Chances are you’ve come across the phrase in the last year. Between best-selling books, breathless coverage on cable news, and well-promoted articles in national news outlets, the phrase “white Christan nationalism” is now googled more often than at any other time in history.

And the consequences of white Christian nationalism are predicted to be catastrophic. President Biden suggested it “threatens the very foundations of our Republic.” Time Magazine called it “the greatest threat to democracy in America today.” Meanwhile, the Washington Post quotes a professor predicting that white Christian nationalists will “become more radical, more militant,” and the author of a New York Times bestselling book on the subject suggests the movement could lead to “an autocrat who delivered on its Christian nationalist dreams.”

It’s a lot to take in. And the pace does not seem to be slowing down. Both the Washington Post and New York Times have written treatments on the subject just between writing and publishing this article. And a book set to be released this January predicts that white Christian nationalism will lead to a civil war.

White Christian nationalism has been on a slow decline over the last thirty years.

There is a real threat, including among people of faith. Many on the right have become quick to dismiss any talk about “white Christian nationalism.” But that’s a mistake.

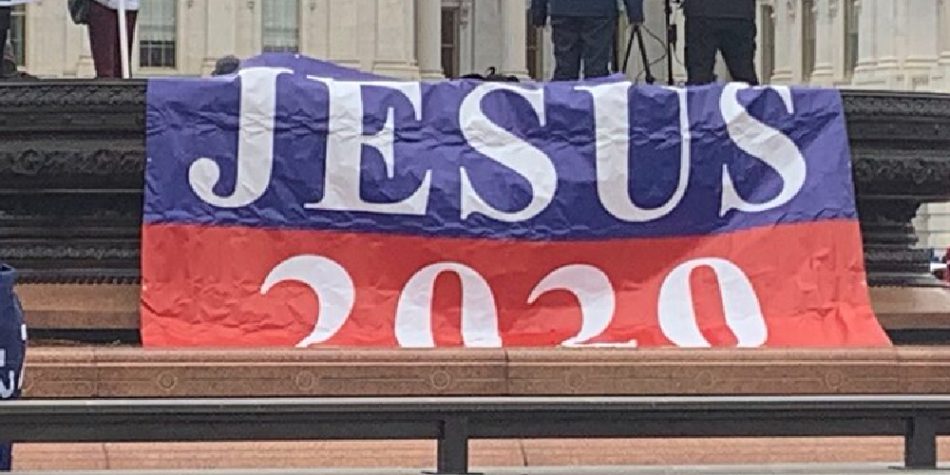

Although white Christian nationalism has been defined in many ways, and expanded in troubling ways (see below), there’s still something at its root that might be widely appreciated as concerning. That includes an uncomfortable fusion of religion and politics, wherein “The church is supposed to direct the government,” in the words of Congressional Representative Lauren Boebert—and where political enemies begin to be associated with outright evil.

Perhaps the most concerning element of what is being called “white Christian nationalism,” however, is an impulse towards aggression—both rhetorically, and in the threat of overt violence. What happened at the capitol on January 6 is the most prominent example, but there are other indications of percolating willingness to consider violence against the government.

This includes a willingness to enforce Christian doctrine in the government—no matter what it takes. This can include violently overturning elections, installing authoritarian leaders, and removing constitutional rights. It’s not that white Christian nationalists don’t care about these things. It’s that in their conception, the rule of law and majority rule are not what define being American, but religious and racial identity. So if throwing away the rule of law and majority rule is necessary to secure a white Christian nation, they will do it.

Any such aggression, of course, is incompatible with religious teaching in many faiths, including Latter-day Saint doctrine. Dallin H. Oaks, the second-most senior leader in the Church, said three months before the January 6th riots, “We obey the current law and use peaceful means to change it. It also means that we peacefully accept the results of elections. We will not participate in the violence threatened by those disappointed with the outcome. In a democratic society, we always have the opportunity and the duty to persist peacefully until the next election.”

Russell Ballard, the acting president of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, has also said, “We need to embrace God’s children compassionately and eliminate any prejudice, including racism, sexism, and nationalism” (emphasis added).

Religious freedom is baked into Latter-day Saint doctrine and history. Our articles of faith claim our own religious freedom and allows that same privilege to all others. And both Nauvoo and early Utah, which were run by Latter-day Saint leaders, had robust religious freedom protections, allowing the free exercise of religion for both Christians and non-Christians alike.

Definitional creep. While there is something at the root of legitimate white Christian nationalism that is of real concern, the scope of the problem is frequently overstated. And the direst predictions are premature and overhyped. In too many cases, the definition of white Christian nationalism has been significantly diluted in order to present it as a much broader problem than it is.

In too many cases, the definition of white Christian nationalism has been significantly diluted in order to present it as a much broader problem than it is, in fact. The CNN article, for example, doesn’t define white Christian nationalism by its anti-democratic or violent possibilities but rather believing that the United States was founded as a Christian nation, believing in a warrior Christ, and the belief that there is such a thing as a “real American person.”

These beliefs can possibly lead to or reflect white Christian nationalist beliefs. But they are not white Christian nationalist beliefs in and of themselves. For example, you could believe that a real American exists, and is defined as a white Christian, but you could also believe a real American exists because you are making a tautological argument about illegal immigration. This is a pattern—measuring beliefs that could but don’t necessarily represent white Christian nationalism—that is found in much research on this subject.

Because people are unlikely to say to a pollster that they believe in violently overthrowing the government, researchers have attempted to find related beliefs that might somehow correspond with white Christian nationalism. But all too often, in public discourse, these downstream corresponding beliefs are then being used to define white Christian nationalism itself, such as in the CNN article.

But CNN is hardly the only perpetrator.

NPR recently published an interview that claimed, “Christian nationalists often rally under a call for religious freedom or religious liberty.” That’s right, NPR cites a researcher who claims that we can discern who belongs to a group that explicitly rejects religious freedom by looking for those who deeply believe in religious freedom.

And while it’s true that white Christian nationalists also co-opt the term religious freedom, assuming that all who believe in the principle are doing so deceitfully is problematic. Are those who call for religious freedom for both Uyghur Muslims and American Jews white Christian nationalists? Only half the time?

Many of these talking points come from research presented in the influential book Taking America Back for God. They defined Christian nationalism by asking six questions:

- The federal government should declare the United States a Christian nation

- The federal government should advocate Christian values

- The federal government should enforce strict separation of church and state

- The federal government should allow the display of religious symbols in public places

- The success of the United States is part of God’s plan

- The federal government should allow prayer in public school

The authors ultimately used these questions to group together everyone who even slightly supported Christian nationalism. It’s easy to see how these questions would identify many people as Christian nationalists who don’t share the ideology. If you are someone who believes students should be able to pray quietly to themselves in school, everything is part of God’s plan, abortion should be illegal, and decorating public spaces should be allowed for all local organizations, you would be identified as a Christian nationalist. This could be true even if you strongly opposed the idea that the United States should be a Christian nation and strongly supported enforcing the separation of church and state.

What the authors of this book recognize that other commentators do not is that these overbroad surveys are good for tracking changes in sentiment over time, not determining accurate numbers at any given time. In fact (and contrary to much of the hype around us), the big-picture takeaway in the book is that white Christian nationalism has been on a slow decline over the last thirty years.

And it’s not just researchers expanding this definition. While President Biden may not have explicitly called out Christianity in his recent speech, he uses rhetoric to conflate those who deny elections and perpetrate violence with the 65% of Americans who believe abortion should be restricted and those that hold traditional views of marriage—both of which he himself believed during much of his political career. Both of these, of course, are common positions of mainstream Christians and other religious believers. They’re hardly exclusive to extremists.

Another way commentators seek to overstate the problem is to claim that Supreme Court decisions are facilitating white Christian nationalism. In fact, a paper with this title found its way into a major law review. Earlier this year NPR stoked fears that “Christian nationalism is getting legal legitimacy through the Supreme Court.” But this is a rather odd conclusion to come to given the unanimity behind many of the Supreme Court’s recent religious freedom cases. This argument requires believing that the Jewish Elena Kagan and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the Puerto Rican Sonia Sotomayer, and the Black Clarence Thomas are all facilitating white Christian nationalism when they decide—for example—that the TSA can be held financially liable for discriminating against two Muslim men.

The idea would be farcical if it weren’t being taken so seriously by so many.

Of course, some claim that it’s not merely laws about religion that are being influenced by white Christian nationalists. Recent changes in abortion law were frequently cited as a result of this ideology—with critics arguing that this was yet another reflection of an insidious attempt to make religious belief—in this case, that abortion was morally wrong—the law of the land.

But this metric is used with remarkable selectivity.

Would it be fair, for example, to accuse Taylor Petrey, the editor of Dialogue, of being a white Christian nationalist merely because he tweeted Bible verses to support President Biden’s recent loan forgiveness? Of course not.

Would it make any sense to accuse Stacey Abrams, the black gubernatorial candidate from Georgia, of being a white Christian nationalist because she says that her advocacy for legalized abortion comes from her “faith in God?” Obviously not, which is why no one does that. Yet, it has become rather popular to claim that if religion motivates a different policy conclusion on abortion you are a Christian nationalist.

As bizarre as it would be to accuse Stacey Abrams of white Christian nationalism, many of these surveys that seek to define it have rather interesting racial breakdowns. According to the influential Taking America Back for God survey, the racial group most likely to be a white Christian nationalist was black Americans, at 65%. It also found 21% of Jews were Christian nationalists.

You know something is crooked when your metric to measure attitudes that seek to place white Christians at the top of the social order is most supported by black Americans, and by 1 in 5 Jewish Americans. Clearly, these surveys are not measuring what they intend to.

Neil Shenvi, a frequent critic of Christian nationalism, summarized the research around this issue, the “approach and methodology is too imprecise, and they’re catching a lot of people in this category that don’t belong there.”

All this has particular relevance for my own faith community. While more than half of all Latter-day Saints have lived outside of the United States for more than a generation, it is still frequently described as “the most American religion.” And because God restored the Church here, we believe that God cared about the founding of this nation and inspired some of the freedoms that allowed that to happen.

Under the broad creeping definitions above, it wouldn’t be at all surprising to see more and more people talk about all Latter-day Saints as falling under this damning label.

Political strategy at work. If the failings of the research in this area are so clear, why are concerns still repeated so breathlessly?

It should come as little surprise that white Christian nationalism is trending just as a midterm election is coming up.

Magnifying the hysteria is certainly an intriguing political ploy. Tying a threat to American democracy to your political opponents, magnifying the threat as big as possible and presenting yourself as the solution is an easy-to-understand political motivation—even if the effect is not inventing the problem, merely exaggerating it.

Much of the focus also likely comes from the recent newsworthy violence perpetrated by white Christian nationalists, such as the Charlotte demonstrations or the January 6th riots. And since the consequences of the success of this ideology could be so dire, it makes sense to be especially sensitive to it. Many core Christian practices are increasingly portrayed as extremist in and of themselves.

Many core Christian practices are increasingly portrayed as extremist in and of themselves. According to a 2016 Barna survey, missionary work, protesting based on religious beliefs, and believing in the traditional definition of marriage were each “extremist” positions according to more than half of Americans. In fact, nearly a quarter of Americans in the surveys believed abstinence until marriage is an “extremist” position.

However politically advantageous they may be, moral panics are extraordinarily divisive. Not only do they harm targeted groups, but they also create anxiety and bad risk assessment decision-making in those who believe in them. The condition was first described fifty years ago:

A group emerges to become defined as a threat to societal values and interests; its nature is presented in a stylized and stereotypical fashion by the mass media; the moral barricades are manned by editors, bishops, politicians and other right thinking people; socially accredited experts pronounce their diagnosis and solutions.

It would be hard to find a more succinct explanation of what is happening with white Christian nationalism today. The author of this definition went on to make the point that the issues are real, but the claims are exaggerated about how serious or inevitable the harm is. All this fear has real-life consequences. I am familiar with people who have had to seek mental health treatment because they are so worried about the effects of white Christian nationalism.

By claiming that those who hold mainstream Christian views are, in reality, extremist or white Christian nationalists, voices like Stewart or those in the survey also seem to hope to fundamentally alter the nature of Christian belief and practice.

The ultimate effect of claiming that believing the government should pass policies in line with Christian values is white Christian nationalism or that protesting policies because of your faith is extremist is to scare Christians out of the public square. And the more moderate Christian positions you can tie to extremism through rhetoric or overly broad surveys, the more Christians you can exclude. In this way, the motivation may be political, but not only in the expedient near-term way we’re seeing today. It’s fair also to wonder about a longer-term attempt to push back on Christian efforts to oppose another insidious but often unnamed ideology, secular nationalism.

Let’s talk about secular nationalism too. In much the same way that white Christian nationalism can reflect a distorted story about the nature of America that can lead to exclusion and violence, secular nationalism starts with a similar story. Namely, this story is that the United States was founded as an irreligious nation. Rather than being neutral to faith in the public square, this story is referenced to underscore an underlying antagonism to faith in civic spaces.

These individuals believe religion should be allowed to exist within the United States, but only if it is kept tightly within the walls of churches and the home. They increasingly use extra-constitutional phrases like “separation of church and state” to describe the state of religious freedom in the country to obscure the actual constitutional protection of the free exercise of religion.

By some measures, secular nationalism is much more ascendant today than white Christian nationalism. In my view, while they have not shown the same willingness to undermine the democratic process, they use rhetoric that is no less exclusionary. And these secular nationalists show extreme willingness to use the power of government to coerce believers to violate their faith and use rhetoric that suggests that the religious should not use their religious principles to participate in the public square. This often happens alongside legal maneuvers to isolate and punish believers. For example, major national publishers have advocated financially punishing non-profit organizations which are religious. Missouri and Montana have recently had policies that punished organizations that were religious (playgrounds and schools, respectively). And support for these policies, which discriminated against people of faith, was widespread.

Others states have also passed laws holding that people of faith cannot work in entire industries unless they are willing to blaspheme their faith by redefining important religious concepts according to government fiat.

These efforts to establish the United States as an explicitly secular nation, rather than, as intended, a religiously neutral nation have had substantial success in state houses—certainly more than white Christian nationalism. Yet they have received virtually none of the attention or criticism.

What we can do. None of this should be construed to suggest that white Christian nationalism is not a real and present danger to the United States. It is. And it should be treated as such. Fusions of politics and faith that place racial and religious identity as more important to national identity than peace and democratic norms should be identified and rooted out. And we can each do our part following the lead of Dallin H. Oaks and M. Russell Ballard. Under the broad creeping definitions above, it wouldn’t be at all surprising to see more and more people talk about all Latter-day Saints as falling under this damning label.

Amanda Tyler, the executive director of the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty wrote this summer, “I think Christians, who continue to make up a majority of Americans, have a special responsibility to step up at this critical moment to reject Christian nationalism.” She has also started an organization, Christians Against Christian Nationalism which takes measured steps to address Christian nationalism without slipping into secular nationalism.

If those of us who are Christians stand up for our Christian values and decry Christian nationalism, it can be particularly effective because it makes it clear that the problem is limited and extreme while also pushing back against efforts to broaden the phenomenon into a moral panic. We have the unique ability to fight the problem on both sides.

And we should work on developing a better approach to American identity. What ties each of us together is the onward pursuit of “liberty and justice for all.” Our founding set forward the audacious vision that we are all “created equal, that [we] are endowed by [our] Creator with certain unalienable rights.” This is a conception of the United States that is defined not by excluding people along racial or religious lines but by uniting all people who share that ambitious vision. That approach to our identity has the power to heal our divides and move us forward.