The world is teeming with voices of men and women who point people to light and truth. Joseph Smith acknowledged this in 1843 when he spoke of the value of entertaining strangers and sectarians. Promising them a listening ear, he said, “they shall have my pulpit all day.”

This ecumenical spirit is not only a gift to members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints from their founding prophet—it is also a gift (one of many) to a modern world fractured by partisanship and tribalism.

I was saddened by a recent Pew Research Center finding that most people fail a basic religious literacy test. This Pew survey presented respondents from various faiths with 32 fact-based, multiple-choice questions about Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, Sikhism, atheism and agnosticism.

“On average,” the report says, “Jews, atheists, agnostics and evangelical Protestants score highest on the new survey of religious knowledge, outperforming members of other Protestant traditions, Catholics, [Latter-day Saints] and Americans who describe their religion as ‘nothing in particular.’”

My people, the Latter-day Saints, answered 43 percent of questions correctly—a failing grade. To be fair, Latter-day Saints have performed better on similar tests in prior years. And, even Jews, who scored highest, averaged only 56 percent—also an F.

This Pew report, then, reaffirms what we learned as a nation during the 2016 election: We don’t know much about those who are not like us. If we socialize at all, we do so with those we already know. We are comfortable around like-minded people. If we are religious, it seems, we prefer to focus our attention solely on our own faith.

As strong as we are in so many other important areas, we are often unskilled as a people at listening to those to whom we are preaching.

This is an irony for Christians of all stripes, including Latter-day Saints. We are a missionary-minded people. We have a message that has blessed millions of lives and we believe it can bless billions more in unique ways. We take seriously the New Testament call of Christ to “make disciples of all nations.” Another portion of the Latter-day Saint canon, revealed to Joseph Smith in 1831, promotes proselytizing with equal force. Jesus told Latter-day Saints, “ye are not sent forth to be taught, but to teach the children of men the things which I have put into your hands” (emphasis mine). Latter-day Saints are well trained to evangelize the faith to anyone who will lend an ear.

But Pew seems to say (and my sliver of life experience in northern Utah confirms) that, as strong as we are in so many other important areas, we are often unskilled as a people at listening to those to whom we are preaching. Followers of Christ must ask themselves a hard question: How can we expect others to come worship with us, read our holy books, and turn their lives upside down for us if we aren’t willing to reciprocate?

One way to reconcile Jesus’s charge to teach and not be taught is to balance it with His other teachings. Elder Neal A. Maxwell (1926–2004) counseled Church educators to not “teach the scriptures in isolation from each other.” “In everything do to others as you would have them do to you,” Jesus says in the New Testament (and in slightly different language in the Book of Mormon). This is more than just a nice idea made for a Pinterest meme. Jesus doesn’t deal in banalities. “This is the law and the prophets,” Jesus (in my mind) emphatically adds. Yes, you have been given a pearl of great price that will bless the world in incalculable ways. But another key to bringing your brothers and sisters closer to Me and making the world one is your genuine interest in them as my children who have much to teach you.

I am as guilty as anyone in transgressing this commandment. Hindsight has helped me see how immature and prideful I was as a 19-year-old Latter-day Saint missionary in the former Soviet Union. On Easter Sunday, 2004, a cheerful 50-something woman in the eastern Ukraine city of Makiivka greeted me and others with the words, “Dear brothers and sisters, Christ is risen!” She was joyful and serious, and the group around us responded, almost in unison, “Indeed, He is risen!”

These Ukrainian Latter-day Saints were exchanging a Paschal greeting, an Easter custom they carried over from their Eastern Orthodox faith tradition. That night I wrote in my journal: “On Easter, the people here say ‘Иисус Воскрес’ [Jesus is risen] … in greetings, in testimonies, in talks, in lessons, saying goodbye. A little annoying.”

My lack of wonder as a Latter-day Saint Christian in response to the beautiful Easter tradition of another faith culture reflects an absence of interest in the people I was called to serve. Frankly, this was too common for me and other missionaries. Our passionate faith sometimes covered over our humility and blinded us to the goodness all around us. I wonder how many more people I could have helped had I gone slower, listened more intently, and observed more deeply what God was trying to teach me through those humble, hospitable people.

The Apostle Paul told the Saints in Corinth to be “imitators of me, as I am of Christ.” Had I known more about Joseph Smith when I was a missionary, I could have better imitated his Christlike largeness of soul, hospitality, and open-mindedness.

Those three traits were on display on a warm and rainy December evening in Portage County, Ohio in 1835. On that night, Joseph and a Baptist from a nearby town showed the world what it looks like to engage in constructive dialogue with a neighbor. John Hollister, a Closed Communion Baptist, visited Joseph to learn more about the faith tradition he helped restore five years prior. Hollister had heard “many reports of the worst character” about the Latter-day Saints and wanted to come see for himself if those accounts had any merit. The two talked all evening. Joseph found John to be candid and sincere, and even gave him a room to rest in for the night.

The next morning, after no doubt ruminating all night on what he had observed and heard the previous day, John shared a humbling insight with Joseph. Not only had his understanding of the Latter-day Saints changed—so too had his conception of religion generally. “Although he thought he knew something about religion he was now sensible that he new but little, which was the greatest, trait of wisdom that I could discover in him,” Joseph said. Three days later, John stopped by Joseph’s home to say goodbye. “[John] remarked that he had been in darkness all his days, but had now found the light and intended to obey it,” Joseph said.

Imagine that. A Baptist was blessed by what he learned from a Latter-day Saint. The Latter-day Saint is impressed by the Baptist’s deep wisdom and humility in the face of more information. Both, no doubt, were made better by the experience. Apply this today and replace “Baptist” and “Latter-day Saint” for the religious, social or political descriptor of your choice. Can you imagine the healing that would come if such dialogue happened in communities around the world?

Don’t you want more wisdom, more truth, more holiness, more friends who can help you think more deeply and more rigorously?

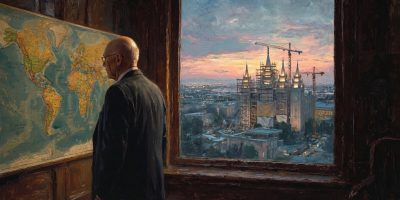

Happily, such dialogue is sprouting up around the world, across virtually every religious conflict that exists. For example, Jews and Palestinians have carried on vibrant dialogue for years outside of the limelight. And we have our own examples at the highest level of Latter-day Saint leadership. Just this year, President Russell M. Nelson visited Pope Francis at the Vatican, engaged in constructive dialogue with several Muslim leaders from New Zealand and Saudi Arabia, and welcomed the affable archbishop of New York to Temple Square. And that is only a sampling of his and his fellow apostles’ interfaith outreach.

In a Book of Mormon scripture, the Messiah asks, “Wherefore murmur ye, because that he shall receive more of my word?” Shifting the focus to religious literacy, I can imagine that same Savior saying, “What do you have against being more blessed by the diversity of my creation? Don’t you want more wisdom, more truth, more holiness, more friends who can help you think more deeply and more rigorously?” Truly, our God has placed us together on this planet to help and learn from each other.

Yes, they can learn from us. But we can also learn from them. “Be not forgetful to entertain strangers,” the letter to the Hebrews says, “for thereby some have entertained angels unawares.”

So let’s open up our metaphorical pulpits to one other, adopt both the welcoming spirit of Joseph Smith and the inquisitive nature of John Hollister, and bask in the grace of such angelic associations.