I once began a book review with a story about two brothers. Let me give you two more.

These ones are twins. As kids, they memorize scriptures and pray daily with their family. They’re at church every week. They count cute pennies to pay tithing. Born later, they’d have been poster boys for Come Follow Me.

But freedom’s mysteries are deep, and at fifteen one brother turns away—he doesn’t stop believing, exactly; at first he just stops caring. He tells his parents he’s done with church and they don’t push the issue, hoping it’s a phase. It isn’t. Soon he gets a job, so he can get a phone, so he can do exactly the things with his phone that his parents don’t want him doing. He tries marijuana with friends, drinks at parties, and generally behaves like an ordinary irreligious American teenager.

The other brother continues in the way he was brought up: early-morning seminary, no girlfriend before his mission—of course he’s going on a mission—and strict observance of the Sabbath, the Word of Wisdom, and so on. He gets into BYU, marries, and majors in O-chem. Then it’s off to medical school. He’s going to be a dermatologist.

Does it surprise you that the first brother also becomes a dermatologist? It surprised his parents, but it shouldn’t have. He sinned, lots, but he was careful about it. He never got caught breaking laws anyone cared about, and he never let it hurt his grades. He gets a scholarship to definitely-not-BYU, gets into medical school, and gets the residency he wants—two years earlier than the faithful brother, since he didn’t serve a mission. To everyone’s surprise (justified surprise this time) he even gets married first.

Both brothers move to big cities. They buy two big houses and have two luxury crossovers and two kids apiece. You’d think the faithful brother might have less money in the bank, since he pays tithing, but it doesn’t turn out that way—the other brother’s wine cellar is featured in the Wall Street Journal; he tells them he’s tithing to Bacchus. You’d also think the faithful brother has less leisure time, since he never says no to a calling, but the other brother has hobbies, too, and volunteers at free clinics sometimes. The other brother votes the same as the faithful brother, gives to the same charities (except the Church), goes on the same vacations, and listens to the same music (except, on Sundays, the artists formerly known as MoTab). Really everything seems to even out.

What’s a faithful Latter-day Saint to make of these brothers? To all worldly appearances they’re, well, twins. But spiritually they’re not, right?

Right?

Scripture often offends modern sensibilities, and never more than when the Old Testament tells us that God punishes the sins of the fathers unto the third and fourth generations. And it’s not just the Old Testament; the Book of Mormon has few more puzzling moments than when a prophet tells the Nephites, “Repent or you’ll be destroyed… in four hundred years!” Surely it was the sins of Mormon’s contemporaries, not Samuel’s, that caused Cumorah—right? Then why is Samuel talking about it?

We don’t complain as much when the fathers’ virtues are rewarded unto the third and fourth generations, and maybe that’s what’s happening to our wayward brother. His parents and grandparents invested a great deal in their descendents’ righteous habits, and he’s living like a trust fund baby, drawing down the balance and never quite wondering what his kids will do without it.

Or perhaps it’s better than that. Maybe he’s just naturally virtuous; such people exist, strange though it is to me. Maybe he believes in the sort of life he lives, even without a religion or philosophy to explain it, and maybe he works diligently to hand his virtues down to his children (and if so, God bless him for it).

But what about the faithful brother? Since his twin fell away, he has read the Book of Mormon a dozen times and sat through thousands of talks and lessons at church. He has paid a quarter million in tithing and given two years of his life to preaching the Gospel. He has made weighty covenants in the temple and returned to make those covenants again and again on behalf of the dead.

And what does he have to show for any of it? Outside the narrow part of his life labeled “church,” he dresses, eats, talks, spends, works, plays, and thinks the same as his brother, or his boss, or your average random American of his economic class. And if he lives most of his life indistinguishably from someone who threw his faith to the ground and stomped on it, then what exactly does his own faith amount to?

This is the harder question to me, and the more common. Going off the statistics, or even the Church’s own “I’m a Mormon” videos, you can get the impression that Latter-day Saints are just G-rated Americans—that there’s no fundamental difference between the American Dream and the Gospel. I used to call it “Me-too Mormonism,” back before “Mormon” was verboten and “Me too” started meaning something different. Other Americans become great athletes, and we say, “Me, too!” Other Americans become newscasters or rock stars or investment bankers, and we say, “Me, too! In fact, our faith helps us to be even better athletes or rock stars or bankers!”

“We’re just like you!” we seem to say, “Except we don’t drink, and we have these touching ideas about family—but we’re sure you share those, too.”

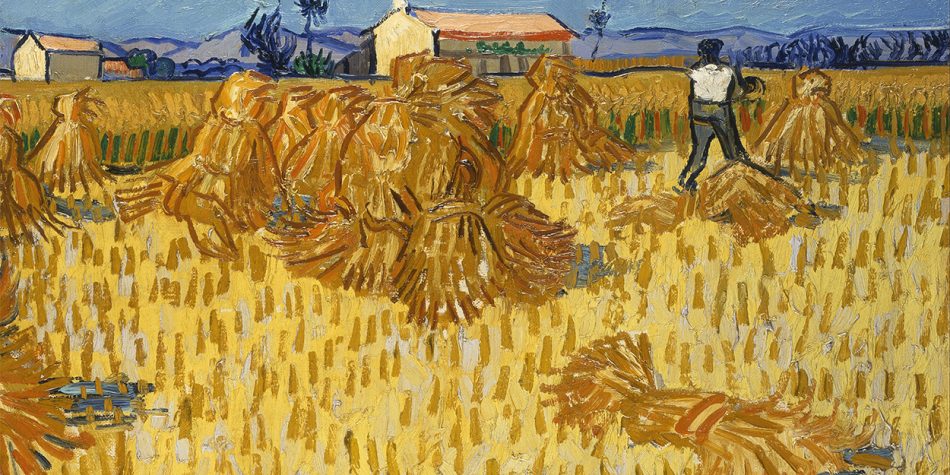

And maybe that’s the way it’s supposed to be. Maybe the Gospel in a Latter-day Saint life is like leaven—the flour and oil and eggs and water are all the same, and it’s not until the oven’s hot that you see the difference. And maybe our two brothers are like a stalk of wheat and a darnel weed; you can’t tell them apart until the field is white and ready to harvest. After all, if you’re looking at the two brothers from the outside, you don’t usually need to know whether you’re seeing grain or tares.

But what about when you’re looking at yourself?