-David Hume

The Jacobin hero of the French Revolution, Maximilien Robespierre, speaking of his legacy said, “Perish our memories, rather than those ideas which will make the salvation of the world.” Louis Blanc later lamented, “Vanquished—his history written by the victors—Robespierre has left a memory accursed.”

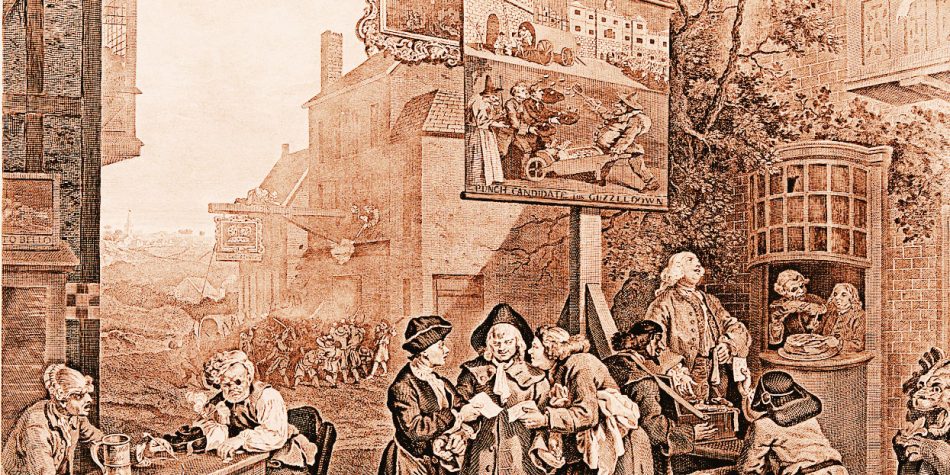

The melancholy phrase that history is often “written by those who hang heroes” is one that helps explain why flustered modern historians often act more like art restorationists, painstakingly uncovering the proper colors to fill in the pieces destroyed by the cruel prejudice of time. What a task it must be to try to repaint a picture as it really was originally and remove away the decay and grime of undue projected biases of the years!

What a task it is to explain an event or character’s significance to its era, a place that is often so removed from us that we can hardly conceive of a time or place when Gunga Rao (a form of capital punishment by an elephant tramping) was used.

Nearly every single influence or residue from the past that is present today has been improved, altered, or had wisdom added upon it. Time itself was even arguably different in prior eras, as lifespans were shorter, and marriage often happened earlier in age. Social ethics were still uncertain and being proved. At some point, a modern student of history finds themselves researching a particular event or notable character and is outraged. “They accepted such vile things!!”

These evaluative feelings and a million more details matter because history is the road map to who and what we have become as an individual, as a family, as a society. Understanding where we have already ventured helps us to grow and not continue to make the same mistakes. There is undeniably more cloudiness as we learn that historical accounts chronicled by early archivists were not made nor kept in the best possible fashion. Sometimes they wrongly assumed that glossing over negative portrayals or characteristics would convey a more edifying message or resonate better with the ethos of the time.

They often made simple accidents of leaving out information that seemed irrelevant at the time, having no foreseeable value, or simply trimmed it out for the sake of conciseness. Often original first-hand knowledge was lost and all that was left was a single account of a person who once read the first-hand account but was not present for the events. Then that account must be translated from French to English in a way that further muddied the original meaning. Even some modern historians or professors will retell history using these archives as irrefutable evidence when in reality, precious little can be counted as verifiably accurate at all.

The Ego Distortion

It’s easy for people nowadays to wonder honestly: How could anyone be so blind as to not accurately portray history free from a range of intrusive influences, including guessing, bias, or worse, agendas of political validation?

In response, we might point out that actually, this uncanny flaw exists within all functioning individuals from the time they are small and first uttered the words, “He started it!” The mind demonstrates an almost instinctive ability to grant its ego all the justification it possibly needs to feel safe in “the blame game”—even if it means clinging to narratives that depart from full reality. As the ego side-steps every accusation it faces, it can be conditioned to prepare the mind to accept immoral acts often with a justification that “it’s for the greater good.” “Do as I say, not as I do,” is the ego’s mantra.

“Whig history” refers to certain 18th and 19th-century British historians who often highlighted, finessed, and modified chronicled accounts to justify the morals and ideals of their present time. Once humans allow themselves to record historical figures from the cozy vantage point of now in a way that justifies or advances their ideologies, the stage is set for presentism.

Every person alive ought to be filled with wonder that their ancestors’ bold risks have shaped today’s understanding.

Presentism is a historical term for judging the past exclusively from today’s knowledge and conceptualizations. If a person writes a book on a historical figure and largely uses present-day values to depict, explain, or infer possible motives to that figure, they are engaging in presentism. Modern historians consider presentism a common fallacy and seek to avoid it because it creates a distorted understanding of the subject.

David Hackett Fischer wrote in Historians’ Fallacies, “To make historiography into a vehicle for propaganda is simply to destroy it.” To further highlight the danger of manipulating history one could add, “To critique history solely by the current values of today is to destroy it.” (Especially for the intent of virtue signaling before inquiring from a more impartial vantage point.)

From a broader view, we might appreciate the extent to which the negative and positive consciousness forged by the past created the mountain of knowledge upon which our modern world stands today.

The enormous advantages of these collective understandings in our day may well suggest (and even implore) that all people have a little epistemic humility towards these foundations as they were built from trial and error. Every person alive ought to be filled with wonder that their ancestors’ bold risks have shaped today’s understanding, even while being keenly aware there is still much to improve upon.

Making Sense of Judging

Which moral judgments are best to leverage as we make sense of the historical record is a controversial subject. Some believe that practicing moral relativism is to avoid moral judgments —wherein what is true for one is not true for all. Thus, morality is circumscribed by our own individual judgments: if you believe that having tattoos is morally wrong and then you get a tattoo, then you are morally bad.

Others believe that since God established morality, it is timeless and unchanging; therefore one can apply eternal unchanging standards to the past. Most often you hear proponents of both camps arguing that the other represents a great danger.

I would suggest that moral relativism and moral absolutism are not at odds here, and may, instead, be revealing truth together. Absolutism provides a sturdy ground upon which a gradual evolution through experience can take place which enhances the proper view of absolutes. If moral absolutes provide the sturdy taproot and trunk, relativism then offers a multiplicity of leaves and branches, and fibrous roots enlarging to address the precise context of the time and place.

On one hand, this contextualized expansion of the proper view reveals details not considered or missed altogether, but now arguably enhanced by it. And on the other, the world cannot lose moral absolutism because it provides a normative vocabulary which is imperative to make sense of the world, and without it, we embrace nihilism.

Obviously, there are many moral truths that are considered self-evident, for example; rape, child abuse, and domestic abuse will always be wrong. While the running over of non-combatants with a truck outside a war zone could also be proposed as always wrong, the details now play a crucial role. This is where moral relativism begins to refine and reveal a more complete moral judgment. Could circumstances exist in which the moral absolute encompasses the intent of both parties? Could the intent of non-combatants be to block the roads in order to trap? Was this running over an accident?

The actual facts of what was understood or accepted in the past are frequently even far less appealing than a dispatched water pup.

Taking into account what a person believes is another important tool for judging character. Thus, one can say it is wrong for a toddler to hit, but when considering what the toddler experiences and understands, a better judgment can be made. If not widely accepted, I find this blending of both concepts valuable in my own efforts to make sense of history.

In doing our best to evaluate historical issues, one must hold to their own moral convictions, while also accepting that people did what they knew, and they could not do better if they didn’t know better.

As David Hackett Fischer once said, “No man is free from the logic of his own rational assumptions unless he wishes to be free from rationality itself.” Although it may be practically impossible to set aside our internal biases, perhaps it will suffice to simply be more cognizant of not distorting the historical facts in line with our own disgust or liking.

How great was a great historical figure in his or her time in which they lived? How did they contribute to what you now know? What were their intentions? From this mindset, we might conceivably honor a caveman who clubbed baby seals but saved our entire species by the invention of the wheel. Sadly, the actual facts of what was understood or accepted in the past are frequently even far less appealing than a dispatched water pup.

For instance, how are we to judge Felix Hoffman, to whom is attributed the development of two drugs, Asprin and Heroin? This might seem simple at first glance but the decision seems to become even hazier the further back in history we travel. This happens almost inevitably because our primary records become less abundant, less reliable and the characters less likable as the acceptable customs appear so deplorable. How are we to view British Lord and Protector, Oliver Cromwell nicknamed “Old Ironsides”, who helped overthrow two monarchies but also despised Catholics to a near-genocidal view? How should we look at Cristoforo Colombo? Known now as Christopher Columbus, many falsely trust that his writings were translated perfectly even though the original writings are physically lost and historians are skeptical towards the Bartolome De Las Casas copy. Is it at all possible Columbus has become a scapegoat of blame for the horrifying problems that already existed during his time? How confident are you that you learned his history as it actually was, not defiled by whiggishness, presentism, statements clipped out of context or translated incorrectly?

Another set of important questions that make a point might be this: Can we no longer appreciate historical places such as the Parthenon, Rome’s Forum, and the great pyramids, all of which were built by slave labor? Should we continue to pull down the statues and buildings of our past? Should we stop tours at Auschwitz? Even in places where sickening events occurred, are there not still lessons worth remembering?

As the facts of the past are examined, details must be fleshed out, free from preconceived judgments, in order to properly frame them for present-day considerations. Poor dichotomies of “all good vs all bad” should evolve into more detailed and comprehensive viewpoints. Indeed, when we see people taking the most cynical view possible of history, we have to wonder how would any of us fare? Human beings are complex—and if the most cynical portrayal of any of us individually were made, would it represent the full truth of the matter?

Clearly not. So if we’re interested in “the full truth” we have to move beyond either “full cynicism” or “full glorification” by asking deeper, and less contrived questions.

Was this historical event or person significant for its time? Are we sure history was recorded properly in a trustworthy manner? Was the person or event helpful to society of its era—or of a subsequent period? Did the person or event generate the impetus for new lessons in failure or success? This pattern of asking a myriad of incisive questions before passing judgment should be repeated with a great many historical events and influential figures.

For example:

- George Washington owned slaves. (Yes, that is sickening!)

-

- Was this the acceptable behavior of the day? (Yes. 40% of the Virginian population was enslaved during his time.)

- Was this a life he was born into? (Yes. He inherited slaves at 11 years old when his father died. Brutal punishments for bad behavior were taught and considered normal justice at the time.)

- How did he treat them? (Many recall him being very strict and rigid. Slaves were accused of stealing, working slowly, and faking sick. 7% of the slaves tried to run away.)

- Did he enjoy the idea and practice of slavery? (He grew increasingly uncomfortable with the practice the older he became. He decried it in the Fairfax accord. He was the only slave-owning founding father who freed all the slaves that were solely his, upon his death.)

- If YOU were raised to know nothing but being a master to slaves, then given slaves at age 11, would YOU have been a slave owner too?

- Did Washington’s actions help set the stage for Abraham Lincoln’s later Emancipation Proclamation?

- Should we honor George Washington’s life or legacy of building America even though his life also demonstrated some reprehensible practices from our present view?

Once details like these are fleshed out, one could both say that slavery is inexcusable and diabolical while still being able to see how and why it happened and what historical contributions were made by a slave owner to set in motion events that eventually led to ending the practice.

In closing, I would argue that society’s present state of knowledge is one of mitigated ignorance and someday all present today will likewise be judged by future inhabitants on what has been accomplished, overcome, wrestled with, and embraced. Hopefully, the future of the world’s populace will view our current actions with both the truthful facts in hand and a nuanced appreciation of context. Hopefully, they will also be people grateful to have learned from the triumphs and the disastrous failures of our own day.

May we continue to look backward and discern as best we can the lessons of the past for our day. As Robert Heinlein once said, “A generation which ignores history has no past and no future.” These ominous words meet equal hope when paired with the words of Thomas Jefferson, “I like the dreams of the future better than the history of the past.”