There are few politicians I have had as viscerally a negative reaction to as Donald Trump. He was the first Republican president I did not vote for. And it frustrated me that so many of the most thoughtful, brave, and patriotic people I know would line up behind this man.

So it came as some kind of a relief in the early days of the Trump presidency when there was a collective gut check from the legacy media. Ken Stern the former CEO of NPR was one example of trying to dive into understanding the kind of people who voted for Trump. And for a moment I hoped that Trump’s victory would prompt us to see each other more fully and lessen the othering that has become so endemic to our politics.

Welp, that didn’t work out.

I have spoken frequently of my concerns about how Trump played a significant role in the coarsening of our dialogue. But here, I’d like to talk about the dehumanization of Trump supporters, especially around the issue of QAnon.

I have deep concerns about the number of Latter-day Saints who responded in a recent survey that they endorse QAnon, Peggy Fletcher Stack, recently articulated those concerns well.

So rather than revisit those concerns again, I’d like to focus more on how this recent QAnon survey has been used not just to raise concerns, but to suggest that those who said they support QAnon on a survey are dumb and unworthy of consideration.

This dehumanization is troubling, first of all, because it’s always troubling. But second of all because claiming to believe in QAnon on a survey likely doesn’t communicate what many assume it does.

Let’s take the first survey question. Imagine for a moment that you’ve chosen to support Donald Trump, and have felt frustrated over recent years by media outlets consistently validating the worries of 67% of Democrats that believed Russia tampered with vote tallies to elect Trump, without any evidence, but gave no comparable leeway to Republicans who have similarly believed evidence-free conspiracies about this election.

You feel frustrated, unheard, and resentful. After all, most all Christians believe everything before that hyphen—that Satan is influencing those institutions.

Now you can say no because you simply don’t believe that. Or you can say yes because you completely do. But there’s a third likely group we’re not acknowledging, who believe it partly. After all, most all Christians believe everything before that hyphen—that Satan is influencing those institutions. The point is chances are good you might say you agree, even if you don’t—at least not about the ridiculous part.

As Ross Douthat wrote about conspiracy theories in 2019, while the details of QAnon are clearly false, “the premise of the QAnon fantasia, that certain elite networks of influence, complicity, and blackmail have enabled sexual predators to exploit victims on an extraordinary scale — well, that isn’t a conspiracy theory, is it? That seems to just be true.”

And if you believe the larger message of corruption and depravity, why would you publicly defend those institutions on a survey?

So what percentage of those who answered “yes” to that first question in fact believe QAnon conspiracy theories about satan-worshipping pedophiles, and how many feel powerless and resentful and saw another way to register frustration and “stick” it to those they believe hurt them.

This combines with several other questions the survey identifies as QAnon conspiracies, but which could well be held by many reasonable people. Such as: “There is a storm coming soon that will sweep away the elites in power and restore the rightful leaders.”

Latter-day Saints in particular who believe that Christ will return “soon,” may believe this as a simple matter of faith.

Other beliefs such as “The 2020 election was stolen from Donald Trump” are ambiguous enough that someone could reasonably believe it without subscribing to conspiracy theories (for instance, by someone believing that the election was stolen from Donald Trump by “turncoat never-Trumpers” who they see as abandoning the Republican party).

Other questions such as “The coronavirus that causes COVID-19 was developed intentionally by scientists in a lab” have recently gone from a conspiracy theory to being enough on the radar to warrant ongoing study.

Another contributing factor may be those frustrated with the polling industry because of what they perceive to be a leftward bias, and potentially see this as an opportunity to simply troll the results—or folks on the left who see an opportunity to make the other side look bad.

All told, it’s likely the percentage of those who believe QAnon conspiracy theories is much lower than polls suggest. In so many cases, the people who are claiming to believe in these counter-cultural conspiracy theories are deeply alienated and feel their most cherished assumptions are under attack.

But shouting “it’s not true” to the performative QAnon type doesn’t work. After all, they already know. And the existence of this performative element ultimately obscures the number of those who have truly been hoodwinked versus those who are merely along for the ride.

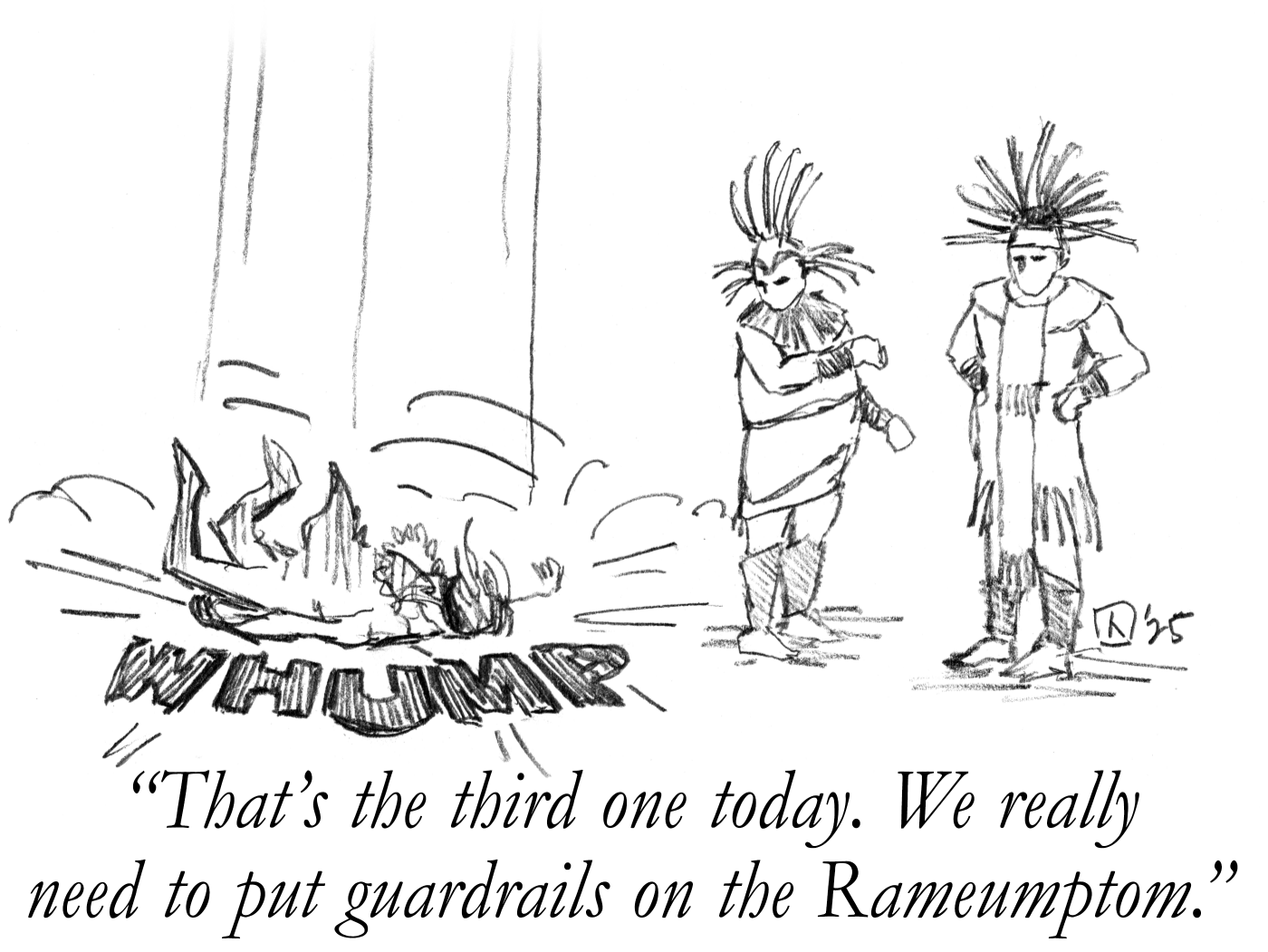

In so many cases, the people who are claiming to believe in these counter-cultural conspiracy theories are deeply alienated and feel their most cherished assumptions are under attack. And since so few intellectually coherent defenses of traditional morals are found in the public square, they perhaps come to rely on conspiracy theories which at least give them a weapon for confronting their unarticulated grievances.

Ultimately, I believe we should be skeptical of these “what do you believe” type survey questions since they often operate as identity questions. In our deeply divided atmosphere, many hear the question “Was the election stolen?” as “Did you vote for Trump?”

Of perhaps greater significance, focusing on QAnon conspiracies obscures how truly bipartisan believing in conspiracy theories can be. Questions about whether Bush knew about the 9/11 attacks or AIDS was created by the US government would likely produce a much different partisan profile.

Yet in today’s partisan atmosphere, a survey or article tying religious or Republicans to conspiracy functions effectively to make them look uniquely dumb, silly, and irrational.

In all this, we could use more of the curiosity around this subject like that Peggy Noonan demonstrated in her recent article examining the social factors that have led to the rise in conspiracism. Even with all the shock that insinuating conspiracy belief elicits in our prevailing American conversation, in the end, this kind of argument may end up meaning less than we think. For instance, writing a headline that the religious are more likely to believe in QAnon likely means little more than the religious were more likely to vote for Trump, and we already knew that.

QAnon is indeed a ridiculous theory. But as Douthat warned in that same article, while most conspiracy theories are false, dismissing them immediately risks “ignoring an underlying reality that deserves attention or investigation.”

The reality here is not that the religious or Trump supporters are dupes, but that the last four years have only served to deepen our divide and increase our alienation. And that certainly deserves our attention.