“Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself,”1 ranks as one of the most repeated verbatim command phrases in the Bible. We frequently forget, however, that this wisdom has two parts: loving our neighbors and loving ourselves. A central part of life’s journey includes finding a healthy balance or harmony between caring for ourselves (self-care) and engaging in acts of sacrifice to help others. For those who take their religion seriously, these choices often are often informed by their faith.

In a national study about the ways that families of various faiths live their religion, we explored how religious parents and youth cared for themselves and sacrificed for others. Many of those we interviewed reportedly struggled to figure out what combination of engaging in sacrifice and engaging in self-care worked best for them, their loved ones, and others. In their interviews, we identified four central themes that can help us understand how people of faith view and manage these behaviors. These themes included: (1) Motivations for Sacrifice and Self-Care, (2) Types of Sacrifice, (3) Types of Self-Care, and (4) Harmonizing Sacrifice and Self-Care.

Theme 1: Motivations for Sacrifice and Self-Care

Various motivations were identified as being important reasons for engaging in both sacrifice and self-care, including: personal, familial, and religious.

Personal motivations. David2, a Christian father, explained, “I was at a point where I realized I needed to be whole and complete and happy on my own and not dependent on anybody else for my happiness.” When discussing how selfishness was one of the biggest problems he and his wife dealt with, a father named Lyndon shared, “That’s probably what the biggest thing that we struggle with is just selfishness. I need time for me. She needs time for her.” His wife, Heidi, shared her motivation for participating in couple-based scripture study: “It is a time to be spiritually selfish and to fill up our bucket. Whenever I get frustrated or drained, at least I know we are gaining knowledge together.” Along with Lyndon and Heidi, other participants shared that it was sometimes appropriate to take time to be “selfish.”

Familial motivations. One example of self-care to meet the needs of her future family came from Jameela, an East Indian Muslim young adult woman:

I don’t want to prolong it too much, but I think the ideal age [to get married] would be after I finish up my schooling… . So I can be committed to a family, because a marriage and a family is such a big responsibility; I want to have as much of my attention that I can dedicate to my husband and ultimately my children.

Jameela demonstrated foresight as she shared how she thought about future relationships when deciding to take care of herself in the present.

Often, familial or relational motivations stemmed from a desire to make someone else happy or comfortable. Katrina, a Black Christian mother, said:

Whatever the need is, we do it all; we serve each other … whenever somebody has a baby or something, and we all just get together and serve them and make sure that her family has meals. Or she might be ill, or she needs to be hospitalized, or her husband may be out of work and have no support, whatever the need is. I mean, we all go to church, we all have each other, and I feel like … my husband and I … would be empty if we didn’t have that support from the church.

For Katrina, it seemed that her relational motivations to sacrifice stemmed from a desire to feel part of a community, to feel supported by others, and to provide similar support for others.

Participants often experienced meaning within their relationships when they engaged in acts of sacrifice. LeeAnn, a Catholic mother, explained how her religious beliefs encouraged and gave meaning to her motivations to sacrifice for family members:

[Jesus] came to teach us how to live as Christians and to live in love for each other, and I think that that really helps our family. Because of His sacrifice, sometimes maybe we might sacrifice an angry moment or something and keep it to ourselves and be kinder to each other.

Like LeeAnn, many participants suggested relational motivations that coincided with religious motivations.

Religious motivations. Calvin, a Black Baptist father, shared, “Part of … what we’re taught in our religion is giving of yourself.” Other participants appeared to share this perspective. Jimmy, an Episcopalian father, explained how his religious beliefs taught him to sacrifice: “Because I have to stand in front of God for what I did and did not do for my family … my job is to lift her burdens … so she can deal with the important stuff [like] raising kids.” Rozene, a Native American Christian mother, shared that she and her husband sacrificed because of what they felt God had told them to do:

We went to God-forsaken reservations across the United States. [I sometimes thought], This isn’t what I [was] raised for. Why am I here? What are we doing here? But … God sent us here for a reason, and I know that my husband provided much-needed care to these people, and we had roles even as young as we were.

Some of the religious motivations participants experienced came from religious teachings and beliefs, such as those shared by Jimmy, and others came from interpretations about reasons for life experiences, as Rozene shared.

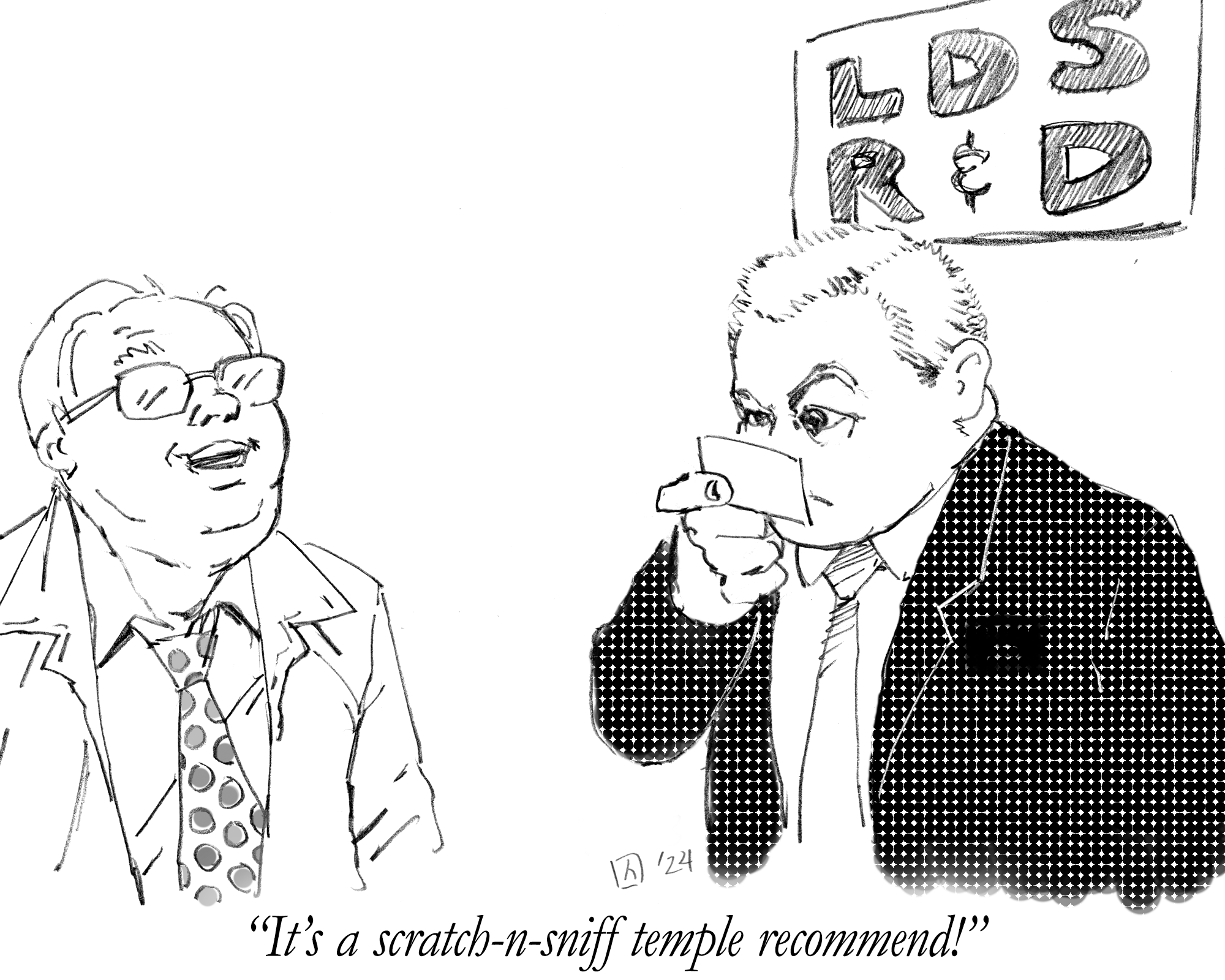

Several participants expressed excitement about spiritual self-care and sacrificing for members of their congregations. Benton, a Black, Latter-day Saint father, shared how he and other members of his congregation found joy in sacrificing for others: “Come spend a month with me at the church … [and] you’ll see a humble people, people [who] just really wanna work and do the things that the Lord has asked them to do, without pay.”

Theme 2: Types of Sacrifice

The types of sacrifice described in the interviews conducted included: food, time, school activities, social expectations, vacations, work, finances, and many others. Lee, a Christian father, shared how his family sacrificed where they lived for religious reasons.

The reasons we’ve moved so many times have been related to our work in the ministry … [we] sacrifice stability in terms of a long-term place… . We’d like, sometime, to have a place … that’s our place, so those have been sacrifices. Actually, when we moved here, we’d been in one place for a year, the kids were in public schools, and the girls especially were starting to form some friendships. That was a sacrifice to leave there and come here. I think they would say they’re glad that we’re here, and they’re glad for maybe the opportunities they have here now, but I think at first … it felt like a sacrifice.

Like Lee, several participants shared how one experience could hold multiple types of sacrifice for different members of the family.

Not all participants immediately saw benefits from engaging in sacrifice. Scott, a Catholic teenager, shared how he had to trust others to feel better about the sacrifices he made:

I’ve been the one known on my soccer teams that’s missed a lot of games. I lost lots of games over church or [Confraternity of Christian Doctrine; CCD]. And right then, I really hate it [and] I don’t want to go to church or CCD, but then I think [of] the people I’ve talked to: They actually say it’s going to be good for you, and I guess I kind of trust that.

Many of the teenagers shared that they sacrificed peer acceptance, sometimes through not participating in sporting activities when conflicting with religious observance, partying, or impulsive behaviors with their peers.

Theme 3: Types of Self-Care

Self-care was discussed in terms of physical, spiritual, social, and mental ways of caring for oneself. Rita, a black Christian mother, shared how she engaged in many types of self-care:

I ask God to direct me and show me what to do daily; sometimes, moment by moment, I ask Him to give me directions. I also have people that I call who are prayer partners who I ask them to pray for me, to pray for guidance. I spend time with my friends that I know are very supportive, and that I can talk with [and] I talk to my husband a lot during stressful times. I also exercise a lot.

For Rita, personal prayer, supportive church sisters, friends, her husband, and consistent exercise were all part of her varied approach to self-care. Indeed, several participants included the support of others (e.g., God, friends, family members) in their examples of engaging in self-care.

Abaan, an Arab-American Muslim father, shared some ways that he and his wife cared for their marriage: “Having common things that we do together is helpful for marriage. It could be religious practice, or it could be some hobbies that we have, that we can share.”

Many engaged in self-care when things became stressful or they realized something needed to change. When talking about how he tried to sustain several responsibilities unsuccessfully, Russell, a Catholic father, said, “We had to change our priorities. In life, you change your priorities according to what you can handle because you can go way overboard.” Manuela, a Latina Catholic mother, repeatedly fought to balance stress with spiritual self-care:

Spiritual time, which you do on your own, is not something that you say you’re going to do. [My husband] has a lot of time at work that he’s by himself, and so he has a lot more time to do that than I do. I’m at work with people all day. Employees ask me questions. I [sometimes] have to literally go hide, from children and him and the whole world, to be able to have any peace of mind.

We now move from the need “to literally go hide” to our final theme.

Theme 4: Harmonizing Sacrifice and Self-Care

When discussing connections between faith and family, many participants alluded to a struggle when deciding what was most important: caring for their own needs or others’ needs. Despite expressing the importance of sacrificing for others, many also shared thoughts and feelings about struggling with and resolving tensions between sacrifice and self-care. Abby, a Congregationalist mother, shared her struggle and resolution:

Of all the people I’m taking care of, I need to be included in that class of all the people who need their fair share of attention and time and love… . I used to operate from this perspective of … taking care of everybody else, but not seeing that I needed to be taken care of [was a mistake].

Abby shared that she was able to overcome her tendency to ignore self-care and now has found a better personal harmony between sacrifice and self-care.

Ubayd and Baseema, Arab-American Muslims, related the tension between sacrifice and self-care from a Muslim perspective. Ubayd stated, “There’s a saying in the Qur’an that says: ‘Take good care of your children.’” Baseema then added, “In the Qur’an, you have to take care of yourself first … but you are [also] responsible for your children.” Ubayd and Baseema were not the only participants who struggled with sacrifice and self-care in the context of their sacred texts and looked to religious beliefs, teachings, and doctrine to provide guidance. Anoki and Lulu, a Native American Methodist couple, reportedly cared for themselves by caring for others. Anoki shared, “I think we would agree [that caring for others] is an investment [for which] we are richly rewarded.” This led Lulu to share, “No matter what you do, a lot of times you think you’re doing it to help others, but you end up getting so much more for your time.”

As we continue the theme of harmonizing sacrifice and self-care, we turn to a married Korean Christian couple, the Choi family, who offered an account that, like Anoki and Lulu’s, features cheerfully-given service as a meaningful form of self-care.

Haesun (Wife): I enjoyed the church in San Diego much better than the one here.

Oui (Husband): She served a LOT. If someone was coming from Korea and she didn’t have a car or anything, usually my wife would help the person with riding and shopping and with all kinds of stuff …

Haesun: I had two Bible studies a week, and every Friday, I served my group dinner in my home.

Oui: 10-20 in the group, so it was not easy. We didn’t have enough money, but she liked it very much.

Haesun: …We did a lot together. Walks together on the beach. I was very happy there. They needed me, and I needed them.

Interviewer: You were happy serving others?

Haesun: Yes, they were happy, so I was happy. Here I [am not] needed [by] anybody. They are always busy with their job. I don’t have the friends, I don’t have the Bible study, I don’t have anybody [to] serve. …I am here alone.

In Haesun’s story, we see that sincere service rendered can be an optimal expression of self-care, while absence of service can result in isolation and loneliness.

For Jerome, an African Methodist father, it seemed that being able to find harmony between sacrifice and self-care was important. He said,

To reach out and love somebody, you gotta learn where you stand [and] be comfortable with where you’re at… . Then you can reach out and help someone else. Build on yourself; you gotta get that right first, then the other stuff will follow.

Desiree, an African Methodist mother, shared a specific example that seems to demonstrate the journey toward finding harmony between sacrifice and self-care:

We share our role so that whenever I’m not there or I’m frustrated, my husband takes over. So we’re complementary of each other, one can be stern, the other the comforter… . I’m with my kids all the time because I work at home. So sometimes, I get frustrated because I’m always here, and they’re always asking me questions. Because [my husband] works at night, he sleeps. Sometimes I get up to the hilt, and I have to call for reinforcement, backup, and I say, “I’m just leaving,” and he comes down. I come back thinking my house is going to be a wreck, and my house is clean, and my kids are clean, my kids are calmed down. So we just complement each other.

Eric, a Presbyterian teenager, shared a perspective that seemed to help him harmonize sacrifice and self-care when he said, “Hurting yourself is somewhat like hurting another person; taking care of your spirit is just as important as taking care of other people’s spirits.”

Conclusion

Through these accounts, we learn that people of many faiths have similar struggles, including finding ways to engage in sacrifice and self-care within family relationships in ways that lessen stress and provide for more positive experiences. In Western culture, people often use the term balance to refer to the process of struggling with these two types of behaviors that often seem to be at odds with each other. However, from the devoted women and men in the present study, we learn that it may not be that we need to engage in sacrifice and self-care in ways that make them “equal.” Perhaps it is more about discerning when it is appropriate to sacrifice and when it is appropriate to take care of oneself to harmonize sacrifice and self-care.

Many of the faithful individuals we interviewed reported that great blessings came through learning to wisely harmonize sacrifice and self-care in their lives—and that those blessings included greater love for themselves, their neighbors, and their God. They seemed to offer the collective message that the second great commandment, “Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself,” is loving wisdom from our Creator to engage in both sacrifice and self-care.

Notes

1. See Leviticus 19:18; Matt. 19:19; Matt. 22:39; Mark 12:31; Romans 13:9; James 2:8.

2. All participants’ names are pseudonyms.