What is Conflict?

How would you define the word Conflict? What does conflict look like? What does conflict feel like? Taking only 1 minute to complete the following statements right now––before reading the rest of this article––will help avoid bias, creating a valuable opportunity for personal insight.

Conflict is . . .

Conflict looks like . . .

Conflict feels like . . .

Here, conflict is defined as when two or more opposing forces meet each other. But don’t toss out your definition yet. Understanding visual or verbal analogies used when describing the word can grant insight into an individual’s intrapersonal relationship with conflict. Positive and negative conflict associations equally have pros and cons. Adopting a “conflict is natural” perspective––which is neither positive nor negative––leads to highly productive conflict resolution. Understanding one’s current perspective of conflict and maturing it toward a “conflict is natural” perspective can help Christian disciples answer the call of “Peacemakers Needed.” Positive and negative conflict associations equally have pros and cons.

Conflict Associations

The video begins with a Rorschach-inspired inkblot. The seemingly random yet iconic inkblots of the Rorschach Test take root in Jung’s Word Association Test and Freud’s Free Association Technique. Each of the psychology practices endeavors to bridge the mystery of subconscious associations for conscious observation. For example, answers given to the statements at the beginning of the article can create the opportunity for the conscious self to observe subconscious associations with conflict. When exploring definitions, analogies, or sensations associated with conflict, consider the positive or negative nature of those associations.

Negative associations typically characterize conflict as something repulsive or violent and to be avoided or discouraged. Examples from the video include rhinos charging each other, or the Earth covered and blown apart by explosions. One might picture two people verbally or physically fighting. Typically these scenarios have high or tense energy, but may also include feelings of isolation or fear motivating avoidance. If answers reveal a conflict perspective with negative associations this could be a good thing or a bad thing depending on the circumstance. These individuals are unlikely to engage in unnecessary conflict and make a significant effort to avoid negative outcomes when in a conflict. Sometimes, however, negative associations can lead people to shy away from necessary or productive conflicts, leading to hiding, isolation, or stagnation. For these people it’s important to remember not all conflicts end in pain, suffering, or destruction. Constructive conflict management can lead to peace, growth, and prosperity. Conflict is commonly associated with contention. In many cases, they are treated as synonyms.

For Latter-day Saints, conflict is commonly associated with contention. In many cases, they are treated as synonyms. Having frequently facilitated discussions with Latter-day Saints regarding the theory of conflict management in educational and religious contexts, nearly every discussion includes the misquoted scripture “Contention is of the devil” (3 Nephi 11:29)––typifying a negative association. If any of them had a childhood like I did, they were probably repeatedly quoted that principle by a parent frustrated with their children’s bickering. And fair enough, the train of thought for this association is easy enough to follow:

The Devil is bad––Contention is of the Devil––Contention is bad––Contention comes from conflict––Conflict is bad.

This Transitive or Association Fallacy informs poor conflict management behavior typical of negative associations:

Shun the Devil––Contention is of the Devil––Shun Contention––Contention comes from conflict––Shun conflict.

This paragraph could continue into its own article, and a future article will discuss the pros and cons of avoiding conflict and why it isn’t a one-size-fits-all conflict style. For now, it’s probably enough to point out that contention and conflict are not the same thing in Latter-day Saint doctrine (see TG Conflict versus TG Contention). Conflict is when two or more opposing forces meet each other. Contention comes from trying to resolve a conflict while motivated by anger. While all contention comes from conflict, not all conflict leads to contention. While all contention comes from conflict, not all conflict leads to contention.

The Farmer and His Horse

Indulge a Chinese fable first whispered to me in the backstage of a small theater several years ago by an older friend offering me perspective during a hard time. I was excited to hear the same story from Elder Garret W. Gong in his recent talk, All Things For Our Good. Just like all good fables, there may be differences in their telling and multitudes of meaningful interpretations. While trying to avoid forcing my take-away on you, I share the version as it was first told to me.

A farmer who lives on the frontier loses his horse to the wild.

His neighbors offer condolences.

While his father says, We’ll see.

The horse returns to the farmer, bringing with it a herd of horses.

The neighbors congratulate his fortune.

While his father says, We’ll see.

The farmer breaks his leg while riding a new horse.

His neighbors offer condolences.

While his father says, We’ll see.

War breaks out on the frontier.

The army does not recruit the farmer because his leg is broken.

The neighbors congratulate his fortune.

While his father says, We’ll see.

A Nature-al Perspective

A meditation of conflict associations may reveal a positive or negative subconscious bias. But there is a more productive conflict perspective. Conflict (just like rain, a natural phenomenon) can be thought of as either positive (like when a farmer needs more water) or negative (like when an outdoor dinner party gets rained on). However, consider how the management of the conflict can also be thought of as either negative (if the farmer drinks and gambles away his surplus profit) or positive (if the dinner guests dash inside and cozy up next to a fire). Consider these other analogies for conflicts observed in nature as used in the video;

- The biological differences of Male and Female

- Wood fueling a campfire

- The earth’s relationship with both the sun and the moon

- A wave washing up on a shore

Nature is full of conflict, yet it is neither positive nor negative. Conflict is just like nature; it is not the source of our positive or negative associations. “There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so” (Shakespeare in Hamlet 2.2). Conflict is neither negative nor positive: conflict is natural. When adopting this perspective, instead of the conflict being positive or negative, it is our response to conflict––also known as conflict management––which becomes either poor (negative) or productive (positive).

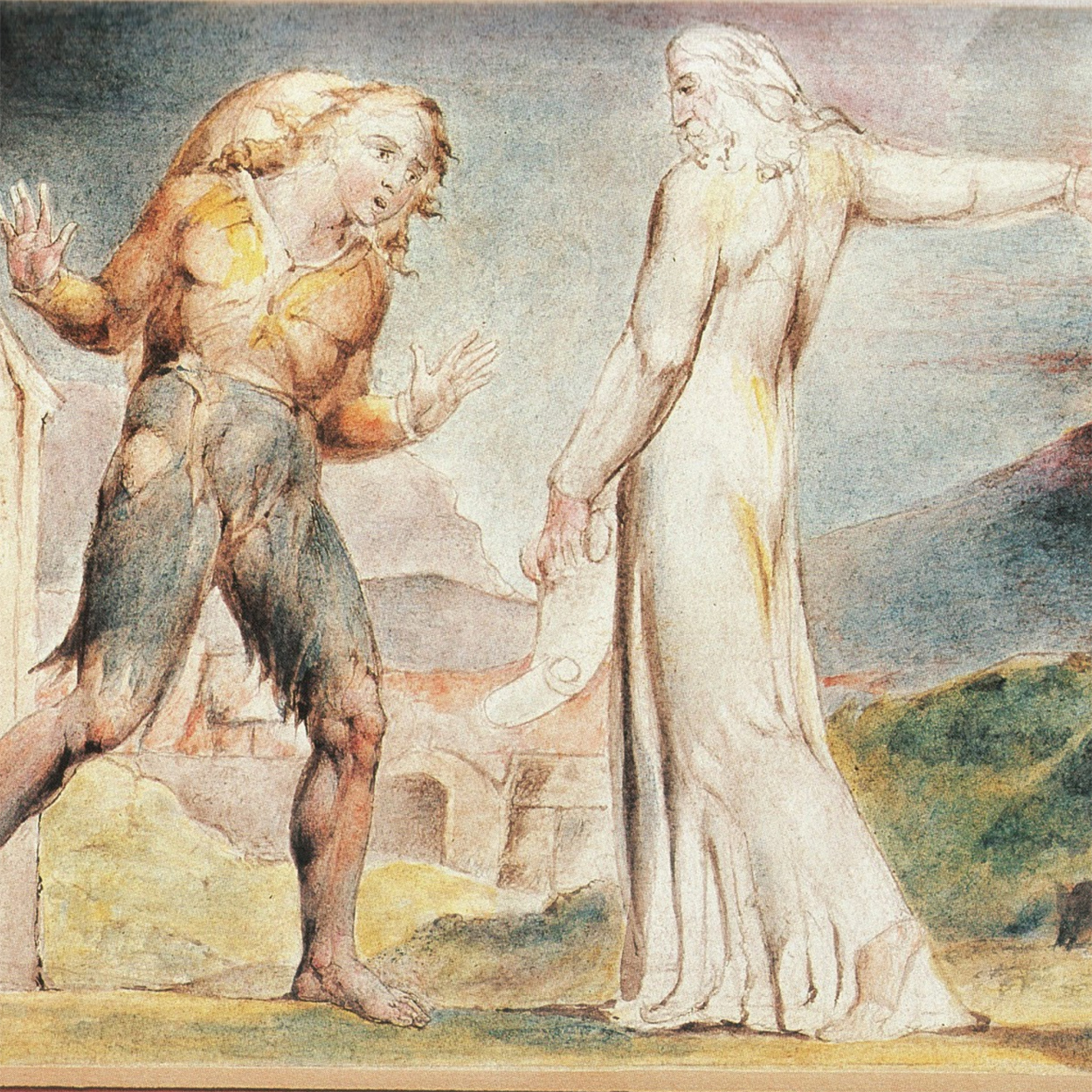

A Christian Application of the “Conflict Is Natural” Perspective

The Taijitu is a powerful symbol of the Eastern philosophy of Yin and Yang. It communicates at once both conflict and harmony and the reciprocal dependence of conflict upon harmony and harmony upon conflict; neither exists without the other. In a similar way, the Cross is a symbol of both suffering and exaltation and their mutual dependence; neither exists without the other. While both symbols have vastly more complex associations than these gross reductions, they may serve as effective visual analogies for the fundamental Latter-day Saint doctrine: “It must needs be that there is an opposition in all things” (2 Nephi 2:11). Individual agency is enabled through opposition (2 Nephi 2:16). As linked before, Conflict in the Topical Guide only refers to two other words: Opposition and Problem-Solving. “The Savior’s message is clear: His true disciples build, lift, encourage, persuade, and inspire—no matter how difficult the situation. True disciples of Jesus Christ are peacemakers” (President Russel M. Nelson). Letting go of negative or positive bias and embracing a ‘conflict is natural’ perspective enables peacemakers in productive conflict management by reinforcing individual agency.

Want more?

Check out and share all 12 videos from the Peacemaking Series, now available on YouTube, or read similar research, videos, and podcasts at thefamilyproclamation.org. Return to Public Square monthly for more articles expanding on the theories used to create each video.