Recently, I sat in Sunday School at my local meetinghouse and found my interest piqued by a member’s comment. The member referenced a psychological study, popularly known as the Marshmallow Test, to reinforce a point the teacher was making about how resisting temptation in this life will reap much larger rewards in the next life. The member mostly accurately described the gist of the study. A child was given a single treat and then was told that if they could wait 15 minutes before eating it, they would be given a second treat. The member reported that the children who could delay their gratification manifested a number of beneficial life outcomes as adults compared to those who could not hold out for 15 minutes. The instructor thanked the member for the comment, noted how well it suited the point, drew several direct parallels to God’s way of working with us, and then moved on with the lesson.

Normally, that would have been the end of it. Members often reference social science theories and studies like the Marshmallow Test in church classes, and folks generally find the studies to be interesting, evidentiary, and basically compatible with the gospel and God’s purposes. However, on that day, I was sitting there, a social psychologist and someone very familiar with the original study, as well as several replications of that study conducted more recently. Unlike most members, I am acutely aware of a significant concern with the lack of diversity in the sample of children Mischel studied. I also know that the predictability of life outcomes over time decreased dramatically in replications when a more representative and larger sample was used and when researchers controlled for characteristics of family and environment.

I am also familiar with the studies of hunger and starvation conducted by Jewish physicians in the Warsaw Ghetto in 1942 and then more systematically by Ancel Keys and colleagues at the University of Minnesota. I also know from my decades of research on the Holocaust about the horrific effects of hunger on concentration camp inmates, including a father who, to his own horror, stole bread from his son. I know of hunger’s long-term impact on survivors, some of whom had to keep their pantry full of bread for the rest of their lives.

As these thoughts passed through my mind that day, my hand reflexively went up, and I found myself contextualizing the study for the class, noting its potential biases, and giving a short polemic on judging the actions of people, especially children, who may have known significant deprivation and even starvation in their lives. I did not want to give this correction. I did not want to speak at all. I did not want to be judged myself, perhaps as a know-it-all, the arrogant professor, or worse, the sometimes-presumed stereotype of the higher education indoctrinator! I did not want any of it, but when things just are not being presented fully and correctly, and you are the person in the room with the expertise to know that, what do you do? Do you just let it go? Do you let people draw mistaken and unreasonable conclusions because a member’s comment seems to have the imprimatur of empirical science behind it?

If I was a CPA and someone made a misleading comment in a Sunday School class about modern tax law in relation to the verse about rendering unto Caeser that which is Caeser’s that needed context and correction, wouldn’t members want me to say something? It might save them from committing an error on their next tax return, getting audited, or worse. Don’t we need experts, even in our Sunday School classes, to help us navigate all the information that is out there in the world on every topic and idea? Aren’t the voices of people who can help us understand and see things more clearly and accurately critically important?

A Psychological Age

I would like to think that we would all say yes. However, we live in a time when psychological terms and concepts saturate our culture. Everyone knows them and is increasingly comfortable bandying them about with an air of expertise (The same is definitely not true of tax law!). If you want to test my point, just listen in on your kids’ conversations with their friends some time. You will hear a lot of psychology-speak. I know because when these kids come into my office for an initial therapy session, they immediately and confidently provide me with all their self-identifiers and diagnoses:

I am asexual, polyromantic, and ADHD. I manifest symptoms of scrupulosity, and I have some Bipolar 1 tendencies. I also have PTSD from early childhood trauma. I am looking for a cognitive-behavioral therapist, ideally one with expertise in EMDR, to help me work through these things in coordination with my Psychiatrist, who prescribes meds for my chemical imbalances. Can you help me with that?

And the kid is 14 years old! There is little depth of understanding and almost no bona fide expertise.

The problem is, just as it was with the member’s comment in Sunday school, that for all of this confidence and comfort in citing psychological terms, theories, studies, and disorders, there is little depth of understanding and almost no bona fide expertise. As in so many domains these days, there is an abundance of information about psychology available from a seemingly infinite number of sources. However, absent a modicum of informational literacy, some basic scientific and critical thinking skills, and, for church members, an awareness of how the psychological and the spiritual can and should be related to one another, there is a real risk that people will contract “Veneereal” Disease.

Veneereal Disease

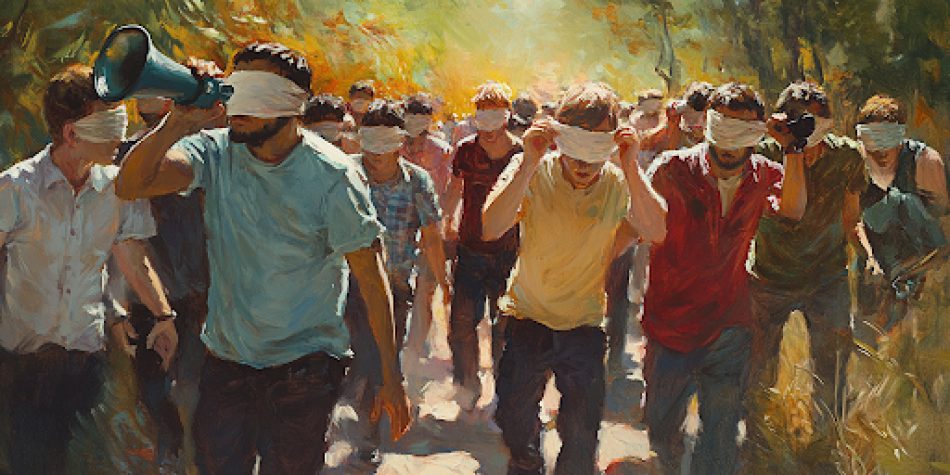

Veneereal Disease, as I have labeled it, is a risk of a kind of infection that is associated with information promiscuity. Information promiscuity essentially means having indiscriminate information intercourse with whatever search engine or social media outlet or news program one encounters or frequents. In the context of psychology, we can also include self-help books and all manner of spokespersons for psychology who show up regularly on a screen of some kind. The problem is that with indiscriminate information intercourse, like indiscriminate sexual intercourse, we may encounter “clean” or good sources of information as we go from source to source, but it is also possible that we will come across “infected” or bad sources of information as well. And, because we lack expertise and depth of knowledge, we won’t know the difference between clean and infected information. It is all presented as authoritative and true. We can be like the dogs Christ spoke of in Matthew, who are not to be given holy meat because they cannot distinguish it from unholy meat. It’s all just meat for them to eat that satiates their appetite.

Symptoms

Veneereal disease’s chief symptom is having a thin veneer of knowledge that is inevitably a mixture of undifferentiated good and bad information, which is just enough to make us dangerous, as we might say. Despite having only this surface-level mix of good and bad understanding, people infected with veneereal disease often express the added symptom of high confidence in the accuracy of their knowledge, much higher confidence than is warranted. This confidence leads the infected to see themselves as a source of information and to spread their veneer of understanding with an air of expertise.

I see these symptoms on the rise in my psychology classes, where students share their personal understanding of a topic or concept as if it is as valid as psychological theorizing and research. I initially thought these students just had not studied the material and were unprepared, but now I see that it is something different. They appear to have come across relevant information at some point, and they believe that the information they have gathered from whatever hearsay, social media, and AI sources they may have encountered is fully on par with the content of the course textbook and my course lectures. Indeed, some will share their own “research” and thoughts on the matter, even when I ask them directly to base their answers on psychological theory and research covered by the book. When they get a low test grade, they are legitimately surprised and complain. They ask me to explain how they got the questions wrong when they felt really good about their answers. When I tell them that their answers made no direct contact with the content of the course, they remain incredulous.

Susceptibilities

If the chief symptom of veneereal disease is high confidence and low accuracy in superficial and undifferentiated information, its chief susceptibility would have to be the cognitive and ethical miser. The term ‘cognitive miser’ is used by social psychologists to describe a common tendency to withhold cognitive energy and effort, relying instead on rules of thumb, first impressions, and stereotypes that require less mental exertion. I use the term ‘ethical miser’ to describe a similar tendency to withhold the moral energy and effort needed to encounter and treat others as human beings to be met and related to rather than objects to be used.

A classic illustration of both the cognitive and the ethical miser is what often happens when we come across an apparently houseless person on the street holding out a cup and asking for money. If we are in a hurry, we might not even notice them, and if we do notice them, we will likely stereotype them in some way. If we lack the ability to determine what their circumstances really are and whether what they are asking for is what they really need, then we will likely rely on our assumptions and rules of thumb about giving money to people who beg for it. If we are not intending to be helpful to others at that time but are motivated toward some other goal, that other goal will occupy our thoughts and we will likely pass by the beggar with very little thought or attention to their needs. In all of this, we can objectify and even dehumanize the beggar. We might even block our vision of these people with our hands so we do not have to see and feel their humanity, so we can avoid their faces and the pull of their apparent depravity upon us.

Being a cognitive and/or ethical miser not only happens on the street. It happens on computer and phone screens all the time as we scroll rapidly through our feeds, only mildly motivated, if at all, and lacking any ability to discern anything behind what we see. As we scroll, we make snap judgments about the people and the information being provided, signaling our approval or disapproval with a gladiatorial-like thumbs up or thumbs down emoji, or a left or right swipe, and all the while relying on algorithms to do most of our thinking for us. We do not see the human face of others but only images, idols, and facades that promote objectification and dehumanization. We are not exposed to hard-earned wisdom and tested knowledge, but only soundbites and clickbait traces of seemingly significant information. We are not exposed to hard-earned wisdom and tested knowledge.

The Cure

With the risk of infection high and the spread of veneereal disease on the rise, we might wonder whether there is a cure for this social illness. The treatment regimen that promises the greatest success is discernment. I say treatment regimen because discernment is a practice that requires ongoing attention, effort, and development. It is not a quick-fix pill. It also is not a solo project. It requires community, both vertically and horizontally, meaning we need guidance and counsel from experts above us and alongside us.

Humility

A full discourse on discernment is not possible here, so I will focus instead on a few key practices that can help develop this cure for veneereal disease. The first practice is to admit our tendencies toward being a cognitive/ethical miser and remind ourselves that we often rely upon initial impressions, clickbait, short-shrift news encapsulations, hearsay, trust in authorities, rules of thumb, and stereotypes that can objectify and dehumanize others. We can acknowledge that we are sometimes unwilling to expend the effort and take the time to be the most thorough and moral consumers of information, and, therefore, we are also not always the best distinguishers of good and bad information.

To discern just this one truth would have a much-needed curative impact on veneereal disease. It would promote humility and the practice of a healthy skepticism of our own ideas. We would hold information tentatively and be open to surprise. We would still commit cognitive and ethical errors with the information we consume, but we would know that we are prone to error and that awareness would perhaps give us pause before we post a political statement online, share a psychological study in Sunday school as scientific fact, or diagnose ourselves with a disorder. It might lead us to choose our words more carefully, perhaps even to preface our claims with something like, “I am not an expert on this topic, and I have not examined all sides of the issue fully, so please take what I am about to say with a grain of salt.” As our humility increases, our confidence will better match the level and quality of our knowledge.

Critical Thinking

The second practice is to expend more cognitive and ethical energy in deeply processing and critically thinking about the information we encounter. In a book on critical thinking about psychology, my co-editors and I discuss the labor critical thinking requires and the value of investing more effort in that labor. By carefully examining the assumptions embedded in the information we encounter, tracing those assumptions to their implications or consequences for human beings, and then also considering alternative assumptions and their implications, we can achieve a deep understanding of information, and we can make an informed decision about whether we should consume it and share it with others.

Mischel’s Marshmallow test, for example, includes assumptions about motivation and reward, the relationship of one’s childhood self to their adult self, free will, the capacity for change, and the scientific method’s feasibility in studying human consciousness. Each of those assumptions has important implications for how we raise and educate children, view them in relation to their environment and socio-economic status, intervene to affect change, and so on. Finally, there are alternative assumptions about these things, some of which are found in scripture, including non-reward-based motivation, environmental and experiential constraints on agency, the possibility of discontinuous change and even transformation, and qualitative methods of investigation, each with different implications for how we understand and treat each other around things like hunger, gratification, temptation, and more.

Learn by Faith

Finally, we can practice learning by study and by faith, not as two distinct practices but as an integrated activity in which we examine and ponder information with a sincere and abiding intention to discern its quality and value by the light of Christ. Because the light of Christ “fills the immensity of space,” it is “in all and through all things” and “giveth life to all things.” Thus, it is between us and our computer and phone screens, present in our conversations and debates, and inhabits our congregations. It can enter our eyes and our ears along with the information we see and read and watch and listen to.

If we have eyes to see and ears to hear, Christ’s light will enter and illuminate our whole being and will purge us of bad information. We will understand, be edified, and rejoice together. We will not be like dogs indiscriminately consuming all that is placed before us. We will learn to discern our own susceptibilities to veneereal disease. We will minimize its symptoms by not leaning on our own understanding but yielding to His wisdom as it comes through inspiration and trustworthy experts. We will be cured of and inoculated against veneereal disease by the practices of humility, effortful critical thinking, and seeking wisdom in faithfulness to the Savior out of the best books in whatever form they may take in these technologically heightened days. We will enjoy a clean bill of informational health and wellness, and we will not spread veneereal disease to others.