Perhaps every bishop becomes acquainted with the acute risk to bishop–youth–parents relationships from unintentionally but unavoidably placing youth in the position of bishop–parents liaison or go-between—because, of course, parents care for their child and want to be in the loop. We’re all familiar with the telephone game, where a message is passed from one person to the next, down the line to the end. We’ve all been surprised to see how the message morphs. Do we understand that children always are and will be the formal or informal go-between or liaison between the bishop and parents? Bishop, youth, and parent communication in shared spiritual ministry on behalf of youth can be at risk if it takes the form of the telephone game. Readily recognizing this risk, many bishops likely establish preferred patterns of open communication. Avoiding the telephone game and realizing the full potential of shared bishop–youth–parent ministry is possible as all work together to establish a collaborative spiritual ministry. Through collaborative counseling, there is potential to avoid or work through misunderstandings.

The developmental pile-up of the teen years can be very stressful for youth. When being a go-between between the bishop and their parents is added to the mix, the stress is magnified and could lead some youth to isolate in anticipation of it all. Youth who know that their bishop will sensitively facilitate positive parental involvement—beginning with open communication—can be encouraged to rely upon their informal bishop–youth–parent council for support. Ideally, parents too will shoulder this responsibility and commit themselves to youth-focused purpose and interaction. We have named this informal commitment a bishop–youth–parent council, a support structure that helps youth feel loved and supported and avoids placing them in the middle as the bishop–parent go-between.

Even with open communication, differences can and indeed often do occur when caring individuals view challenges from different angles. Yet differences need not divide us, and there is a better chance of ensuring that they won’t where there is open communication and council deliberation. Where open communication in informal bishop–youth–parents councils reveals different inspired perspectives, commitment to collaboration and keeping the family unit centered can help priesthood leaders work sensitively for unity borne of the Spirit’s gently guiding influence. Commitment to collaboration and keeping the family unit centered can help priesthood leaders work sensitively.

Conversely, with prayerful preparation and inviting of the Spirit, our common purpose to help our youth can instead gather together from a diversity of perspectives, a unity of heart, thought, and action, magnifying counsel and ministry through the collective revelation spread among us. All this is possible as bishops, youth, and parents alike seek the humility to accept that, indeed, “revelation is scattered among us” and is brought to a unity of divine purpose through Spirit-guided council process. If indeed revelation is scattered among us, it would seem to suggest that an informal bishop–youth–parents council collaboration is virtually imperative to amplify and magnify inspired youth counsel and ministry. “Counseling [together] allows [a bishop, youth, and parents] to gather that revelation,” each adding a piece of the puzzle that will portray their shared ministry.

A bishop–youth–parent council provides a setting for gathering that collective revelation for inspired ministry. Throughout this process, humble parents and leaders need to be sensitive to conforming to the framework for personal revelation that the apostles and prophets have outlined. Spirit-guided processes will never lead to division or disunity, discord or contention (3 Ne. 11:28-30), or to opposition or outright rejection toward priesthood leaders sincerely seeking inspired guidance. Rather, the promise is for gentle guidance and nudging toward unified ministry (Isaiah 30:20-21), as is often spoken of concerning deliberations in the Council of the Twelve.

Understanding boundaries of stewardship and authority becomes very important. It is also important for the bishop to be careful to bring the parents alongside, lest a rift develop. This is no different, though, and less problematic and ultimately less time-consuming than where the parents are not invited in and only hear second-hand information the phone-game way.

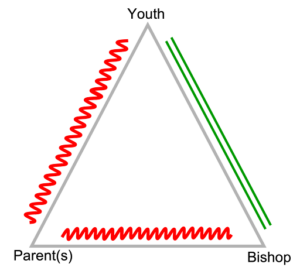

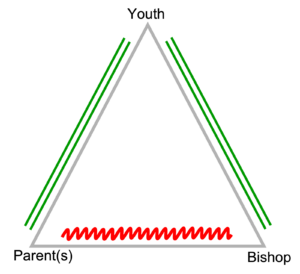

In the graphics accompanying the stories below, a straight green line indicates confidence and positivity in a relationship, while a squiggly red line indicates strain or uncertainty in a relationship (sometimes there is simply a relationship to be established, sometimes there is a rift or rupture to be repaired).

Andrea’s Experience: A Bishop–Parent–Youth Challenge and Opportunity

Andrea is 17. As depicted below, she has a good relationship with her bishop, while she feels anxious in her relationship with her parents and also about their relationship with the bishop.

Andrea has recently started viewing pornography. Her Young Women group recently met to discuss the law of chastity and one of her leaders mentioned how pornography was bad but that she didn’t need to talk about it because “I know that none of

After Andrea meets with her bishop and discloses her pornography use, she also shares her fears about her parents. Andrea asks the bishop to meet her parents and explain the situation to them because she is anxious about how they will react. The bishop agrees, and after Andrea leaves his office, he asks her parents to join him. The bishop shares directly with Andrea’s parents his love and compassion for Andrea and his counsel for repentance. Sensing the bishop’s sincere care for Andrea and respect for them, Andrea’s parents respond well—a few tears, some frustrations about Andrea not choosing to share with them, but arriving eventually upon a shared desire to be a help to Andrea, above all else, a caring and striving that unites them. After a few minutes of preparing themselves to focus unitedly on helping Andrea, they invite Andrea back in. Feelings and fears are shared and calmed. Working together they all come up with a plan on how to help Andrea and decide that future meetings will involve Andrea, the bishop, and her parents—whether one after the other or all together will be left up to Andrea. Trusting relationships all around are strengthened, and Andrea and her parents are closer than before and prepared for Christlike ministry. Andrea’s parents’ availability to her is of paramount importance to the bishop.

There are clearly potential land mines to be avoided, and we commend the bishop’s decision to first strengthen the trust in his relationship with Andrea separately and then seek to build his relationship with her parents. Can we envision the potential for family and ecclesiastical relationships to grow and be strengthened all around from careful bishop–youth–parent communication promoting ministerial collaboration, helped along by their shared love for Andrea?

Other situations with potential for phone game problems rather than clear and open communication include helping youth prepare and qualify to serve as missionaries, determining whether a proselyting or service mission or two-transfer mission will be the best fit, uniting with a missionary and priesthood leaders to help an elder or sister finish their missionary service earlier than anticipated due to physical, emotional, or mental health challenges and working together to decide whether an honorable release, transition to a service mission, or preparation to return to a proselyting mission will be best. All these represent common and especially vulnerable situations, and each is also a critical opportunity for uniting and collaborating to help youth remain steady in the gospel, committed to Church activity, and firmly on the covenant path.

Maya’s Experience: Bishop–Youth Strengthening the Youth–Parent Relationship

Maya is 17 and a recent convert to the Church. As depicted below, Maya’s relationship with her bishop is just beginning, but is trusting and hopeful, though she feels a bit anxious. Maya has a loving, positive relationship with her parents, but she is worried about a strained relationship developing between her parents and the bishop. Maya’s parents allowed her to be baptized—a bit reluctantly—but they are not enthusiastic about or highly supportive of her decision to pursue religion.

It is vital to establish trust from the very start. If parents are receptive, a brief, informal visit with the parents in the home to describe the church experience and convey the Church’s commitment to honor and support family relationships can help build trust. Honoring the family and parents in this manner invites softening, trust, and a peace-promoting witness of the Spirit.

The bishop first meets with Maya, shares the importance of her family ties and influence, and asks her how they might proceed to help her parents gain greater comfort and confidence regarding her church choice. The bishop also helps Maya understand that inviting a positive bishop–youth–parents relationship is for the best, since the Church exists to support the family and since parents likely have a legal right to be informed. Family-centered, church-supported means honoring parents in their divine role.

Maya’s scenario, like others, presents both challenge and opportunity. Meeting with Maya’s parents is both appropriately respectful and an opportunity to build a trusting relationship between the bishop and parents and also invoke and strengthen bishop–youth–parent fellowship (a precursor to possible collaboration). The inspired potential is tremendous. The necessity is apparent. The doctrinal basis is clear—family-centered, church-supported means honoring parents in their divine role, whether members or not.

Miguel’s Experience: A Priesthood–Missionary–Parent Challenge and Opportunity

Miguel is 19. His mission president has counseled with him concerning his health struggles in the mission field and a decision has been reached for him to return home where he can receive family support and professional help. As depicted below, separate consultations among and between his mission president and himself, and between his mission president, stake president, bishop, and parents—all sincerely focused on helping Miguel—has nonetheless produced a web of telephone game uncertainty and confusion with real potential for misunderstandings, which could place priesthood–youth–parents relationships at risk of a rift or rupture. There are numerous matters involving youth that are, like this one, fraught with vulnerable emotion.

Recognizing the growing risk, Miguel’s mission president arranges a conference call—a “ministry team meeting”—to establish relationships, invite collaboration, develop the plan, and unite all in helping Miguel thrive spiritually and otherwise across this transition.

As can be seen in the experiences of Andrea, Maya, and Miguel, establishing and sustaining sensitive, respectful communication all around, with an intentional effort at avoiding telephone-game dynamics, is the first level of bishop–youth–parents unity and cooperation. Through such effort, family and church relationships can be strengthened and made an integral part of spiritual development. In place of a telephone-game dynamic, communication between ecclesiastical leaders, youth, and parents should perhaps be more like the old-time party line, with every covenant relationship respected through an open line of communication. Beyond communication, or building on that foundation, lie opportunities for real collaboration, mentoring, and mediation, which can carry family relationships toward truly Christlike ministry in the home. These will be discussed in Part 3 of this series.

Subscribe To Our Weekly Newsletter

Stay up to date on the intersection of faith in the public square.

You have Successfully Subscribed!