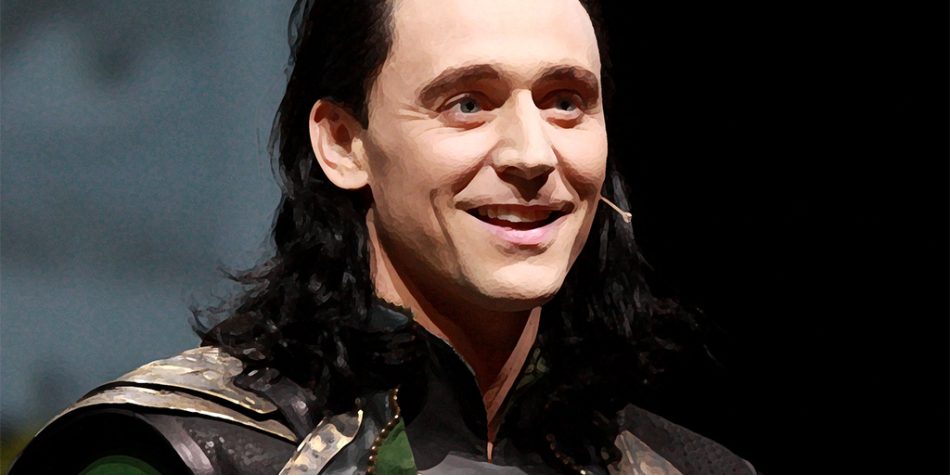

“You’re a big metaphor guy. I like that, it makes you sound smart,” Owen Wilson’s character Mobius observes of Loki, in his eponymous new Disney Plus show.

He’s right, of course, humans love a good metaphor. They help us expand our vision by connecting the new with the experienced. Melissa Burkely, who is both a novelist and a psychologist, wrote, “Metaphors are not just a literary technique; they are a psychological technique.”

We should expect, then, that as society moves into new conversations we will look for metaphors and analogies from the past that can help us understand what is happening in the now and what might happen in the future by comparing it to the past we are already familiar with. But because of the psychological power of these metaphors, we must be careful about which ones we regularly adopt because otherwise belaboring the similarities without fully recognizing the differences could lead us to inaccurate conclusions. After all, remember your English class definition, a metaphor is a comparison of two unlike things. Understanding the way things are unlike is often just as crucial in our public debates as understanding how they are the same.

We will look for metaphors and analogies from the past that can help us understand what is happening in the now.

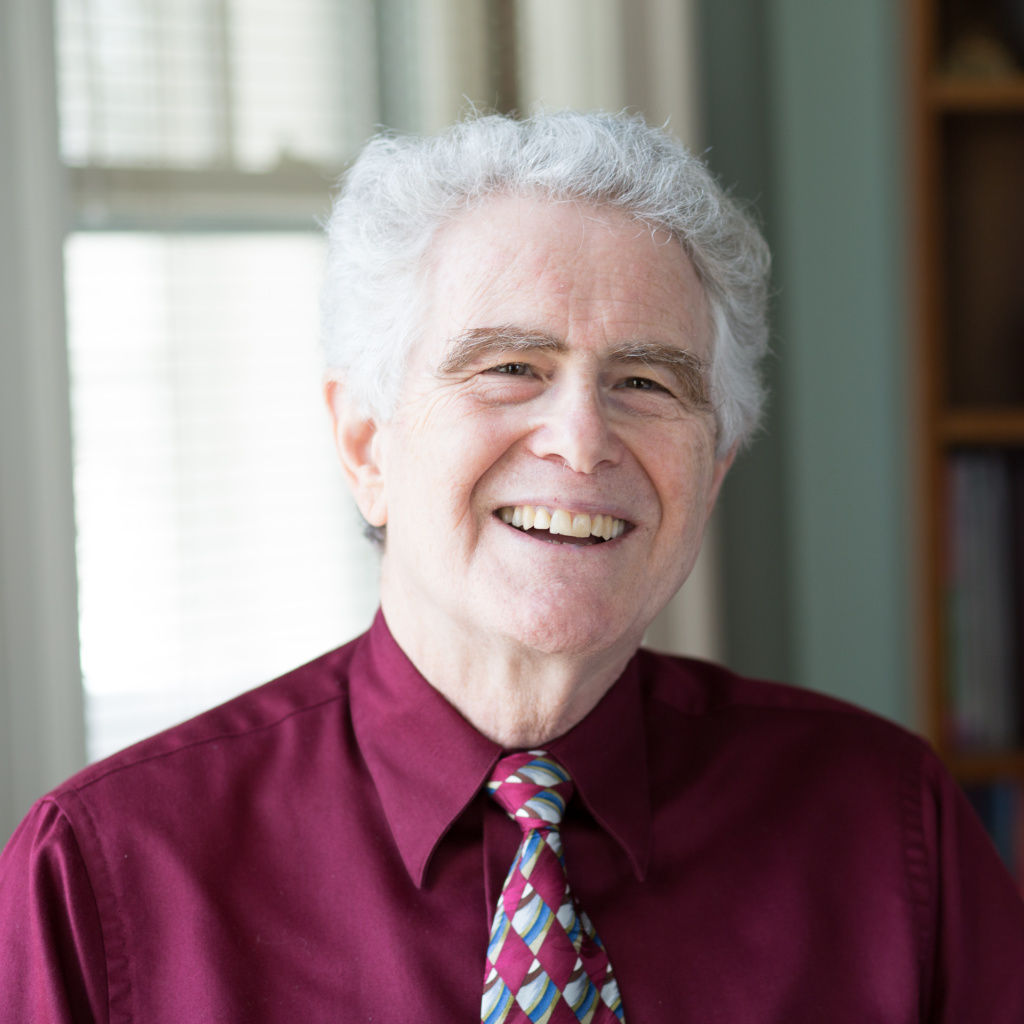

Newly-retired Professor Richard Davis of Brigham Young University used a familiar metaphor in his recent Op-Ed to help understand a contemporary situation. Davis draws the (very) commonly made comparison between the current situation of the Latter-day Saint LGBTQ+ population and the pre-1978 situation of the black members of the Church of Jesus Christ, arguing that it’s God’s will that the Church should perform same-sex sealings just as it was God’s will that the Church should extend the priesthood to all members. I’ll leave it to others to communicate what God’s will for the Church is. You can certainly understand why Davis and others have settled on this metaphor. There are many superficial similarities between the two. But ultimately the historical analogy fails in a number of ways. I have no ill-will towards Professor Davis, but given that this argument is so popular and sows confusion among many Latter-day Saints who want to be on the Lord’s side, it is worth directly addressing.

First, there were always Church leaders who stated publicly that the priesthood restriction would be lifted (while others said that it wouldn’t). No such statements have ever been made at the General Authority level about extirpating the Church’s heteronormativity.

Second, race was a very incidental, very occasionally discussed aspect of Latter-day Saint theology. By comparison, issues of gender, family, and the reproductive imperative (in this life or the next) strike at the very core of Latter-day Saint notions of exaltation. Changing it would require a fundamental doctrinal overhaul in ways that the race issue simply would not. While one can mine past statements of Church leaders to find a quote here or there that implies that the former priesthood ban would continue forever or that the civil rights movement was infiltrated by communists, the Church as a whole has made a concerted effort in the past couple of decades to connect themselves to traditional notions of gender, family, and sex. No such concerted, generalized effort was ever made in regards to traditional notions of race. The conflation of the two, while providing an easy soundbite, can be offensive to traditionally religious people of color.

There are other points that could be belabored. For example, while Professor Davis is an accomplished social scientist, his absolute sureness about what liberalizing the Church would do sounds more like a testimony than the measured thesis of a scholar, and ironically flies in the face of empirical evidence showing that more liberal denominations have the weakest retention rates. Professor Davis is welcome to believe what he wants about the future of the Church’s position on LGBTQ+ issues, but facile comparisons don’t help his case. Professor Davis is also welcome to believe what he wants about God’s will; we are expected to seek out our own confirmation of the Church’s positions, and he is to be commended for doing so, but let’s be clear, being in conflict with the Church on the issue of human sexuality is, in so many important, substantive ways, in a different category than being in conflict with its past positions on race.