As Christians around the world prepare to celebrate Easter, there are stark reminders all around us that many people in the world today need hope. Although we live in an era of unparalleled abundance, material prosperity alone cannot cure many of the ailments that afflict people in modern society. So, what if anything can?

19th-century Christian writer Simon Greenleaf once suggested that if Jesus Christ really did rise from the dead, it changes everything. It’s worth asking ourselves this week: What hope can the Resurrection of Jesus Christ provide for those who lack hope today?

When I have thought about the resurrection in the past, I have most often focused on what is going to happen in the future without giving too much thought about what might happen today. For example, I love quoting the prophet Amulek’s vivid description of our future resurrection (“both limb and joint shall be restored to its proper frame … and even there shall not so much as a hair of their heads be lost”). This is one of my favorite scriptures, and it brings tremendous comfort in relation to all the unfairness and disadvantages that this life can bring. But it is definitely focused on something that will happen in the future. What about the here and now?

In thinking about this question, I believe that Latter-day Saints can learn a great deal from New Testament scholar N. T. Wright. Wright has shared countless insights about the resurrection over the years, including how the resurrection offers hope for the present world. The Resurrection of Jesus Christ is the greatest evidence we have that what is impossible in human terms is possible to God.

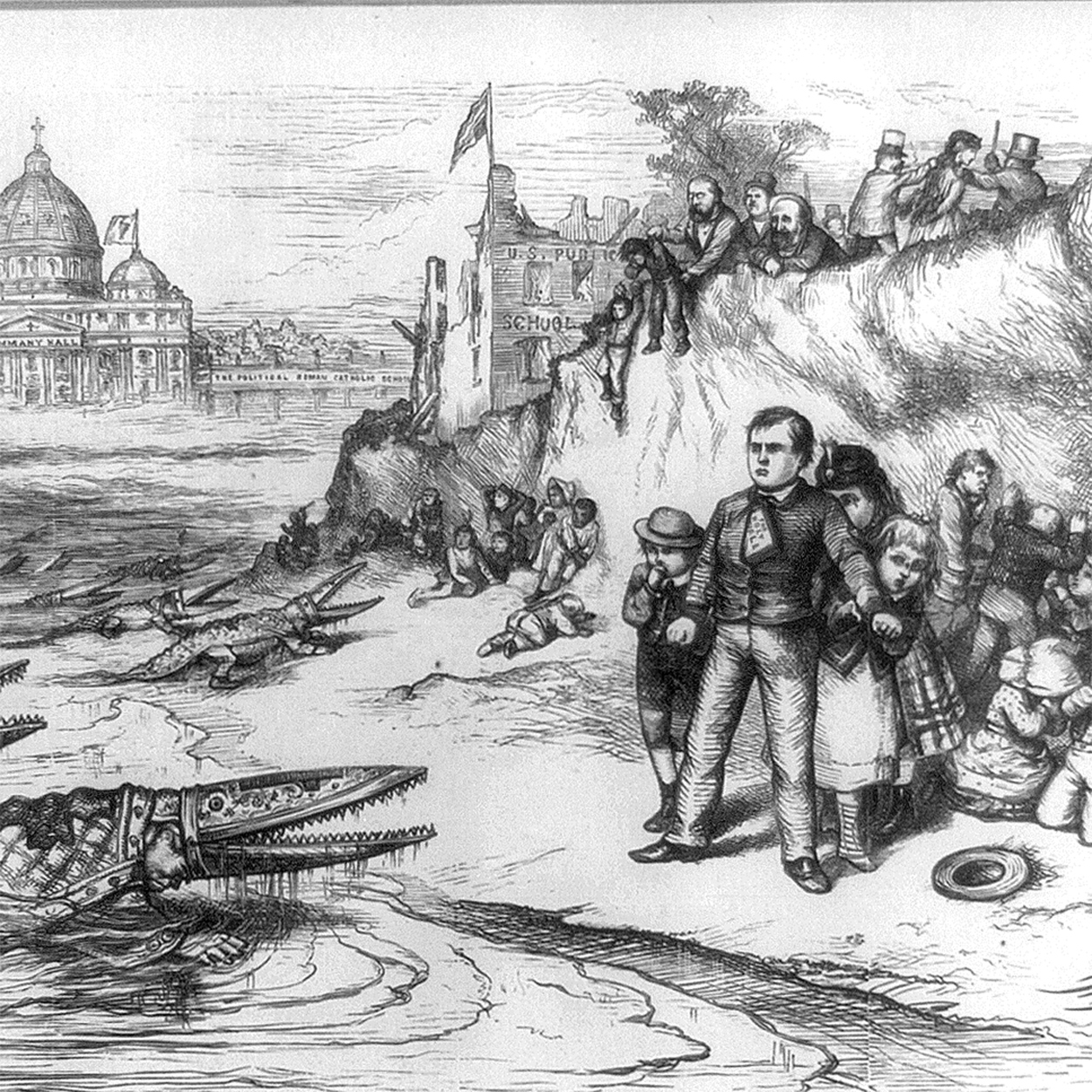

This bears some semblance to the Christian view. The problem, however, is that this perspective is typically expressed without any reference to God. And in a purely secular context, there are plenty of reasons to be skeptical that humanity will be able to reach utopia by means of our own efforts alone. Among other things, the many horrors of the twentieth century serve as sobering reminders of our proclivities toward sin and evil. Moreover, as Wright correctly notes, “even if ‘progress’ brought us to utopia after all, that wouldn’t address the moral problem of all the evil that’s happened to date in the world.” Nor would it address the problem of death — both on an individual basis and as a collective human family. Without God, we are left with the harsh reality that (as Bertrand Russell puts it) “all the labours of the ages, all the devotion, all the inspiration, all the noonday brightness of human genius, are destined to extinction in the vast death of the solar system, and … the whole temple of Man’s achievement must inevitably be buried beneath the débris of a universe in ruins.” So much for the myth of progress.

The second perspective that Wright discusses is essentially Gnosticism (or at least something quite close to it), namely the idea that “we are made for something quite different, a world not made of space, time, and matter, a world of pure spiritual existence where we shall happily have got rid of the shackles of mortality.” I can’t help but hear echoes of Gnosticism in the modern view of the self. I agree with Wright that “if you move away from materialistic optimism but without embracing Judaism or Christianity, you are quite likely to end up with some kind of Gnosticism.”

This perspective, however, offers no hope for this world—it is, rather, an escape from this world.

Wright goes on to argue that Christianity’s view of the future of the world “combines the strengths and eliminates the weaknesses” of both the secular belief in progress without God and the quasi-religious tendency toward some type of Gnostic spirituality. Above all, the focus within Christianity is on redemption, and the Resurrection of Jesus Christ teaches us about what that means:

Redemption is not simply making creation a bit better, as the optimistic evolutionist would try to suggest. Nor is it rescuing spirits and souls from an evil material world, as the Gnostic would want to say. It is the remaking of creation, having dealt with the evil that is defacing and distorting it. … What God did for Jesus at Easter He will do not only for all those who are “in Christ” but also for the entire cosmos. It will be an act of new creation, parallel to and derived from the act of new creation when God raised Jesus from the dead.

In other words, Wright is saying that the ultimate redemption of the world—the ultimate Christian hope—is in some important ways analogous to the Resurrection of Jesus Christ. This has profound implications for our world today. For one thing, it means that the redemption of the world as a whole is actually possible. While such redemption may seem impossible right now, given all that is happening around us, so does raising someone from the dead. The Resurrection of Jesus Christ is the greatest evidence we have that what is impossible in human terms is possible to God.

Of course, we cannot transform the world all by ourselves, just like we cannot raise anyone from the dead by ourselves. So perhaps our grand ambitions for social, political, and cultural revolution should be tempered by a bit of humility.

On the other hand, this does not mean that we are off the hook with respect to improving the present world. True Christianity is not an attempt to escape from the present world. As Wright says (emphasis in original): “Precisely because the resurrection has happened as an event within our own world, its implications and effects are to be felt within our own world, here and now.” Just as Jesus prayed and worked for God’s kingdom to come “in earth as it is in heaven,” disciples of Christ strive to bring God’s kingdom to this very pain-filled world in which we live:

The message of Easter is that God’s new world has been unveiled in Jesus Christ and that you’re now invited to belong to it. And precisely because the resurrection was and is bodily, albeit with a transformed body, the power of Easter to transform and heal the present world must be put into effect both at the macro level, in applying the gospel to the major problems of the world … and to the intimate details of our daily lives.

Latter-day Saint author Adam Miller has written along similar lines. In his book, An Early Resurrection, Miller says that “starting a new life in Christ can be described as an early resurrection and … this kind of early resurrection is intended to save both my future and my present.” This is counterintuitive in some respects, but Miller explains it clearly and beautifully:

In Christ, the way I live—my manner of living—is changed from the inside out. Like being in love, living in Christ changes what it means to be alive. Living in Christ, I carry myself differently. I desire differently. I love differently. I greet pain and loss differently. I fail differently. I succeed differently. I part with the past differently. I respond to the present differently. I look to the future differently.

It is my faith that those differences will manifest themselves in a multitude of ways that can and will bring about healing and hope to the present world. Those who truly “live in Christ” will treat family members with greater kindness and sensitivity. They will work to help and support their local communities. They will diligently seek to obey the Lord’s admonition to “succor the weak, lift up the hands which hang down, and strengthen the feeble knees.” They will be more attentive to prophetic counsel about the social ills of our day, whether in relation to ending poverty or racial strife or conflicts of any kind. As a result, families will be strengthened, schools will be improved, civic engagement will be increased, and new job opportunities will be created. As the influence of those who live in Christ continues to expand outward, hope will be fostered at every level of society—including hope about the macro-level problems that seem so intractable right now. While much of this hope is clearly still directed at future events, at least some of it can be directed at what is possible today. “The message of Easter is that God’s new world has been unveiled in Jesus Christ and that you’re now invited to belong to it.”

Every act of love, gratitude, and kindness; every work of art or music inspired by the love of God and delight in the beauty of his creation; every minute spent teaching a severely handicapped child to read or to walk; every act of care and nurture, of comfort and support, for one’s fellow human beings and for that matter one’s fellow nonhuman creatures; and of course every prayer, all Spirit-led teaching, every deed that spreads the gospel, builds up the church, embraces and embodies holiness rather than corruption, and makes the name of Jesus honored in the world—all of this will find its way, through the resurrecting power of God, into the new creation that God will one day make.

This is a glorious, hope-filled perspective—indeed, it is the only perspective I can conceive of that offers any real hope for the present world. And it is exactly what the world needs right now.