Several years ago, I invited our next-door neighbors to attend the blessing of our baby. They were close friends, and it was natural to include them, but I felt a little nervous due to the format of fast and testimony meeting. I wanted to prepare my friends, so in a rambling and awkward way, I told them that on the first Sunday of each month, people freely come to the pulpit and share their religious convictions—and with that, a variety of personalities are on display. My description was tinged with embarrassment and I’m guessing that was obvious to my neighbors.

Fast forward many years to when I was working on my master’s thesis on the ‘Latter-day Saint Talk’ in which I argue that there is the potential for creativity and growth in the practice of lay members preaching to one another. My thesis supervisor effectively did his job by pushing back at my work as he repeatedly emphasized the Church’s hierarchical structure and the resulting limits on what speakers could say. During a particularly challenging conversation, I used the less structured nature of testimony meetings to argue that there is freedom within the constraints. I even described it as an open-mic Sunday to emphasize the very aspect of the meeting that had been a source of embarrassment for me years earlier.

So, why the contrast in how I handled these two situations? Why did I apologize in one but defend in the other? There is freedom within the constraints.

Elder Patrick Kearon recently spoke at a Brigham Young University devotional where he reflected on his first visit to the campus when he was in his twenties and not yet a member of the Church. He described being “stunned in the most wonderful way” by both the physical beauty of the university’s setting as well as by the students who were “eagerly engaged.”

He said something to his audience of BYU students that resonated with me:

You are children of God. You are spirit daughters and sons of our Father in Heaven. I realized as a convert in my mid-twenties that you who were raised in the Church had been raised singing songs that reminded you of this. You were taught this every day—almost day in and day out any time you came to church. And that’s a beautiful strength. But does there ever come a time when there’s a risk if we become complacent in our relationship to that knowledge? When it has been heard so often, when it has been sung so frequently, and when we have said it so much, does it risk being devalued in our heads and in our hearts? I think the answer to that is at least a small yes. To someone who comes into the Church—such as in my case, again, in my twenties—this is a glorious revelation! It is such a powerful, beautiful, fundamental truth.

Growing up in the church is a beautiful strength, as Elder Kearon describes, but it is a strength that comes with the risk of devaluing what we have. He warns of becoming complacent in our relationship to fundamental gospel truths which can also extend to our attitudes of how these relationships are nurtured.

As someone who has grown up in the Church and who carries the risk of complacency, the work of the great hermeneutic philosopher Hans Georg Gadamer (1900-2002) has helped me to see things with new light and beauty, including testimony meetings. He was himself agnostic, but he wrote with an openness that allows his work to be applied to the study of religious practice.

Significantly, Gadamer emphasizes the finitude of human reason, and with that, a concern about the modern overreach of a form of scientific method that does not leave room for other ways of knowing. Gadamer uses the concept of play (spiel) to explore these other ways as he argues that we learn through active involvement. He explains that by engaging in dialogical experiences, where we are not simply objective observers, the line between the subject and object is blurred, and extra-scientific knowledge can be gained. Gadamer focuses on the aesthetic or artistic to illustrate what occurs in play. For example, intentional encounters with texts, paintings, practices, beliefs, and stories can illuminate and reveal truths in a playful way. Think of experiences you’ve had where you were drawn fully in and then emerged with new understanding. This is what Gadamer describes as play. When intentionally participating, everyone can experience the proclamation together.

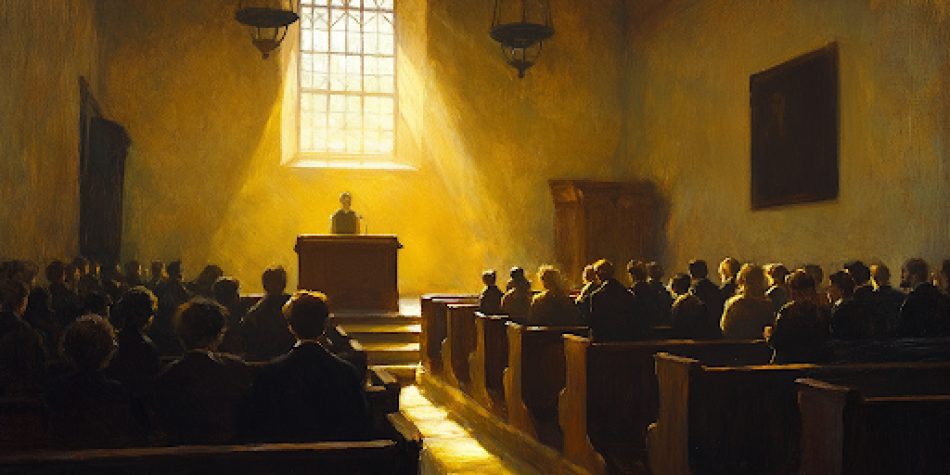

Gadamer uses Christian rites and preaching as examples of play that occur on a religious playing field. Through his agnostic lens, he observes that “a religious act is a kind of playing that, by its nature, calls for an audience” and “the players represent a meaningful whole for an audience.” The congregants are part of the game as they participate through active listening to the gospel message of “Christ’s redemptive act.” Gadamer explains that “The claim of faith began with the proclamation of the gospel and is continually reinforced in preaching … hence it is one word that is proclaimed ever anew in preaching.”

Even from this brief explanation of play, with the specific example of religious proclaiming, it is easy to see how Gadamer’s philosophy can be applied to Latter-day Saint practice. As church members gather in the playing field of a sacrament meeting following guidelines set out by the Church, individuals come to the pulpit and testify of restored gospel truths—truths they have learned through the context of their own lives. A “meaningful whole” is then represented for the congregation who have come together. When intentionally participating, everyone can experience the proclamation together. The sense of representation is further heightened due to the Latter-day Saint practice of sharing and rotating roles. An individual may sit in the pews one week but then stand at the pulpit the next. Everyone is potentially a proclaimer of the gospel “ever anew.”

There is a limit to how far Gadamer’s work can be applied to the Church, however, because his philosophy doesn’t venture into the transcendent with an accompanying spiritual vocabulary. He walks to the edge of belief but does not enter in. He describes proclaiming but doesn’t become a proclaimer himself. Paradoxically, though, the very act of him staying on the precipice of faith seems to highlight the potential transformational power of that position if one chooses to move beyond it.

President Boyd K. Packer’s well-known teaching fits well here.

A testimony is to be found in the bearing of it. Somewhere in your quest for spiritual knowledge, there is that ‘leap of faith,’ as the philosophers call it. It is the moment when you have gone to the edge of the light and step into the darkness to discover that the way is lighted ahead for just a footstep or two. [emphasis added]

The leap of faith is an active one, and it requires intention and effort. And, sometimes, it takes the form of stepping up to the pulpit on a seemingly ordinary Sunday.

My appreciation for the sacred precincts of a fast and testimony meeting has deepened through the years. I have seen the beauty of coming together to testify of eternal truths. If I could go back in time and extend the invitation to my neighbors again, embarrassment would no longer be attached. Rather than devaluing something that has always been part of my life, I’d welcome my friends to a space where I, and many others, have experienced profound meaning and truth.