Whatever else one might say about the love of God, it apparently does not demand the immediate end of suffering. Suffering is ubiquitous. Much of it seems pointless or unnecessary; much of it seems unfair. As we read in Job, “Man is born unto trouble, as the sparks fly upward” (5:7).

Some believers try to “save” God from the embarrassment of having created a world with so much suffering by downplaying the suffering that plainly exists. But this won’t do. Denying the depth of suffering is a way of looking away from the world God created. The pain of the world can’t be banished just by averting our eyes. Suffering persists, and sooner or later, just about everyone will face suffering that will not be silenced or ignored. Suffering disrupts our comfortable routines and shallow certainties.

Is all this human and divine suffering really necessary? There may not be a satisfactory answer to this question in this life. But it is possible to hazard a few guesses about why God might permit suffering to persist.

In what follows, I am not making the case “for suffering.” I’m not suggesting that we should “like” suffering or that we should seek it out. I’m also not saying that suffering always has an upside. I am suggesting that suffering can play an important role in our path towards God, and if it does, then our personal Via Dolorosa will not have been in vain.

One way that suffering can help us turn towards God is by humbling us and disabusing us of false beliefs. Suffering disrupts our comfortable routines and shallow certainties. In the depths of pain, we are forced to take a hard look at our lives to see what we are missing. We often find that we are not as virtuous, kind, faithful, or courageous as we thought we were. We find that we were going through the motions rather than loving God with all our heart, might, mind, and strength. God tries to speak to us in many ways, but when we are “past feeling” (1 Nephi 17:45), when we ignore the simple and profound ways that God tries to teach us, God is willing to use other means to get our attention. As C.S. Lewis says, pain is God’s “megaphone to rouse a deaf world.” In this space, there is an opening for us to turn towards God.

Pain forces us to look beyond the mundane and the trivial. In times of ease and comfort, it is easier for us to be bewitched by fleeting pleasures. But when true difficulty comes, we are drawn to look for what Blaise Pascal calls “a firmer way out.” In these circumstances, challenges and suffering are a gift from God to disburden us from false attachments. As one bible commentator writes, “And should we not consider all crosses, all things grievous to flesh and blood, as what they really are, as opportunities of embracing God’s will, at the expense of our own? And consequently, as so many steps by which we may advance in holiness?” Apparently, part of the price of having joy is knowing misery.

Pointing out that suffering is a precondition for joy might lead some readers to seek out suffering for its own sake, but this is not necessary. Like old age, suffering will find us whether we look for it or not. Further, the quest for righteous living will necessarily require us to face numerous difficult challenges. Jesus’ invitation to follow Him is upfront about the costs of discipleship: “If any man will come after me, let him deny himself, and take up his cross, and follow me” (Matt. 16:24, emphasis added). Loving fallen human beings is its own source of sorrow, as the example of our Heavenly Father shows (Moses 7:28-33). Apparently, part of the price of having joy is knowing misery. Paul As Bruce C. and Marie K. Hafen write, “The sorrows of our lives [can] carve and stretch … caverns … that] expand the soul’s capacity for joy.” Paul gloried in the tribulations that helped him know Christ better: “Therefore I take pleasure in infirmities, in reproaches, in necessities, in persecutions, in distresses for Christ’s sake: for when I am weak, then am I strong” (2 Corinthians 12:10).

Another way that suffering can work to our benefit is by making us deeper people. I don’t mean deeper in the sense of being intellectually deeper (though it may also include that), but existentially deeper. Through suffering, we become aware of the broader scope of possibilities of human existence.

We humans are generally creatures of comfort. We avoid or ignore the terrors that lurk just beyond a functional horizon of consciousness. Though we are dimly aware of just how bad things can get—especially when a friend or family member falls prey to some great injury or misfortune—we often suppress and downplay these possibilities, flattering ourselves that such things probably won’t happen to us. But then catastrophe arrives at our door, and we descend into the underbelly of pain and suffering that shatters whatever sense of normalcy we once had.

Down here, it’s deeply uncomfortable. No one wants to stay. But there is a sense in which we are more acquainted with reality here than when we are comfortable. Dross cannot endure the refiner’s fire. Jesus taught, “Every plant, which my heavenly Father hath not planted, shall be rooted up” (Matthew 15:13). Here we gain perspective on what matters most.

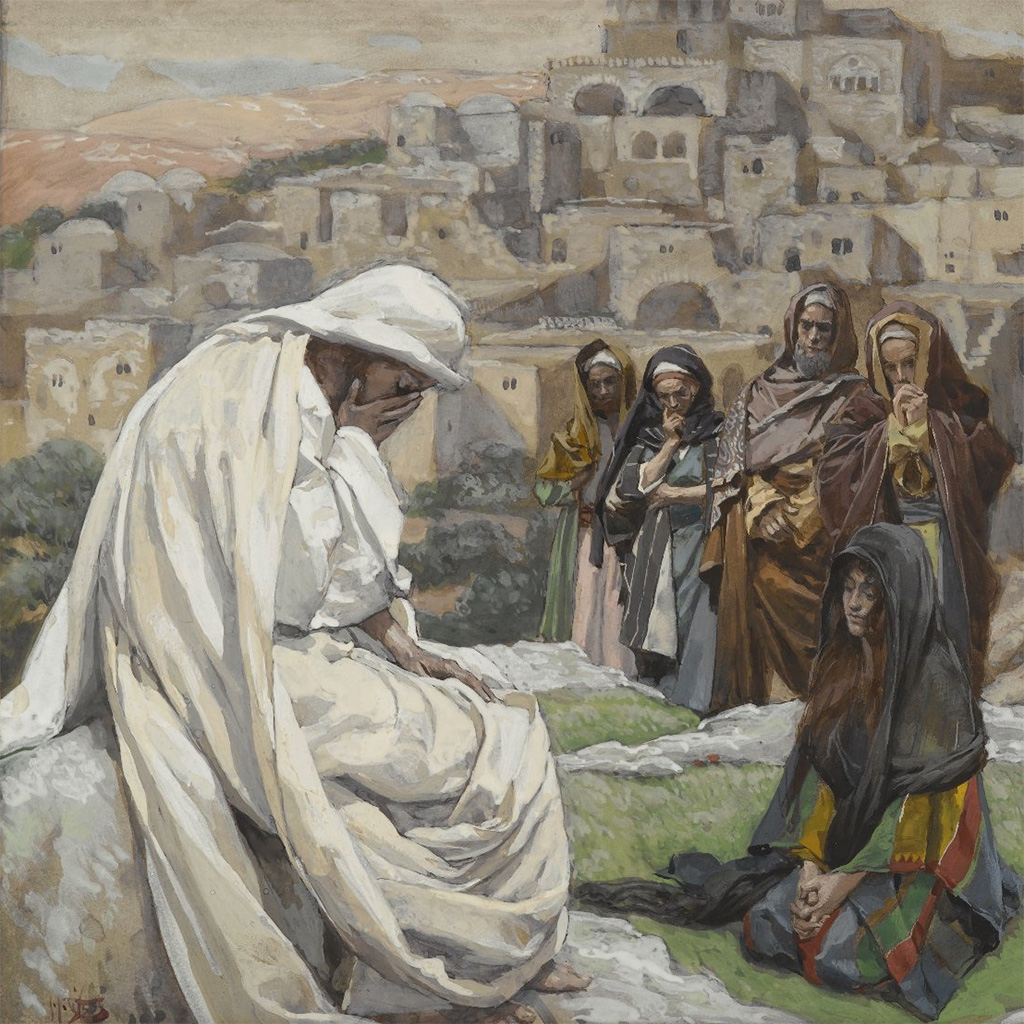

And, crucially, here we can find other people in a way that we cannot find them anywhere else. Everyone feels pain, and everyone wants their pain to matter. There is something deeply validating about having someone empathize with your pain, to feel it with you as you feel it yourself. When we pass through deep valleys of pain and suffering, we become capable of descending into those same valleys with other people, helping them face the terrors that seem overwhelming. According to Alma, part of the reason Jesus suffered all that He did was so that “his bowels may be filled with mercy, according to the flesh, that he may know according to the flesh how to succor his people according to their infirmities” (Alma 7:12). You never forget a friend who arrives and supports you in a moment of extremity. Everyone feels pain, and everyone wants their pain to matter.

When we tell the story of Easter, we rightly focus on the resurrection of Christ and the empty tomb, for joy and redemption have the last word. But that joy wouldn’t be what it is without the terrible price Jesus paid to achieve it. As Elder Dieter F. Uchtdorf recently taught, “We tend to think of joy as the absence of sorrow … But what if joy and sorrow can coexist? What if they have to coexist?” Suffering prepares us for the joy Jesus won at such a high cost.