As my son and I sat watching The Mission, a Robert De Niro, Jeremy Irons film with a stunning Ennio Morricone soundtrack, I commented that the name of the film could be changed and improved to “Guarani Lives Matter.” It tells the story of the Catholic-Church-sanctioned Spanish and Portuguese conquest of Brazil and their opposition: the indigenous Guarani allied with a handful of Jesuit priests.

It occurred to me that “______ Lives Matter” could be a rallying call throughout history—with only a few brief respites during general peace.

All of the conditions that lead to calls of “______ Lives Matter” have one thing in common: enmity.

The Establishment of Enmity

Years ago I attended a class that would have allowed me to carry a concealed firearm. The instructor, a former Marine, made it clear that when it came to taking a life, even in self-defense, the only way to emerge from the situation with any psychological normalcy would be to categorize the dead person at my feet as an animal and not human at all.

This suggestion shows the universal necessity, usually implicit, of value stratification when harm is to be inflicted on another human. Value stratification is the practice of placing classifications of humans into a value hierarchy. The concealed carry instructor had suggested an explicit, psychological value stratification, one that placed my life and the lives of my family members as not only more valuable than the life of the person I might kill in self-defense, but as superior as a human is to an animal. There cannot be enmity without stratification. Enmity is the categorization of other humans as inferior to ourselves and therefore worthy of mistreatment.

So it was with the Spanish and Portuguese and their stratification that placed themselves above the Guarani. So it was with slave traders, slave owners, and everyone not involved in the rescue and release of slaves from the time the first Europeans landed on America’s shores to today. So it was with the conquest of the United States and the subjugation of Native American populations, so it was with Nazi’s, and so it still is today.

Some stratifications are more insidious than others. Slavery is worse than a lack of suffrage. Yet the difference between the ranking of a black slave in the southern United States a century and a half ago and a woman prior to suffrage is one of degree and not of kind.

Whatever other progress has taken place, overall progress has been slow and piecemeal. And our current time seems to have done little to address the broader and more permanent issue of enmity. Perhaps that’s why the conflict over race has seemed to only grow more intense in our day.

Enmity for the Sake of War

War demonstrates enmity in all its horrific purity. One could argue it took the enmity of politicians on the American side to send young men mostly from among America’s working class to fight a foolhardy war in Vietnam. The implicit, elitism-laden, value stratification of such politicians took the form of the determination of expendability for the sake of misguided interventionism. I’m not the only one to conclude that the American ruling class regarded thousands of working-class young men with enmity, treating them as expendable tools for geopolitical aims.

The enmity-justified elitism in President Lyndon Johnson, who put two feet on the war accelerator, was demonstrated in multiple ways. His insistence on placing himself as the top, most valuable human on the planet is at least partially captured in the following incident: Once Johnson landed at an Air Force base and a young officer directed the President over to a helicopter while saying, “Sir, your helicopter is over here.” Johnson replied, “Son, they’re all my helicopters.”

Then there was the hideous behavior of soldiers themselves. To make killing thinkable, the American soldiers needed to dehumanize Vietnamese soldiers and civilians, labeling them as “gooks” (just as Germans were “krauts” and Japanese were “japs” during WWII). This act of enmity lessened the certain and devastating psychological self-harm over taking the life of a valuable other. This is also true of Vietnamese soldiers and the dehumanization of Americans. On the homefront, Vietnam vets came home to a hostile public who called them “baby killers,” further adding to the overall enmity of war. Of note, is that war enmity does not always occur as racism. Enmity is a much larger set.

The horrific loss of life, treasure, innocence, family, and happiness had no gain that I can calculate (with the possible exception of some of the greatest protest rock and roll ever created). Enmity is caused by and causes war in an ever-widening, vicious circle—no matter the elaborate justifications each side comes up with to justify its own contempt. Violence creates hatred and hatred spawns violence.

Fears of widening conflict and violence in America exist now on both sides of the political spectrum.

Inevitable Outcomes of Enmity

On May 25th at about 8:15 in the evening in Minneapolis, Officer Derek Chauvin’s human value stratification resulted in the killing of George Floyd. This murder is a microcosm of a much larger value stratification in America.

It seems that our inherited, intellectual propensity to categorize things in the world has been so successful, that there is a tendency to apply categories to people. This leads to human taxonomies that include value and morality. As humans are valued as being less valuable and perhaps, evil (enmity), there is a justification for mistreatment. Once categorization becomes rooted as part of a larger social system, it is difficult to question its validity unless there is some seismic shift. Derek Chauvin is not responsible for the creation of his largely inherited categorization. He is responsible, however, for both his contribution to its calcification broadly and his acting it out individually.

Especially for Americans, system-bucking is considered high virtue. It is, after all, what the founders of the nation did. The Thomas Jefferson quote, “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” is system-bucking at its finest, though poorly acted out by Jefferson and his fellow founders. Some moral credit among the founders is deserved, especially when judged against the moral/racial ethic of the time. Slavery was abhorrent to many of the founders who eventually gave in as a compromise only in order to bring the south into the union.

The problem for some early leaders, including Jefferson, was how exactly “men” was defined. In this case, he really meant just men (not women) and land-owning white men at that. The statement taken in its nominal purity is noble for sure. The execution of the same was certainly an improvement over the practices of time immemorial. Jefferson’s proclamation would deserve an A if graded on a curve for the time, but it earns no better than a low D on an absolute scale due to how it was applied.

Religion

The outcomes of religion, especially Christianity, should, if followed, result in peaceful, egalitarian practices and societies—but so often fall short. Perhaps too much is expected. Christian humans are also Greek, American, Latino, African, republican, humanist, libertarian humans who inherit societal baggage frequently based on enmity. Said another way, Christians frequently let their religion filter through their political or group ideology resulting in a convoluted worldview that would be barely recognizable to Jesus. Within a century of His death, Christianity became a social structure, a political ideology, a coded language. Jesus tried to separate His teachings from the domain of Caesar, but this division didn’t last long.

How do people espousing the Christian religion produce the Crusades? How do two Christian religions war with each other for decades in Northern Ireland? The list of agonizing atrocities somehow associated with people of faith is long. In the movie The Mission, the Jesuits were the Christians who acted out Jesus’ and Paul’s admonition toward egalitarian and even sacrificial outcomes. The far more numerous “Christians” like the conquistadores should hardly be called by that name if their actions were the measure of their Christianity.

But there were Jesuits and those like them, then and now, who refused to let their religion be deformed by their sociopolitics and thereby refused enmity.

My own religion is no exception. We are made up of multiple ideologies and nationalities along with our various associated, non-Christian baggage. Too often, we also let our religion inadvertently become skewed and misshapen from the influence of our sociopolitical inheritance—something that shows up painfully in our own history. This is both an embarrassment and a recognition of typical human reality.

At first glance, even the Book of Mormon suggests some value stratification although this certainly does not bear out when the message of the book is taken in its entirety. The Nephites were, as in the Old Testament, told by God to be endogamous for a time (marriage within a specific group as required by custom or law), going so far as to identify outsiders by skin tone in a way that is challenging to modern readers (2 Nephi 5:21). The overriding and predominant message, however, is toward at least equity and in its perfect state, equality.

The champions of champions (Alma and the sons of Mosiah) in the book were those who loved the lives of those outside the group with whom they identified at least as much as they loved their own. Jesus’ own actions in the New Testament towards “outsiders,” and the giving of his life for all—embody the quintessential example of this. And perhaps predictably, the Book of Mormon’s culminating event—Jesus’ visit to the American Continent—in the battle between enmity and equity, ushered in a complete and remarkable dissolution of human value stratification and therefore, enmity.

“There were no robbers, nor murderers, neither were there Lamanites, nor any manner of -ites; but they were in one, the children of Christ, and heirs to the kingdom of God” (4 Nephi 1:17).

Certainly, for members of The Church of Jesus Christ, taking cues from the Book of Mormon will necessitate a decrease of enmity until it reaches zero, along with a stronger sense of egalitarianism and self-sacrifice.

Christianity is surely not the only religion to sometimes suffer from elitism. Any time there is a claim, valid or not, that one group is the chosen people, the human tendency is to create a value stratification with “us” on top and all of “them” below.

Indeed, this is no doubt true of all human communities. Among non-religious, professional, academic, and other groups, elitism, and therefore enmity, is ubiquitous. But with these, there is no available counter-balancing call to a higher standard as there is with the teachings of Jesus and other spiritual leaders.

Systemic and Individual Influences

Since the killing of George Floyd, there has been as strong a call for structural change as I have ever seen. One of the evidences of the strength of this call is the change in attitude regarding Colin Kaepernick. When Kaepernick first took a knee during the national anthem at an NFL football game, he was vilified to the point that there were calls for NFL boycotts—with the football league administration only tepidly supportive. Today, even Nascar, a bastion of conservative, southern whiteness, has banned the Confederate flag from its events. Kaepernick’s social currency value has swelled to the point that he is receiving praise from sports personalities like Brett Favre, Pete Carroll, Megan Rapinoe, and others for both his statement and the way he chose to deliver it.

We seem to be at a pivotal point. Public attitudes have shifted providing a unique opportunity that could be squandered if we don’t get it right. Two things must change for the movement away from systemic enmity to have any staying power. One is that individual human hearts and minds must change, the other is that there must be societal, larger system changes that do not favor some at the expense of others. If both things do not happen, there will be more George Floyds and violent protests.

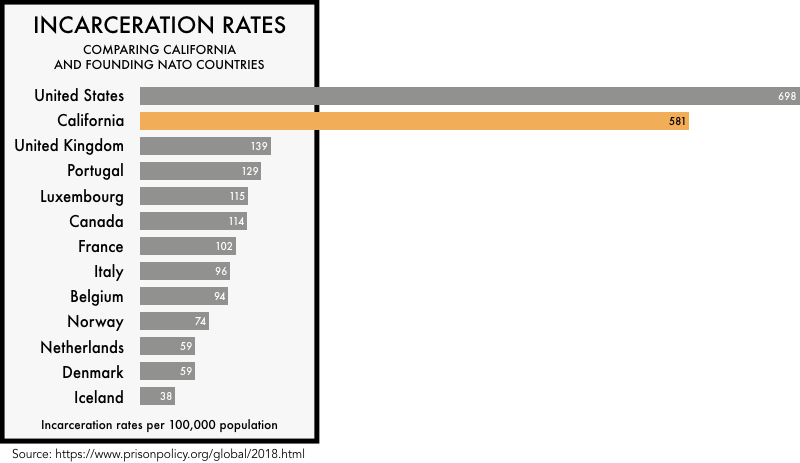

Economics as System

Strong arguments have been made that two of the many reasons that black people, and especially black men, are incarcerated at far higher rates than their white, Asian, or Hispanic counterparts are racial bias and inferior legal representation. Combined, these help to account for the wildly disproportionate numbers of imprisoned blacks versus whites per capita. Pew research data shows that in 2017, there were 1,549 black prisoners for every 100,000 black adults—nearly six times the imprisonment rate for whites (272 per 100,000) and nearly double the rate for Hispanics (823 per 100,000).

Given the economic realities of average income, it is much more difficult for a black man to receive a defense on par with a white man. Blind lady justice, a worthy ideal, isn’t so blind when financial inequities so influence the fairness of outcomes. Being able to mount a strong, and therefore, costly defense should not be the privilege of the wealthy alone.

Sadly, any alternatives to an economics-based legal system, where they have been tried, result in far worse outcomes—as in years of Stalin’s gulags where a single group of oligarchs determined the fate of rich and poor alike in order to stamp out any political opposition. By 1936, the Gulags held more than 5 million prisoners. Another illustration is in Venezuela today where President Nicolas Maduro has taken control over the judiciary as well as the legislative branch of the government.

Although I do not see a strong, viable alternative to a system of justice based on economics, I do see ways to mitigate the impact. One way is to reform our current criminal justice system in ways that decriminalize malum prohibitum infractions. Per prison policy.org, “For four decades, the U.S. has been engaged in a globally unprecedented experiment to make every part of its criminal justice system more expansive and more punitive. As a result, incarceration has become the nation’s default response to crime, with, for example, 70 percent of convictions resulting in confinement.”

Added to the incomprehensible number of prohibitions for which one can be incarcerated is the tightening of constitutional interpretation by courts as elaborated by Tahir Duckett in the Atlantic.

“…criminal law, courts have repeatedly narrowed the scope of the Constitution’s protections over the past 50 years—the time period coinciding with the rise of mass incarceration—without requiring the government to prove that these limitations are justified.”

At the bottom, the most downstream problem is enmity, which creates a retributive justice system rather than a rehabilitative one. Black men have the most to lose in a ramped-up, punitive justice system, and I would argue, also the most to gain in a system based on mercy and restoration, dignity and quality of life.

Justice and Mercy

If you were to place Justice and Mercy at either end of a continuum with a fulcrum in the middle, the United States government would arguably bear the weight of an anvil size weight on the justice side and mere feathers on the mercy side. Demands for justice are ubiquitous. Justice has even crept into our mercy language with terms like “Social Justice.” The problem with calling what ought to be termed Mercy, Justice, is that there is no focus on the real crux of the matter: Legal Reform.

Justice generally equates with condemnation and therefore punitive outcomes, while Mercy represents liberation

Said another way, Justice generally equates with condemnation and therefore punitive outcomes, while Mercy represents liberation. Criminal courts in the United States are largely oriented towards condemnation, and therefore punishment-based. What if courts were more oriented towards mercy and reconciliation—as reflected in the growing movement towards restorative justice?

Portugal tried a Mercy based legal system for drug offenses. The results are astounding. As drugs were decriminalized in 2001 and money previously intended for costly incarceration was shifted toward rehabilitation, contrary to nearly all predictions of the disaster that would ensue, nearly every relevant statistic improved (for a more thorough reading of the Portugal experience, see Glenn Greenwald’s White Paper for the Cato Institute).

The tie back to the heavy black incarceration rates in the United States is this: A black person would not need to rely so much on an adequate and therefore expensive legal defense if penalties were not so stringent, more rehab focused, and yes, many non-violent activities were even decriminalized.

Having said all this, it seems to be built into our national psyche that punishment for crimes is the best deterrent. The data, however, simply do not bear this out. It seems that many candidates, especially for Attorney General, run on a platform of being “tough on crime,” which means punitive responses to crime (even crime that has no victim). Tough justice criminal outcomes do several things to encourage more criminal behavior. Two of which are the forced association of the mildly criminal with their much more hardened counterparts in the prison system, along with the associated lack of employment opportunities and permanent labeling once time has been served.

However frightening “Defund the Police” sounds as a label, I understand its intention as a call to balance systemic Mercy and Justice. Said differently, it is a rethinking and a remaking of elements that protect civil society. It is a call to defund systemic enmity.

Systemic Favoring

There is arduous, protracted work ahead for those who want to reduce enmity reflected in the systems around us. Decriminalization is one example. War policy is another. The changes outlined would especially adjust the scales of justice in favor of a more equal opportunity for black men and therefore, black families, but also for all Americans.

Along with the long term, universal, and ongoing work of rooting out enmity in our own human hearts and minds, there is an immediate opportunity to address the source of the systemic enmity associated with our national, festering wound of black inequity.

And on the path to get there, may we press ourselves to stay open to insights that don’t align with our previous biases or perspectives. As one deflated police officer put it this week, “whether you’re right or wrong, it doesn’t matter right now. No one is listening. Any justified action is getting twisted.”

We can do better than that. And for the sake of those most vulnerable among us, we must do better.