the original chapter demarcations that Nephi himself would have carefully considered.

Spencer identifies a structure where the narrative of the book’s first half prepares for the prophecy and explications of the book’s second half.

By starting from the context of Nephi’s composition and then moving towards the metastructure of the book, Spencer is able to identify where Nephi himself wants to point the reader’s attention.

Our familiar reader responses to the book fall short in this regard. We often ignore the portions of 1 Nephi difficult to understand, and consequently, we may miss the cruciality that Isaiah’s prophecies play into Nephi’s intended message. Spencer’s approach helps avoid this pitfall.

Spencer does not start with the conclusion that 1 Nephi is about faithfully going and doing, and building a narrative around that, nor does he start with the conclusion that 1 Nephi is a warning against behaving like Laman and Lemuel.

Spencer starts by taking the text as a whole, and allows it to funnel him towards its message, one that probably wouldn’t be at the top of mind for even avid readers of 1 Nephi: the gathering of Israel.

But as Nephi writes in the days after his brothers had separated themselves from the family, the message of future unity suddenly seems like precisely the urgent message that a historical Nephi would have wanted to point towards.

Rigorous intentionalism informed by formal analysis is able to illuminate elements of 1 Nephi that are simply missed by becoming quickly distracted with a reader-response approach.

Once Spencer is able to narrow in on Nephi’s intent, he is able to illuminate its significance in meaningful ways. If Nephi’s intention is to focus us on the Abrahamic covenant, then one purpose in the book coming forth in 19th century America may have been as a wakeup call to a Christianity that had “symbolized away” the Abrahamic Covenant.

None of this diminishes the benefits of readers bringing their own experiences to the text and drawing personal lessons from it. In fact, the second half of Spencer’s book is devoted to just this, taking up concerns that many readers have with Laban’s death, the treatment of Laman and Lemuel, and the often hidden women in the text.

But by allowing the text to speak for itself first, Spencer allows us to answer those later questions from a perspective of understanding its author:

Once we’ve heard 1 Nephi speak in its own voice—once we’ve experienced the entry hall as intended . . . we’re more likely to receive better answers if we’ve first become genuinely familiar with the room.

For example, once we understand Nephi’s focus on the Abrahamic covenant, we might conclude that Nephi framed the command to slay Laban as a kind of Abrahamic test.

Of course, there is no way to know for sure. But as Poirier pointed out, just because discovering an author’s intent perfectly may be impossible, it does not mean that we should abandon it as our goal. And Spencer does not. He draws the author, Nephi, to the forefront of every discussion about the book he wrote.

As the opening book of the Book of Mormon, 1 Nephi establishes the themes, tone, and narrative of what is to follow. If we are lucky enough to have Spencer’s 1st Nephi: a brief theological introduction do the same for the Maxwell Institute’s new series, readers will be very fortunate indeed.