The events of the last several years are a stark reminder that we live in an age which, at times, seems almost destitute of peace. As UN Secretary-General António Guterres recently said, “Our world is becoming unhinged. . . . And we seem incapable of coming together to respond.” Racial tensions continue to reverberate here and abroad. Refugees stream across borders seeking safety and shelter. Religious intolerance is on the rise, and fanatical ideological adherence fuels extremism, resulting in inexcusable persecution and loss of life. Continued suicide bombings and mass shootings in schools and places of worship senselessly steal the lives of thousands of harmless victims, as do food insecurity, human trafficking, and gang violence in many places around the world. Nearly two years on, the tragic, unprovoked invasion of Ukraine continues, now accompanied by the searing pain of the Israeli-Gaza war. These and many other challenges confront millions who, in the words of Elder Dale G. Renlund, face “infuriating unfairness.”

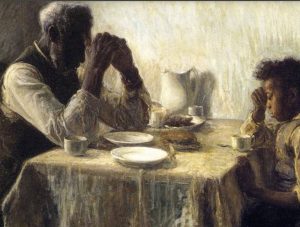

Such stifling injustices are a manifestation of the worst kind of climate change—a global warming of hostility and hatred that is laying waste to the hearts of humankind. Society’s twin pillars of civility and charity are crumbling. Love of neighbor is being replaced by disregard for neighbor. The rancor of our political discourse reflects a deep-seated contempt for the perspectives of others that spreads through social media channels with an almost combustible virulency. And taken together, the eradication of racism and the elimination of poverty constitute an urgent, pressing work that remains far from complete. The difficulties experienced by and evils perpetuated against innocent and repressed people cry out, as did Martin Luther King Jr., for justice that rolls “down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.”

It seems society has adopted the contemptuous attitude of Latimer, the narcissistic narrator in George Eliot’s novella The Lifted Veil (1859), who, in his dying days, described the scorn and disdain with which humankind treat one another:

While the heart beats, bruise it—it is your only opportunity; while the eye can still turn towards you with moist, timid entreaty, freeze it with an icy unanswering gaze; while the ear, that delicate messenger to the inmost sanctuary of the soul, can still take in the tones of kindness, put it off with hard civility, or sneering compliment, or envious affectation of indifference; while the creative brain can still throb with the sense of injustice, with the yearning for brotherly recognition—make haste—oppress it with your ill-considered judgments, your trivial comparisons, your careless misrepresentations.

The severity of our social and spiritual condition should awaken each of us to take more determined and deliberate steps to create a just and civil society. But that task, worthy in its aim, seems increasingly formidable, even impossible, in its execution. Ironically, our magnified view of the world’s injustices seems to diminish our belief that we can do anything to help solve them. Difficulties, whether close or far, loom so large that we often feel powerless to shoulder them. We delegate their solutions to governments or charitable organizations, hoping some wisdom will prevail in the hearts of those who lead them. We then turn our hearts inward, trying to untangle our own problems and seek solace for our own hurts, forgetting or ignoring the needs of those around us. Civility and charity are crumbling.

And what are those necessities? After food, said John Stuart Mill, our security is “the most vital of all interests” and “the most indispensable of all necessaries.” It is something “no human being can possibly do without; on it, we depend for all our immunity from evil, and for the whole value of all and every good.” That security, says Mills, arises from the claim we have “on our fellow creatures to join in making safe for us the very groundwork of our existence.”

Indeed, we are bound together in making one another secure; we are in the same boat and of the same body. All of this is well and good. Yet even when motivated by our most noble and principled hopes and our staunchest determination, we come to realize our efforts will prove inadequate when measured against the staggering sum of the needs of humanity this moment in history presents us.

Perhaps it was such a realization that prompted Gilbert Kilpack’s 1946 reflection on the emptiness of the peace that ensued after the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Then a secretary in the Stony Brook Friends Meeting in Baltimore, Kilpack believed that after enduring “so long and bitter a conflict, it became necessary to see ourselves clothed in righteousness, but it was self-righteousness—which frequently conquers, but never makes, peace.” There is, Kilpack continued,

something of God in every man, let us affirm it more certainly than ever, but surrounded as we are by millions of new-made graves and with the voices of the hungry and the dispossessed in our ears, let us not easily accept the impious hope that the natural goodness of ourselves is sufficient stuff out of which to fashion a better world.

Dismissing what he saw as the “dominant hope” lingering “in millions of minds” that “man is sufficient unto himself and has but to strive to bring the good new kingdom in,” he gives this glaring warning:

Hear me, I cry it with all my strength, and my voice rises out of the suffering and the bitter crucible of our times: man is not by nature good. We are all born with a freedom to turn to the good, but the Source of good is Beyond, and the power of human transformation is a given power. We may labor, study, and weep for it, which we must do, but in the end, it is given.

Now, more than seventy-five years later, Killpack’s exhortation speaks with a prescient thunder, for he was right: healing the pains of hunger and the wounds of war and inequality, bridging the chasms spanning society’s most deeply divided issues and resolving our differences—especially differences that polarize and paralyze us and evoke conflict and contention—will never be accomplished unless we turn to powers higher than those we possess.

Realizing our need to turn to such powers, this is a season to remember how God has turned to us. He sent His Son, who “left worlds of light” to become “the meek and lowly One.” Christ descended into our world to know our pain. It was, said Matthew Henry, “a great step downward, considering the glories of the world he came from and the calamities of the world he came to.” We are bound together in making one another secure.

Never was there a poorer man than Christ; He was the prince of poverty. . . . He who scattered the harvest o’er the broad acres of the world, had not sometimes wherewithal to stay the pangs of hunger? He who digged the springs of the ocean, sat upon a well and said to a Samaritan woman, “Give me to drink!” He rode in no chariot, He walked his weary way, footsore, o’er the flints of Galilee! . . . . [H]e said, “Foxes have holes, and the birds of the air have nests; but I, the Son of man, have not where to lay my head.” He who had once been waited on by angels becomes the servant of servants, takes a towel, girds himself, and washes his disciples’ feet! He who was once honored with the hallelujahs of ages is now spit upon and despised! . . . . Oh, for words to picture the humiliation of Christ! What leagues of distance between Him that sat upon the throne, and Him that died upon the cross! . . . . Trace him, Christian, He has left thee His manger to show thee how God came down to man. He hath bequeathed thee His cross to show thee how man can ascend to God. . . . Oh, Son of Man, I know not which to admire most, thine height of glory, or thy depths of misery!

Matthew Henry suggests we should ask “with wonder,” “What moved Him to such an expedition?”

Jesus answered simply: “I am come a light into the world,” He taught, “to seek and to save that which was lost.”

As His followers, seeking and saving now become our mission as well. Christ commands us to “condescend to men of low estate,” to “lift up the hands which hand down,” and to “heal the brokenhearted.” He asks us labor with Him to love and comfort those whose losses have drained the reservoirs of their hope, to feed those whose hunger can only be satisfied by the Bread of Life. He asks us to live the principles of His gospel, which radically contradict the world’s intemperate and revenge-filled ways. In a time of war, Jesus calls us to be peacemakers. He counsels us to agree with our adversaries quickly. He pleads with us to be meek and merciful. He invites us to treat others as we would want to be treated.

Then, among all these commandments comes “the admonition that challenges each of us,” said President Russell M. Nelson: “Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you.” When we do these things, we can “literally change the world—one person and one interaction at a time.”

Of course, the full measure of the salvation Christ extends to us awaits His next coming, when He will reign supreme and when every knee shall bow, and every tongue confess He is the King come again to reign eternally. Then all the dead, billions upon billions, shall rise in resurrection, and all “they who have believed in the Holy One of Israel, they who have endured the crosses of the world, and despised the shame of it, they shall inherit the kingdom of God, which was prepared for them from the foundation of the world, and their joy shall be full forever.”

Yes, our world is becoming increasingly “unhinged.” But we need not, we cannot become hopeless. The words spoken by Martin Luther King Jr. nearly sixty years ago as he received the Nobel Peace Prize remind us that change is possible, even inevitable:

I accept this award today with an abiding faith in America and an audacious faith in the future of mankind. I refuse to accept despair as the final response to the ambiguities of history. . . . I refuse to accept the view that mankind is so tragically bound to the starless midnight of racism and war that the bright daybreak of peace and brotherhood can never become a reality.

I still believe that one day mankind will bow before the altars of God and be crowned triumphant over war and bloodshed, and nonviolent redemptive good will proclaim the rule of the land.

King’s powerful conviction invites us to deal with our personal and global challenges using a more active love born of faith in Christ’s redemption and fueled by a covenant of commitment to join with Him in the remaking of the world. Motivated by such love, we can be assured that the wrong will fail and the right prevail. And we can have peace, knowing that in Christ, all things will become new.

Like Jesus did throughout His life, let’s determine to spend more time this year with the poor and those low in spirit, with the homeless and lonely, with the sick and the hungry. Let’s love our enemies. To these and to all, we must minister with His mercy and join Him in the cause of justice.

How shall we begin?

“Someone, “ said King, “must have sense enough and morality enough to cut off the chain of hate. This can be done only by projecting the ethic of love to the center of our lives.”