After reading the first installment in this series (here), you might have been left wondering what I was getting at when I claimed that our faith crises may be the result of having unwittingly absorbed certain problematic premises from the larger, secular culture and our engagement with and immersion in it. Perhaps you are saying to yourself:

“I don’t know what he’s talking about. It seems to me that most of those of us who count ourselves among ‘the believers’ are doing a pretty good job every day striving to be ‘in the world but not of the world’ so as to remain ‘unspotted from the world.’ Unlike the ‘unchurched’ hedonists in Hollywood, most of us religious folks obey the Ten Commandments, attend church regularly, donate to good causes and pay our tithing, keep our yards clean and neat, avoid gossip and pornography, do our best to raise responsible children—and feel properly guilty when we lose our tempers with them—and even teach Sunday School when we’re asked to do so.”

Now, first off, in no way do I mean to dismiss or deny the many good, and often difficult, things that so many do as part of the observance of their faith, things that are very often very much at odds with the accepted beliefs, values, and practices that pervade our larger, more secular culture. However, I nonetheless want to draw attention to the possibility that there is more at play here than simply establishing whether we as Christians happen to believe a few things or do a few things that outsiders might consider peculiar, or primitive, or even downright dumb. I want to explore how it might be that we absorbed certain secular ideas and assumptions, typically without ever fully realizing that we have done so—ideas and assumptions that are, I will argue, hostile and corrosive to our most cherished religious beliefs and aspirations.

In his essay The Overlooked Bondage of Our Common Sense, James Faulconer trenchantly observed:

“The tightest cords of bondage are those we are unaware of. The most willing slave does not recognize that she is a slave, thinking that what she does is what she has chosen to do though she has been manipulated into doing it. We are most in danger of this particular bondage when what we think or do seems ‘perfectly natural’ or ‘perfectly reasonable.’ The things that we think are beyond question are the very things that can most easily deceive us to the point of bondage.”

In other words, despite our sincerest efforts to live our lives in harmony with what we take to be gospel teachings, we may nonetheless take on certain ways of thinking, certain ideas, certain values and perspectives, which are actually quite insidiously toxic to a vibrant and coherent Christian faith. One reason that such ways of thinking are so easily and smoothly absorbed is, by and large, because they tend to seem so commonsensical to us, so ordinary and reasonable – just unquestionably the way things really are. And, they can seem to be so precisely because no one ever really questions them, or encourages them to be seriously questioned.

The famous author, professor, and Christian apologist C. S. Lewis begins his book The Abolition of Man with a powerful essay entitled “Men Without Chests.” In this essay, Lewis provides an excellent example of exactly how it is that we can come to embrace certain ideas, thinking of them merely as common sense—ideas that in time can actually prove to be corrosive to our religious beliefs and practices. Lewis begins his essay by discussing a subtle way in which relativism (moral and otherwise) can be imparted by means of a certain seemingly innocuous passages in a commonly used textbook for elementary school students of his day, a book he dubs The Green Book (There is no connection whatsoever here to the title or topic of the recent Oscar-winning movie). The authors of the textbook, whose names Lewis omits out of respect, relate a well-known story in which the famous English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge overhears two tourists describing a waterfall, one of them calling the waterfall “sublime” and the other calling it “pretty.” The textbook authors then write:

“When the man said This is sublime, he appeared to be making a remark about the waterfall . . . Actually . . . he was not making a remark about the waterfall, but a remark about his own feelings. What he was saying was really I have feelings associated in my mind with the word “Sublime,” or shortly, I have sublime feelings . . . This confusion is continually present in language as we use it. We appear to be saying something very important about something: and actually we are only saying something about our own feelings.”

The consequences of all this, Lewis notes, is that “The schoolboy who reads this passage in The Green Book will believe two propositions: firstly, that all sentences containing a predicate of value are statements about the emotional state of the speaker, and secondly, that all such statements are unimportant.” In other words, in studying this text students come not only to learn the fundamentals of English grammar and usage (as intended) but far more subtly and insidiously they also come to learn what Lewis identifies as moral subjectivism.

According to Lewis scholar Adam C. Pelser, “[Moral] Subjectivism is the view that value claims such as ‘Murder is wrong,’ which might seem to be claims about objective (mind-independent) values, are simply reports about the subjective emotions of the speaker (e.g., ‘I have a disapproving feeling toward murder’), which are no more about objective values than statements such as ‘I have an itch’ or ‘I’m going to be sick’.” Now, Professor Lewis is clear that the textbook’s authors have said none of these things, at least not explicitly. Rather, he points out that “The pupils are left to do for themselves the work of extending the same treatment to all predicates of value: and no slightest obstacle to such extension is placed in their way.” In the end, Lewis’ concern is not so much with the authors’ intentions behind what they have written, whether they are being nefarious or simply naïve and sloppy, but “with the effect their book will certainly have on the schoolboy’s mind.”

He continues:

Their words are that we ‘appear to be saying something very important’ when in reality we are ‘only saying something about our own feelings’. No schoolboy will be able to resist the suggestion brought to bear upon him by that word only. I do not mean, of course, that he will make any conscious inference from what he reads to a general philosophical theory that all values are subjective and trivial. The very power of [the book’s authors] depends on the fact that they are dealing with a boy: a boy who thinks he is ‘doing’ his ‘English prep’ and has no notion that ethics, theology, and politics are all at stake. It is not a theory they put into his mind, but an assumption, which ten years hence, its origins forgotten and its presence unconscious, will condition him to take one side in a controversy which he has never recognized as a controversy at all.

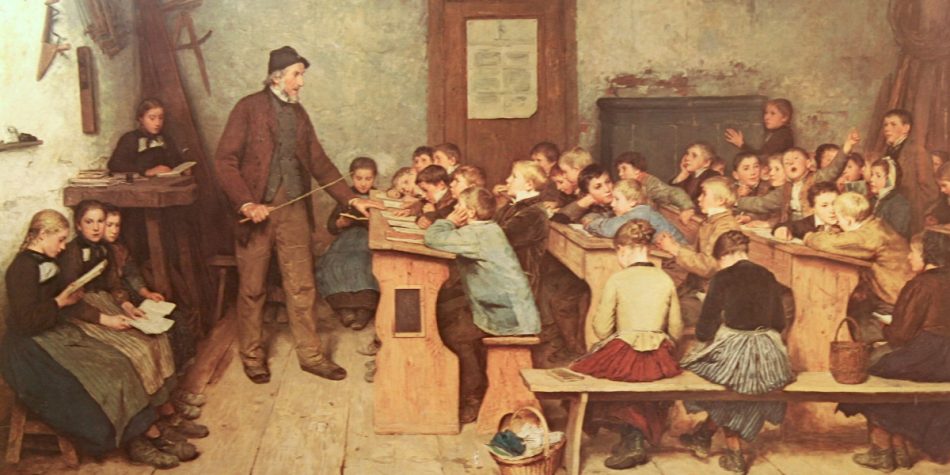

Lewis’s central worry here is the way in which both the assumptions and values that undergird the passages the student reads in this particular textbook exert an unseen but profound influence on the development of the student’s most basic understanding of themselves, of the world, and of God. The influence of these hidden assumptions and values is so powerful precisely because they are latent, things merely implied in passing, inscribed in a sort of invisible ink on the white space between the words and sentences manifest on the page. Such indoctrination—and make no mistake this is a process of indoctrination—takes place by means of a sort of educational and cultural osmosis through which an entire worldview slowly accretes over time like sediment in a river delta, both taking shape in and giving shape to the student’s mind, desires, and aspirations. It is only over time that this process manages to turn young, eager, trusting students, Lewis argues, into “men without chests.” Indeed, as Lewis has elsewhere written, “the sources of unbelief among young people today do not lie in those young people. The outlook which they have . . . is a backwash from an earlier period. It is nothing intrinsic to themselves which holds them back from the Faith.”

Lewis’ argument is particularly relevant in our day, across a variety of situations in modern life, and thus has much to teach us about how exactly it is we come to possess certain perspectives and assumptions, taking them for granted, as mere commonsense, as we go about trying to make sense of ourselves, others, God, and the world around us. Additionally, his vignette offers a clear warning about the very dangerous consequences that will almost surely attend the attempt to understand our religious commitments and traditions against a backdrop of unrecognized secular assumptions, especially when those assumptions masquerade as confirmed certainties, received wisdom, and common knowledge about things as they just happen to be. After all, Lewis contends, “a man whose mind was formed in a period of cynicism and disillusion, cannot teach of hope or fortitude.”

In 1945 Lewis delivered a speech to a group of Anglican pastors and youth leaders in which he described what he took to be the central challenge of Christian apologetics or the direct and explicit defense of the reasonableness and coherence of the Christian faith. Lewis recognized that while it is a worthy endeavor in its own right, the formal work of apologetics faces an immense challenge in its efforts to win hearts and minds, strengthen the faith commitments of believers, and invite others to “come unto Christ.” He noted:

We can make people (often) attend to the Christian point of view for half an hour or so; but the moment they have gone away from our lecture or laid down our article, they are plunged back into a world where the opposite position is taken for granted. As long as that situation exists, widespread success is simply impossible . . . Our Faith is not very likely to be shaken by any book on Hinduism. But if whenever we read an elementary book on Geology, Botany, Politics, or Astronomy [and, as a psychologist, I would add Psychology], we found that its implications were Hindu, that would shake us. It is not the books written in direct defense of Materialism [i.e., secularism] that make the modern man a materialist; it is the materialistic assumptions in all the other books.

You see, ideas, facts, findings, insights, arguments, what have you, do not come into the world, and are not communicated to us, as isolated bits of information, as atoms of knowledge existing pristinely independent of context or background suppositions. Rather, the information we glean from the textbooks we read, the podcasts we listen to, the lectures we attend, the movies and television shows we watch, stream and binge, is always grounded in some worldview, some set of (usually unquestioned) assumptions about the nature of the world and what about it is worth knowing or saying. Our worldview is our most basic framework of understanding, it is the foundation of meaning we live in and through as we go about making sense of the world and our place and purpose in it. And, as such, our worldview is one of the most important things about us because it constitutes the lens through which we interpret the world, others, ourselves, and God.

Despite the pervasiveness of what has been termed “the myth of neutrality”—a very popular modern myth about the nature of science—educational researcher Kathy Hall reminds us, “No knowledge is neutral, but rather is always based on some . . . perception of reality and on some . . . perspective of what is important to know.” Similarly, Professor of Cultural Studies Randi R. Warne, writes, “Knowledge production is not a neutral process. Who is asking the question determines in large measure what questions are asked.” Knowing this, Lewis cautions us to sup carefully as we learn and study so that we do not consume a rival worldview, one hostile to our Christianity, one that seeks to repudiate and replace it, without a clear awareness and understanding of what exactly it is we are doing and what its likely consequences might prove to be.

G.K. Chesterton once trenchantly observed, “For a landlady considering a lodger, it is important to know his income, but still more important to know his philosophy.” And more important still, I believe, is to know our own philosophy, our own assumptions about reality, knowledge, truth, and reason. Clearly understanding where we stand and why, as well as where our assumptions inevitably lead is not, however, an easy task. It requires a great deal of intellectual and spiritual resolve, as well as a genuine willingness to probe deeply into what are often unspoken and murky presumptions and to think them through to their logical conclusions. More often than not, it also requires the services of a trustworthy guide, one who has intimate knowledge of the intellectual terrain, its pitfalls and dangers, important landmarks and signposts, fruitful pathways and deadends. At the least, it calls for a guide who has successfully made the journey before and who well knows the way, its hazards and its likely outcomes.

Of course, textbooks, classroom lectures, library stacks, podcasts, and video screens are not the only places where we might find ourselves unwittingly absorbing the tenets and assumptions of a secular worldview. Christian philosopher James K. A. Smith has written and spoken extensively on what he identifies as “secular liturgies.” Typically understood to refer to religious activities and rituals, most often public in nature, by which individuals worship together, liturgies constitute “identity-forming practices” meant to shape and refine the contours of one’s religious life and self-understanding in a very concrete and embodied and social manner. “For those who practice faith,” Smith writes, “faith takes practice. And such practice is embodied and material; it is communal and liturgical; it involves eating and drinking, dancing and kneeling, painting and singing.” As such, liturgical practices ground and guide and nurture our desires and imagination in ways that define for us the meanings of our lives in subtle, nuanced, and intimate ways because they are “loaded with an ultimate Story about who we are and what we’re for.” Smith further notes, “they carry with them a kind of ultimate orientation” that points us toward a deeper understanding of our nature, purpose, the meaning of our lives, and those moral and spiritual goods to which we ought to aspire.

One need only think of rituals such as baptism, partaking of the Eucharist, blessing infants, laying on of hands to heal the sick, communal prayer and scripture study, temple and church weddings, as well as the daily observance of various rituals associated with modesty and chastity and healthy living to see how such things are powerfully liturgical in nature. This is especially clear as one considers how such ritual observances embody ways of conveying truth and deepening personal understanding quite different than we would otherwise encounter if we just confined ourselves to the systematic analysis of sacred texts, or the study of abstract doctrines and formal beliefs, or the history of ideas. Liturgies involve the whole person in what is at best only a partially cognitive or intellectual task of sense-making, inviting immersion in communal activity and embodied engagement in the complexities of a meaningful life, rather than calling for retreat into solitary critical or intellectual reflection.

However, although usually associated only with religion, “there are practices and institutions that have the same function and force” as religious liturgies, Smith argues, but we do not usually recognize them as such, even though they, too, embody “rituals and practices that shape our attunement to what is ultimate.” There are indeed powerful, soul-shaping secular liturgies in which we participate on an almost daily basis. These are liturgies that orient us toward a “rival understanding of the good life,” but which we—in our immersion in the secular world of common cultural practice that gives birth to, and sustains and nurtures, such a rival understanding—seldom, if ever, actually recognize as liturgical rituals meant to shape and form our minds and hearts. And because we do not recognize these “secular liturgies” in which we so often participate to be liturgies in the first place, we have little sense of how they are continually shaping and guiding us toward new and different conclusions than those consonant with our faith. As Smith notes, “when such liturgies are disordered, aimed at rival kingdoms, they are pointing us away from our magnetic north in Christ. Our loves and longings are steered wrong, not because we’ve been hoodwinked by bad ideas, but because we’ve been immersed in de-formative liturgies and not realized it. As a result, we absorb a very different Story about the telos of being human and norms of flourishing.” In short, secular liturgies smooth the way for our transition into a rival account of what it means to be human, one in which being human is oriented toward very different aims and purposes than those found in a Christian worldview. Most insidiously, however, is the fact that the transition often takes place so far downstream from any real examination of the core issues involved and the implications at stake.

Smith has examined in considerable detail such secular liturgies—or what he has termed “pedagogies of desire”—as “the liturgies of mall and market,” the liturgies of nationalism, entertainment, and the stadium, as well as the “liturgy of the university.” In each case, he shows how the ordinary activities of our daily social and political lives are shot-through with assumptions about the nature of truth, God, the human soul, and the good life—assumptions that rival those at the conceptual foundation of genuine Christian worship and understanding. Unfortunately, because these activities are so common-place, so utterly ordinary and widely shared—the nature of the assumptions underlying them, and the profoundly corrosive implications of those assumptions, both for self-understanding and for understanding the meaning and possibilities of religious faith, often go unnoticed—even as doubts about our faith mount and commitment to our covenants wanes. A lesson we might take here from thinkers like Faulconer, Lewis, and Smith is that the doubts we entertain that lead us to question our faith may not be as innocent as they seem, they may not arise from the places we think, but rather may stem from sources unrecognized and unreliable. To know one way or the other, however, it is incumbent that we do more than just entertain our doubts and questions, simply following wherever they may happen to lead us. Rather, we must be willing to seriously question our questions and doubt our doubts. To paraphrase the philosopher and political activist Cornel West, we must realize that genuine understanding only begins as we “interrogate [our] assumptions.”