Recently, we published an open letter to CRT advocates on the BYU campus (and elsewhere) in which we hoped to start a constructive dialogue around what has become an increasingly frustrating and contentious issue. As is usually the case, most of the public criticism leveled against our letter assumed bad motives or deployed vague assertions that our conclusions could only be explained by insufficient effort or inquiry on our part (with no evidence ever offered to support such claims). Yet among sincere respondents, an important theme emerged: the feeling that social conservatives were more invested in fighting antiracism than in addressing racism itself.

That’s a fair assessment and one we hope to begin addressing here.

In what follows, we address social conservatives as we make the case, from our view, for why we need to talk about race in America. Whatever reservations you may have about Critical Race Theory, it’s worth asking why so many people are drawn to this topic right now. The most obvious answer is that progressives are creating the very unrest they seek to alleviate—that CRT and antiracism campaigns are designed to inflame race relations in order to legitimize a power grab by the woke elite. There are undoubtedly such bad actors and those who unwittingly prop them up. Those dynamics shouldn’t be minimized or ignored.

And yet, such legitimate concerns rarely account for the entirety of the problem. What if part of CRT’s appeal is that it addresses deeply important claims to which the liberal tradition in America has, unfortunately, been blind? And what if, in our rush to either advance or condemn the policies and ideas which have—incorrectly or not—come under the flag of CRT, social conservatives are continuing to leave those claims unanswered, with dire consequences for our peace as a nation?

As the anti-CRT message continues to turn populist, it seems to us a lot of dust is getting thrown in the air—leading ordinary folks to have a difficult time teasing out the real issues from the distortions on both sides. The end result then is that discussions about race and racism become just one more region where polarization and misunderstanding complicate everything.

Before we begin unpacking some of those possibilities a couple of caveats are in order: First, even though Blacks are not the only minority in America, we think it’s useful to separately address racism as it pertains to the black community. Slavery and segregation in the United States were a unique set of atrocities—in scope, magnitude, and duration—perpetrated against people of African descent. While other ethnic minorities have faced discrimination and even violent persecution, the transatlantic and domestic slave trades were uniquely despicable and destructive in their consequences for Black Americans, who make up the second-largest minority in the United States. For these reasons, we limit our discussion here specifically to race relations between the black and white communities in America. Not all discussions about race today are motivated by a desire to increase racial distinctions.

Does race really matter?

If we believe that every person is equally valuable and possesses equal dignity regardless of race, aren’t we encouraging racism (many have wondered) by continuing to focus so much on race? Cultural heritage is a deeply meaningful part of human identity.

Not all discussions about race today are motivated by a desire to increase racial distinctions. In fact, for many people, race is a topic of concern because they see differences between the black and white community and they wish to better understand those differences. For instance, a recent study done by the Brookings Institute found that generational poverty persists much longer in black families than in white ones. If we truly believe that all people have equal worth, we should want to know why the blight of poverty continues to disproportionately affect one race more than another and does so over generations.

While we believe that no person is inherently more or less worthy on the basis of race, we can also recognize that because American laws and culture have not always historically reflected this ideal, it’s possible that improved attitudes and interracial relationships have not yet erased the effects of those earlier failures. Race legally defined nearly every aspect of a Black American’s life until the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and it was virtually the only thing that defined them to our larger culture prior to the end of slavery a hundred years before that. Is it, therefore, unreasonable to believe it has continued to assert a social and cultural influence even since then?

Cultural heritage is a deeply meaningful part of human identity. It does not simply reflect a place one is from. It’s a language, traditions, sacred beliefs, rituals, art, music, food, and dress. It’s a particular set of contributions that your kin have given to the world. It’s an immediate community as well as a needed separation from the chaos of the larger world. It’s no more nor less than a kind of home and in the case of African Americans, that home within our world was destroyed—cruelly and deliberately—by slavers. So many long-standing family, tribal, political, and religious distinctions were thus dissolved into the unifying but otherwise uninteresting fact of mere skin color.

In this sense, blacks in America have been given little choice about whether to care about race. Race as an all-defining matter is something that has been, in a multitude of ways, thrust upon them. Anyone genuinely concerned with justice, social cohesion, compassion, and aspiring to the good in civic life should want to better understand that burden.

Does race continue to affect blacks and whites differently today?

Many who reject antiracism or other CRT-inspired narratives about race believe that prioritizing the experiences of minorities on matters of race inevitably leads to “reverse racism.” However, is it really so hard to believe that the average white person doesn’t fully understand the average black person’s experience with racism?

We are not suggesting that no white person has ever experienced racism—nor questioning the reality of some level of real understanding across races. We are simply asking whether something we frequently take for granted in other areas of life applies here—namely, that some knowledge is only gained through experience. Because whites are the majority race in America, it may not be possible in many cases for them to readily or easily understand how it feels to be surrounded by people who are predominantly not of the same race. Even white people who live in predominantly black communities may still be blind to the ways in which the norms of our culture and entertainment cater to white people.

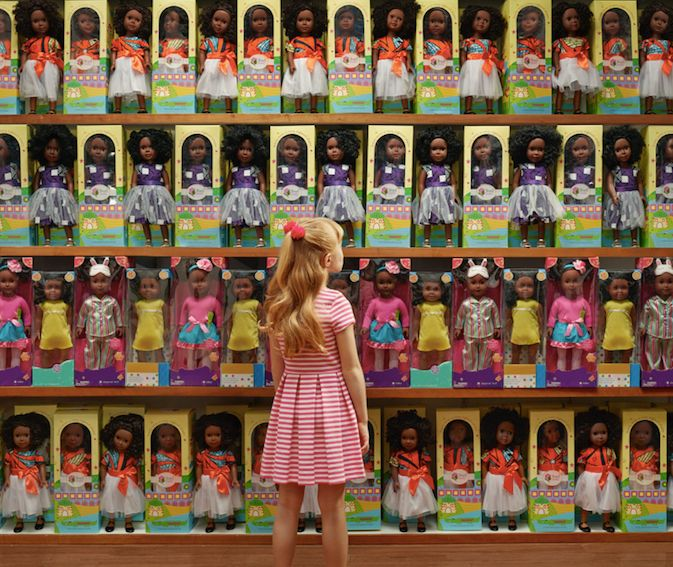

For example, even aside from questions of intentional or overt racism, the idea that a minority can experience the world color blindly may be naive. Consider this photo by artist Chris Buck:

Is it possible for a black person to grow up in a predominantly white country without being continuously confronted with the idea that being white is normal or even ideal? We aren’t suggesting this message is intentional, only that the sheer number of white people inevitably creates a culture that features–and favors–whites.

For instance, consider some of America’s most popular children’s literature: Harry Potter, The Chronicles of Narnia, The Little House on the Prairie, The Hardy Boys, The Hunger Games, The Boxcar Children, Goosebumps, Anne of Green Gables, The Magic Treehouse, etc. Most of these books have no black characters and none have a black protagonist. Most works of classic fiction in the Western canon are also predominantly about white people. One can imagine a black child asking herself why they can’t find popular books about black people or by black authors.

Literature, of course, is not the only part of America’s history and culture in which black contributions have been conspicuously absent. Nearly all the acknowledged contributions we learned about in school–in politics, science, or the humanities–were by white people. If America’s cultural history were displayed as a series of photographs, the casual observer might conclude that only a handful of blacks ever lived here before the 1960s.

Despite the fact that blacks have lived alongside whites since the founding of our nation, they still live in a country and culture that is predominantly white. We are not arguing that this is part of an intentional effort on the part of whites to assert cultural dominance, nor do we believe it a remedy to wantonly dismantle Western traditions. We are only asking other Caucasian Americans, including those in our own faith community, to more carefully consider how such experiences might be largely invisible to them and how that continues to unsettle race relations in America.

And while it’s possible that classically racist incidents are being overcounted (as we queried previously), it’s also equally possible that White Americans are blind to very real, though often quite subtle, racism around them. Even if racist attitudes are relatively rare in America (and we believe they are), it wouldn’t take much critical self-reflection to validate and better appreciate the worry and suspicion blacks might feel. As David French writes:

Let’s perform a thought experiment. … Let’s optimistically imagine that only one out of 10 white Americans is actually racist. Let’s also recognize that—especially in educated quarters of white America—racism is condemned and stigmatized. If this is the reality, when will you ever hear racist sentiments in your daily life? The vast majority of people you encounter aren’t racist, and the minority who are will remain silent lest they lose social standing.

But imagine you’re African American. That means 10 percent of the white people you encounter are going to hate you or think less of you because of the color of your skin. You don’t know in advance who they are or how they’ll react to you, but they’ll be present enough to be at best a persistent source of pain and at worst a source of actual danger. So you know you’ll be pulled over more, and in some of those encounters the officer will be strangely hostile. The store clerk sometimes follows you when you shop. A demeaning comment will taint an otherwise benign conversation. Your white friends described in the paragraph above may never see these things, but it’s an inescapable part of the fabric of your life.

This is how we live in a world where a white person can say of racism, “Where is it?” and a black person can say, “How can you not see?”

[We found Washington Post columnist Jonathan Capehart’s moving personal essay on the same theme especially illuminating earlier this spring—highly recommended, for a better sense of this experience]

Is it really impossible for historical, state-sponsored discrimination to still have lingering effects today?

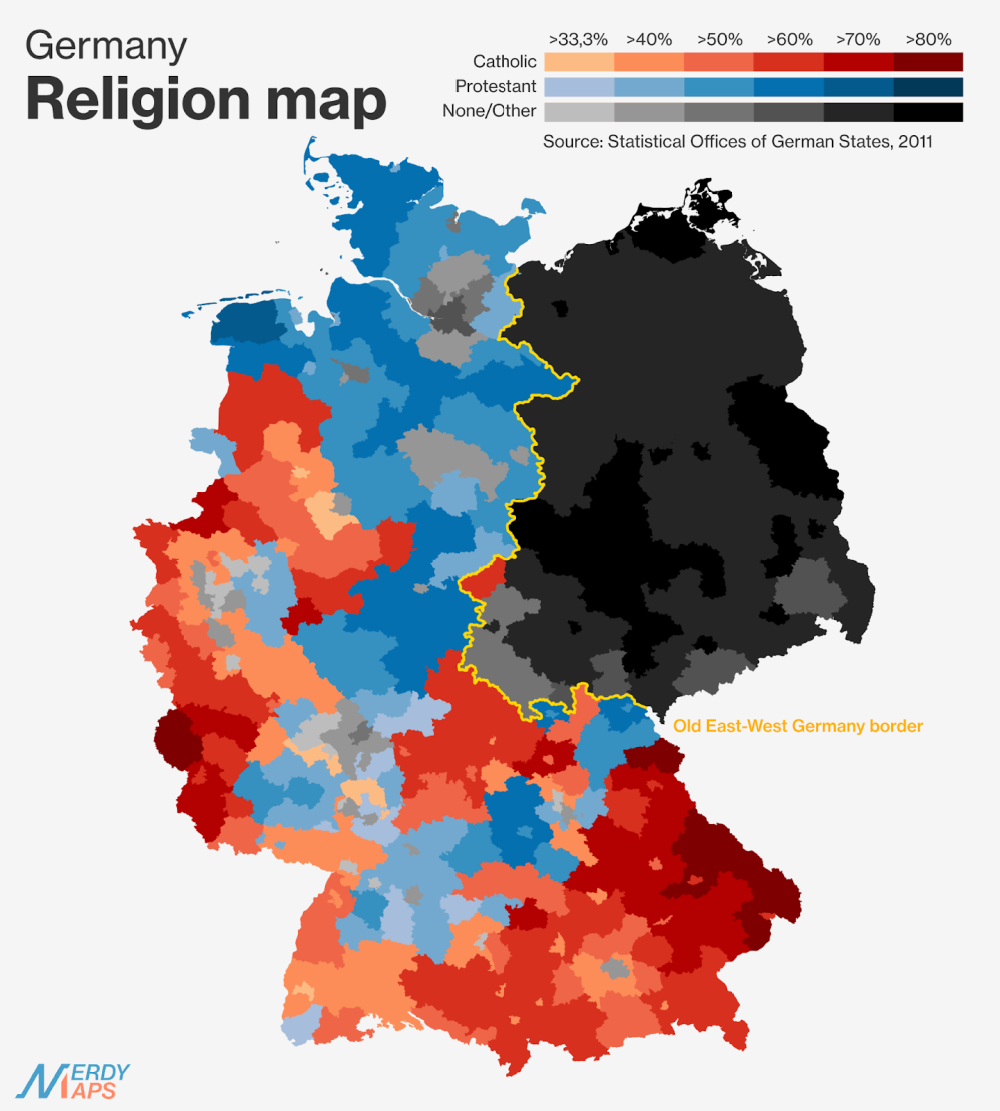

Take a look at this map of religiosity in Germany. Decades of state-sponsored oppression of religion have tremendous effects 40 years later.

Furthermore, statistics show that the single greatest predictor of your income—irrespective of race —is your parent’s income. Yes, income mobility is a thing, but how much money your parents make has a measurable influence on how much you make. Given this well-established connection, is it any wonder that Black Americans have measurable income disparities today, and is it really impossible for this to be a lingering effect of historical injustices?

In short, we would expect state-sponsored suppression of religion to have untold, intergenerational impacts on religious communities long after those policies had been ended. Why not the same for race?

Sure, we’ve come a long way, but wouldn’t we expect it to take a few generations (at least) to wash out the effects of any kind of systemic, especially violent discrimination? And isn’t it totally understandable that some look at present disparities and feel a little resentment, wondering to what degree their present struggles are due to historical injustice?

Even if we disagree on the solutions and approaches to rectifying this, is it not understandable that some may also look with contempt on the implication that income disparities are due to individual moral choices—especially given the particularly heinous moral choices of past generations which deprived their ancestors of the ability to own private property or accumulate wealth? We believe classical liberalism and the U.S. Constitution are indispensable elements in the fight against racism.

Is it inappropriate for black Americans to question deeply held American ideals and traditions?

According to Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic, “Unlike traditional civil rights, which embraces incrementalism and step-by-step progress, critical race theory questions the very foundations of the liberal order, including equality theory, legal reasoning, Enlightenment rationalism, and neutral principles of constitutional law.”

To be clear, we believe classical liberalism and the U.S. Constitution are indispensable elements in the fight against racism. Even so, would you feel beholden to principles of liberalism, American constitutionalism, or other foundational elements of western tradition and culture if …

1) you believed they had historically been used to undermine people of your heritage

2) your race had been explicitly barred from participating in their development

3) their creation occurred in tandem with the purposeful destruction of your own (African) traditions and culture?

In other words, isn’t it understandable that Black Americans might be less invested in the history and culture of a country in whose formation they were often denied self-directed participation? CRT is famous for its challenge to classical liberalism and constitutionalism. But is it any wonder that problematic ideologies like this get traction when so many Black Americans don’t see themselves reflected in our constitutional history?

Is it really “anti-American” to recenter certain aspects of our curriculum?

As social mobility increases among Black Americans, they’re entering fields that have traditionally not had as much black representation. And they’re discovering that many of the people who made significant contributions in their field were not only white but often racist. Since racism was so prevalent throughout certain periods of American history, it might seem obvious to most of us that this would necessarily be the case. But, how would it feel to discover that your intellectual heroes would likely have looked down on you because of your race?

Improved American history curricula do not have to be anti-patriotic or politically partisan. It seems to us there are many kinds of potential improvements that may give our students a more well-rounded view of both the history and the present, better-preparing students to serve their communities and their countries in the future as informed, devoted citizens. If Thomas Edison benefited tremendously from the insights and work of Lewis Latimer, who has largely been ignored in the history texts, is it really a threat, as some seem to see it, to seek out and elevate those contributions, when doing so can help our fellow citizens be more represented and see themselves in our shared history?

We don’t carry our history into the future as such. We carry the stories we tell about our history into the future. And to at least some degree, how we tell those stories is a choice. “History is written by the victor,” and for a very long time, Black Americans were not victors. Many conservatives dismiss out of hand the notion of white privilege and it is indeed a term of modern invention. But what it describes was a historical reality in 1650, 1750, 1850, and even 1950.

Is it unreasonable to question whether the history we teach has fully recovered from this one-sided narrative? We’ve all seen, perhaps, examples of this recentering taken too far, with attempts to “decolonialize” every aspect of our culture and school curriculums, or framing the entire American founding as an effort to enshrine racism and white-centered power structures. But just as the body’s immune system, in the presence of foreign invaders, can sometimes go on overdrive in damaging ways, is it possible that many social conservatives are resisting legitimate attempts to correct historical slights?

Then-presidential-candidate Joe Biden may have overstated the matter when he asserted that a black man invented the light bulb. But in the heartburn over this supposed “historical revisionism,” is it possible that many on the right are ignoring where our teaching of our shared history has neglected important contributions of Black Americans?

At a BYU presentation on race, some participants asked why we have Black History Month, and why we don’t also have a white history month. That’s not a bad question. But rather than dismissing such concern as condemnable bias, perhaps it can be an opportunity to teach that we have a Black History Month and not a corresponding white history month because our history curriculum is already centered on white protagonists and white narratives—not as part of some sinister scheme to assert racial dominance, but as an inevitable consequence of legal and cultural forces which persisted over centuries.

Are modest police reforms really off the table? Cannot a small-government, conservative approach recognize the need for greater accountability?

Conservatives tend to acknowledge the problematic effects of teachers’ unions while overlooking the similarly problematic effects of police unions. Can we not acknowledge the danger and difficulty of police work while striving to increase the accountability of those (few) that abuse the tremendous power with which they are entrusted? What institution is not better served by a culture that embraces accountability for abuse?

Unfortunately over the past year, the primary discussion around police reform in the United has been focused on “defunding” the police. In the relatively few cities where this has been attempted, it’s had disastrous effects, and the policies have been quickly watered down or reversed. We wonder if conservative-oriented reforms could both support and relieve overburdened police officers while reducing civilian-police interaction and the risk of police violence. As writer Dan McLaughlin argued in the National Review in 2020, police reforms can be based on key conservative principles such as respect for all human life, personal responsibility, proportion and deliberation, small government, and federalism, and democratic accountability. Just last week, Public Square Magazine published “Policing Across the Pond,” an incisive reflection on the differences in policing between the U.S. and U.K., which outlines a few practices in the U.K. that American police departments might do well to adopt.

Conclusion

As we’ve observed in other politically charged arenas, the topic of race has become so binary that progress becomes measured in ideological conceits, rather than in lives changed. While a recent story about the racialization of ornithology was picked up by the Washington Post, NPR, Fox News, and CNN, the aforementioned Brookings study about intergenerational poverty among Black Americans was reported by only one outlet: the Deseret News. It’s easy to get lost in a culture war over symbols and forget about the people who need our help.

To those who robustly champion CRT as a new solution to old ills, we would ask the questions of our prior piece. Our concerns are not with antiracism generally, but with the totalizing way in which critical race theory overtakes our worldviews and racializes many important policy disagreements.

To those who relentlessly criticize CRT, we would ask: Is it possible to go too far, thereby ignoring or neglecting real and important issues? And that some are even using the excesses of CRT as a pretext to deny legitimate historical and present realities? We should also ask ourselves: Do we need to calibrate our ideological immune systems a little more carefully, so that we don’t fold every antiracist measure into our criticisms of CRT?

For example, would it not surprise many of us to learn that not all diversity and sensitivity trainings are designed to emphasize white guilt and make us walk on eggshells—and that some of them are actually designed to help us be more sensitive towards and (compassionately) conscious of the experiences of others? (Two favorites we’ve come across include: Chloé Valdary’s antiracism alternative approach, “Theory of Enchantment,” and the new Foundation Against Intolerance and Racism, which we find thrilling in its vision, and in the depth of its diverse, respected leadership; We also appreciate this recent panel discussion by Heterodox Academy on “what Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Training Programs should aim for” as especially fantastic, for the concrete guidance it provides for any campus community wanting to do more).

As reflected here, is it possible that not all efforts to revisit our curriculums are designed to frame the American founding as racist, but rather attempts to include the experiences of Black Americans —our fellow citizens—in that story? Could it be that present disparities in income and influence represent legitimate and unresolved historical injustices—which we can and should look for ways to address? The adversary’s ultimate goal is contention.

The adversary’s ultimate goal is contention. And if the anti-CRT movement sees any conversation about race as “CRT,” and stirs up the masses into a frenzy of contention that way, it serves his purposes just as well.

To brothers and sisters on all sides of this conversation, we would ask: Is it possible to have a more productive conversation on these topics that transcends tribalism, political shibboleths, and straw-manning? Nobody is perfect at this (least of all, us), but we believe Christ blesses the efforts of those who sincerely try. And perhaps more importantly (and directly to Latter-day Saints): maybe those championing CRT are indeed ignoring the threats it poses to our constitutional order—but if we only criticize CRT and don’t also (at the same time), seek to understand and rectify historical racial injustices (even if in ways supportive of constitutional order), are we really taking up the invitations recently extended to us by President Russell M. Nelson and President Dallin H. Oaks?

More good questions to think seriously about, for all of us!