Beyond offenders, research points to enabling conditions that make abuse easier to commit and hide.

We’ve mastered cynicism about marriage; it’s time to recover the drama of reconciliation.

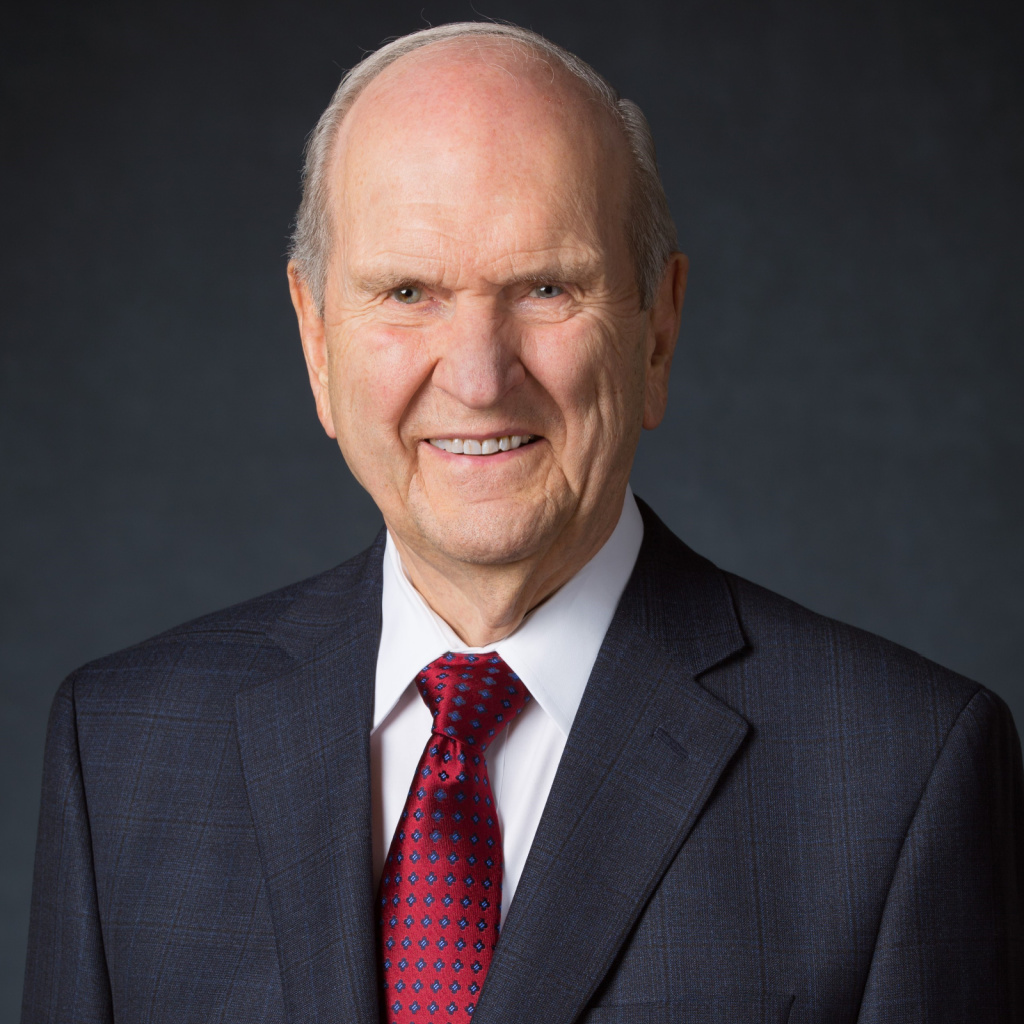

Who is Clark Gilbert, the newest apostle called to join the Quorum of the Twelve of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints?

Drawing your attention to this piece published yesterday in the New Yorker, “Our Obsession with Ancestry Has Some Twisted Roots.” The article has some interesting insights but ultimately tries to paint the Church of Jesus Christ’s influential role in genealogical work as somehow “twisted” as the title implies. The article has much larger targets than the Church, but it unfortunately demonstrates how casually some journalists subscribe to centuries-old tropes casting Latter-day Saints as somehow sinister.

Despite the appearance of a sharp competition between coherent ideologies, could it be that America is divided by group loyalties and resentments more than anything else?

A new letter from the First Presidency has opened up many conversations about the reasons and universality of following prophetic counsel. But prophetic counsel is meaningful because it can stretch us in new and unexpected ways.

Over the centuries, the Catholic Church had evolved from non-violence to a “just war” doctrine. Dorothy Day responded with a new pacifist theology.

Stay up to date on the intersection of faith in the public square.