The Social Dilemma is a newly available documentary on Netflix about the peril of social networks.

The documentary does a decent job of introducing some of the ways social networks (Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, etc.) are negatively impacting society. If this is your entry point to the topic, you could do worse.

But if you’re looking for a really thorough analysis of what is going wrong or for possible solutions, then this documentary will leave you wanting more. Here are four specific topics—three small and one large—where The Social Dilemma fell short.

AI Isn’t That Impressive

I published a piece in June on Why I’m an AI Skeptic and a lot of what I wrote then applies here. Terms like “big data” and “machine learning” are overhyped, and non-experts don’t realize that these tools are only at their most impressive in a narrow range of circumstances. In most real-world cases, the results are dramatically less impressive.

The reason this matters is that a lot of the oomph of The Social Dilemma comes from scaring people and AI just isn’t actually that scary.

I don’t fault the documentary for not going too deep into the details of machine learning. Without a background in statistics and computer science, it’s hard to get into the details. That’s fair.

I do fault them for sensationalism, however. At one point Tristan Harris (one of the interviewees) makes a really interesting point that we shouldn’t be worried about when AI surpasses human strengths, but when it surpasses human weaknesses. We haven’t reached the point where AI is better than a human at the things humans are good at—creative thinking, language, etc. But we’ve already long since passed the point where AI is better than humans at things humans are bad at, such as memorizing and crunching huge data sets. If AI is deployed in ways that leverage human weaknesses, like our cognitive biases, then we should already be concerned. So far this is reasonable, or at least interesting.

But then his next slide (they’re showing a clip of a presentation he was giving) says something like “Checkmate humanity.”

I don’t know if the sensationalism is in Tristan’s presentation or The Real Dilemma’s editing, but either way, I had to roll my eyes.

All Inventions Manipulate Us

At another point, Tristan tries to illustrate how social media is fundamentally unlike other human inventions by contrasting it with a bicycle. “No one got upset when bicycles showed up,” he says. “No one said… we’ve just ruined society. Bicycles are affecting society, they’re pulling people away from their kids. They’re ruining the fabric of democracy.”

Of course, this isn’t really true. Journalists have always sought sensationalism and fear as a way to sell their papers, and—as this humorous video shows—there was lots of panic around the introduction of bicycles.

Every successful human invention changes behavior individually and collectively.

Tristan’s real point, however, is that bicycles were a passive invention. They don’t actively badger you to get you to go on bike rides. They just sit there, benignly waiting for you to decide to use them or not. In this view, you can divide human inventions into everything before social media (inanimate objects that obediently do our bidding) and after social media (animate objects that manipulate us into doing their bidding).

That dichotomy doesn’t hold up.

First of all, every successful human invention changes behavior individually and collectively. If you own a bicycle, then the route you take to work may very well change. In a way, the bike does tell you where to go.

To make this point more strongly, try to imagine what 21st century America would look like if the car had never been invented. No interstate highway system, no suburbs or strip malls, no car culture. For better and for worse, the mere existence of a tool like the car transformed who we are both individually and collectively. All inventions have cultural consequences like that, to a greater or less degree.

Second, social media is far from the first invention that explicitly sets out to manipulate people. Propaganda, disinformation campaigns, and psyops are one obvious category of examples with roots stretching back into prehistory. But, to bring things closer to social networks, all ad-supported broadcast media have basically the same business model: manipulate people to captivate their attention so that you can sell them ads. That’s how radio and TV got their commercial start: with the exact same mission statement as Gmail, Google search, or Facebook.

So much for the idea that you can divide human inventions into before and after social media. It turns out that all inventions influence the choices we make and plenty of them do so by design.

That’s not to say that nothing has changed, of course. The biggest difference between social networks and broadcast media is that your social networking feed is individualized.

With mass media, companies had to either pick and choose their audience in broad strokes (Saturday morning for kids, prime time for families, late night for adults only) or try to address two audiences at once (inside jokes for the adults in animated family movies marketed to children). With social media, it’s kind of like you have a radio station or a TV studio that is geared just towards you.

Thus, social media does present some new challenges, but we’re talking about advancements and refinements to humanity’s oldest game—manipulating other humans—rather than some new and unprecedented development with no precursor or context.

Consumerism is the Real Dilemma

The most interesting subject in the documentary, to me at least, was Jaron Lanier. When everyone else was repeating that cliché about “you’re the product, not the customer” he took it a step or two farther. It’s not that you are the product. It’s not even that your attention is the product. What’s really being sold by social media companies, Lanier pointed out, is the ability to incrementally manipulate human behavior.

This is an important point, but it raises a much bigger issue that the documentary never touched.

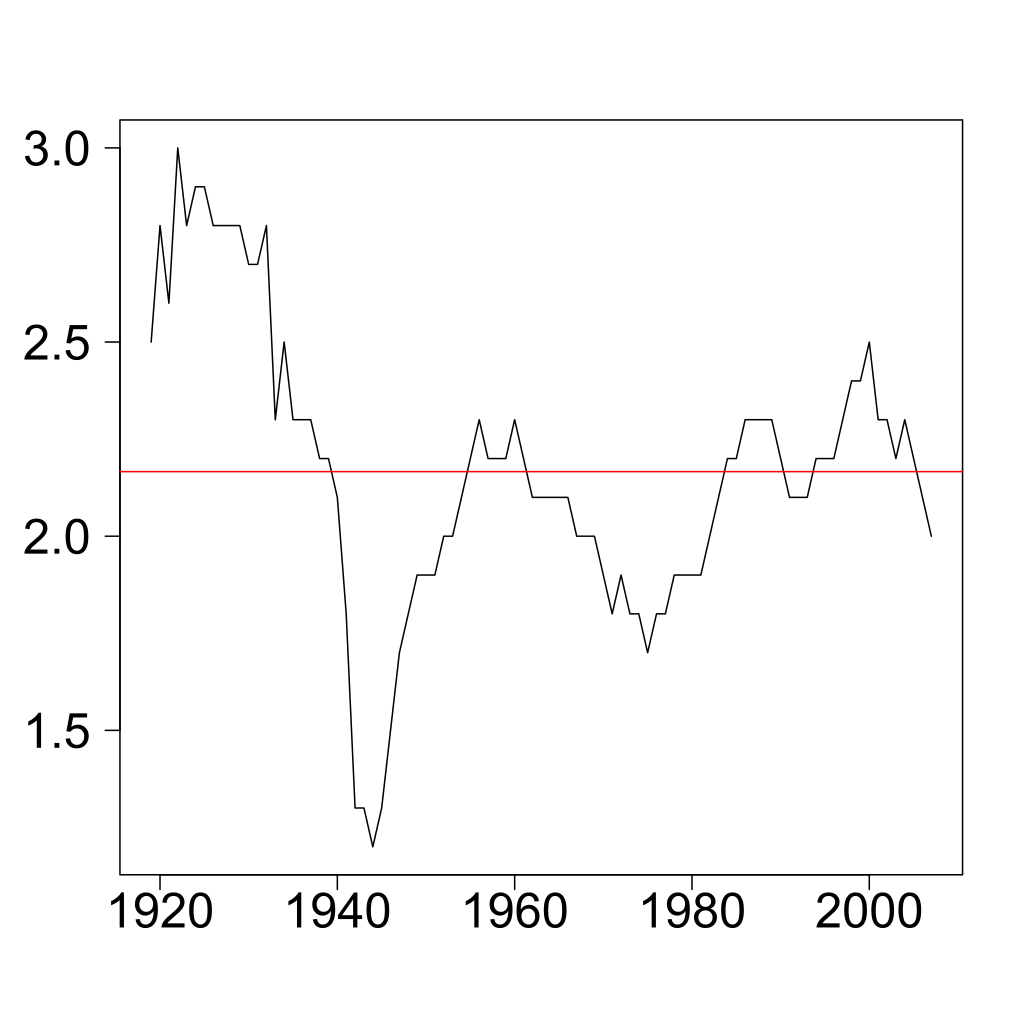

This is the amount of money spent in the US on advertising as a percent of GDP over the last century:

Source: Wikipedia

It’s interesting to note that we spent a lot more (relative to the size of our economy) on advertising in the 1920s and 1930s than we do today. What do you think companies were buying for their advertising dollars in 1930 if not “the ability to incrementally manipulate human behavior”?

Because if advertising doesn’t manipulate human behavior then why spend the money? If you can’t manipulate human behavior with a billboard or a movie trailer or a radio spot, then nobody would ever spend money on any of those things.

This is the crux of my disagreement with The Social Dilemma. The poison isn’t social media. The poison is advertising. The danger of social media is just that (within the current business model) it’s a dramatically more effective method of delivering the poison.

Let me stipulate that advertising is not an unalloyed evil. There’s nothing intrinsically wrong with showing people a new product or service and trying to persuade them to pay you for it. The fundamental premise of a market economy is that voluntary exchange is mutually beneficial. It leaves both people better off.

And you can’t have voluntary exchange without people knowing what’s available. Thus, advertising is necessary to human commerce and is a part of an ecosystem flourishing, mutually beneficial exchanges, and healthy competition. You could not have modern society without advertising of some degree and type.

That doesn’t mean the amount of advertising—or the kind of advertising—that we accept in our society is healthy. As with basically everything, the difference between poison and medicine is found in the details of dosage and usage.

There was a time, not too long ago, when the Second Industrial Revolution led to such dramatically increased levels of production that economists seriously theorized about ever shorter workweeks with more and more time spent pursuing art and leisure with our friends and families. Soon, we’d spend only ten hours a week working, and the rest developing our human potential.

And yet in the time since then, we’ve seen productivity skyrocket (we can make more and more stuff with the same amount of time) while hours worked have also remained roughly steady. The simplest reason for this? We’re addicted to consumption. Instead of holding production basically constant (and working fewer and fewer hours), we’ve tried to maximize consumption by keeping as busy as possible. This addiction to consumption, not necessarily having but to acquiring stuff, manifests in some really weird cultural anomalies that—if we witnessed them from an alien perspective—probably strike us as dysfunctional or even pathological.

I’ll start with a personal example: when I’m feeling a little down I can reliably get a jolt of euphoria from buying something. Doesn’t have to be much. Could be a gadget or a book I’ve wanted on Amazon. Could be just going through the drive-thru. Either way, clicking that button or handing over my credit card to the Chick-Fil-A worker is a tiny infusion of order and control in a life that can seem confusingly chaotic and complex.

It’s so small that it’s almost subliminal, but every transaction is a flex. The benefit isn’t just the food or book you purchase. It’s the fact that you demonstrated the power of being able to purchase it.

From a broader cultural perspective, let’s talk about unboxing videos. These are videos—you can find thousands upon thousands of them on YouTube—where someone gets a brand new gizmo and films a kind of ritualized process of unpacking it.

This is distinct from a product review (a separate and more obviously useful genre). Some unboxing videos have little tidbits of assessment, but that’s beside the point. The emphasis is on the voyeuristic appeal of watching someone undress an expensive, virgin item.

And yeah, I went with deliberately sexual language in that last sentence because it’s impossible not to see the parallels between brand newness and virginity, or between ornate and sophisticated product packaging and fashionable clothing, or between unboxing an item and unclothing a person. I’m not saying it’s literally sexual, but the parallels are too strong to ignore.

This rampant consumerism isn’t making us objectively better off or happier.

These do not strike me as the hallmarks of a healthy culture, and I haven’t even touched on the vast amounts of waste. Of course, there’s the literal waste, both from all that aforementioned packaging and from replacing consumer goods (electronics, clothes, etc.) at an ever-faster pace. There’s also the opportunity cost, however. If you spend three or four or ten times more on a pair of shoes to get the right brand and style than you could on a pair of equally serviceable shoes without the right branding, well… isn’t that waste? You could have spent the money on something else or, better still, saved it, or even worked less.

This rampant consumerism isn’t making us objectively better off or happier. It’s impossible to separate consumerism from status, and status is a zero-sum game. For every winner, there must be a loser. And that means that, as a whole, status-seeking can never make us better off. We’re working ourselves to death to try and win a game that doesn’t improve our world. Why?

Advertising is the proximate cause. Somewhere along the way, advertisers realized that instead of trying to persuade people directly that this product would serve some particular need, you could bypass the rational argument and appeal to subconscious desires and fears. Doing this allows for things like “brand loyalty.” It also detaches consumption from need. You can have enough physical objects, but can you ever have enough contentment, or security, or joy, or peace?

So car commercials (to take one example) might mention features, but most of the work is done by stoking your desires: for excitement if it’s a sports car, for prestige if it’s a luxury car, or for competence if it’s a pickup truck. Then those desires are associated with the make and model of the car and presto! The car purchase isn’t about the car anymore. It’s about your aspirations as a human being.

The really sinister side-effect is that when you hand over the cash to buy whatever you’ve been persuaded to buy, what you’re actually hoping for is not a car or ice cream or a video game system. What you’re actually seeking is the fulfillment of a much deeper desire for belonging or safety or peace or contentment. Since no product can actually meet those deeper desires, advertising simultaneously stokes longing and redirects us away from avenues that could potentially fulfill it. We’re all like Dumbledore in the cave, drinking poison that only makes us thirstier and thirstier.

One commercial will not have any discernible effect, of course, but life in 21st century America is a life saturated by these messages.

And if you think it’s bad enough when the products sell you something external, what about all the products that promise to make you better? Skinnier, stronger, tanner, whatever. The whole outrage of fashion models photoshopped past biological possibility is just one corner of the overall edifice of an advertising ecosystem that is calculated to make us hungry and then sell us meals of thin air.

I developed this theory that advertising fuels consumerism, which sabotages our happiness at an individual and social level when I was a teenager in the 1990s. There was no social media back then.

So, getting back to The Social Dilemma, the problem isn’t that life was fine and dandy and then social networking came and destroyed everything. The problem is that we already lived in a sick, consumerist society where advertising inflamed desires and directed them away from any hope of fulfillment, and then social media made it even worse.

After all, everything that social media does has been done before.

Newsfeeds tweaked to keep you scrolling endlessly? Radio stations have endlessly fiddled with their formulas for placing advertisements to keep you from changing that dial. TV shows were written around advertising breaks to make sure you waited for the action to continue. (Watch any old episode of Law and Order to see what I mean.) Social media does the same thing, it’s just better at it. (Partially through individualized feeds and AI algorithms, but also through effectively crowd-sourcing the job: every meme you post contributes to keeping your friends and family ensnared.)

Advertisements bypassing objective appeals to quality or function and appealing straight to your personal identity, your hopes, your fears? Again, this is old news. Consider the fact that you immediately picture in your mind different stereotypes for the kind of person who drives a Ford F-150, a Subaru Outback, or a Honda Civic. Old fashioned advertisements were already well on the way of fracturing society into “image tribes” that defined themselves and each other at least in part in terms of their consumption patterns. Social media just doubled down on that trend by allowing increasingly smaller and more homogeneous tribes to find and socialize with each other (and be targeted by advertisers).

So the biggest thing that was missing from The Social Dilemma was the realization that social media isn’t some strange new problem. It’s an old problem made worse.

Solutions

The final shortcoming of The Social Dilemma is that there were no solutions offered. This is an odd gap because at least one potential solution is pretty obvious: stop relying on ad-supported products and services. If you paid $5 / month for your Facebook account and that was their sole revenue stream (no ads allowed), then a lot of the perverse incentives around manipulating your feed would go away.

Another solution would be stricter privacy controls. As I mentioned above, the biggest differentiator between social media and older, broadcast media is individualization. I’ve read (can’t remember where) about the idea of privacy collectives: groups of consumers could band together, withhold their data from social media groups, and then dole it out in exchange for revenue (why shouldn’t you get paid for the advertisements you watch?) or just refuse to participate at all.

These solutions have drawbacks. It sounds nice to get paid for watching ads (nicer than the alternative, anyway) and to have control over your data, but there are some fundamental economic realities to consider. “Free” services like Facebook and Gmail and YouTube can never actually be free. Someone has to pay for the servers, the electricity, the bandwidth, the developers, and all of that. If advertisers don’t, then consumers will need to. Individuals can opt-out and basically free-ride on the rest of us, but if everyone actually did it then the system would collapse. (That’s why I don’t use ad blockers, by the way. It violates the categorical imperative.)

And yeah, paying $5/month to Twitter (or whatever) would significantly change the incentives to manipulate your feed, but it wouldn’t actually make them go away. They’d still have every incentive to keep you as highly engaged as possible to make sure you never canceled your subscription and enlisted all your friends to sign up, too.

Still, it would have been nice if The Social Dilemma had spent some time talking about specific possible solutions.

On the other hand, here’s an uncomfortable truth: there might not be any plausible solutions. Not the kind a Netflix documentary is willing to entertain, anyway.

In the prior section, I said “advertising is the proximate cause” of consumerism (emphasis added this time). I think there is a deeper cause, and advertising—the way it is done today—is only a symptom of that deeper cause.

When you stop trying to persuade people to buy your product directly—by appealing to their reason—and start trying to bypass their reason to appeal to subconscious desires, you are effectively dehumanizing them. You are treating them as a thing to be manipulated. As a means to an end. Not as a person. Not as an end in itself.

That’s the supply side: consumerism is a reflection of our willingness to tolerate treating each other as things. We don’t love others.

On the demand side, the emptier your life is, the more susceptible you become to this kind of advertising. Someone who actually feels belonging in their life on a consistent basis isn’t going to be easily manipulated into buying beer (or whatever) by appealing to that need. Why would they? The need is already being met.

That’s the demand side: consumerism is a reflection of how much meaning is missing from so many of our lives. We don’t love God (or, to be less overtly religious, feel a sense of duty and awe towards transcendent values).

As long as these underlying dysfunctions are in place, we will never successfully detoxify advertising through clever policies and incentives. There’s no conceivable way to reasonably enforce a law that says “advertising that objectifies consumers is illegal,” and any such law would violate the First Amendment in any case.

Therefore, the one and only way to detoxify our advertising and social media is to overthrow consumerism at the root.

The difficult reality is that social media is not intrinsically toxic any more than advertising is intrinsically toxic. What we’re witnessing is our cultural maladies amplified and reflected back through our technologies. They are not the problem. We are.

Therefore, the one and only way to detoxify our advertising and social media is to overthrow consumerism at the root. Not with creative policies or stringent laws and regulations, but with a fundamental change in our cultural values.

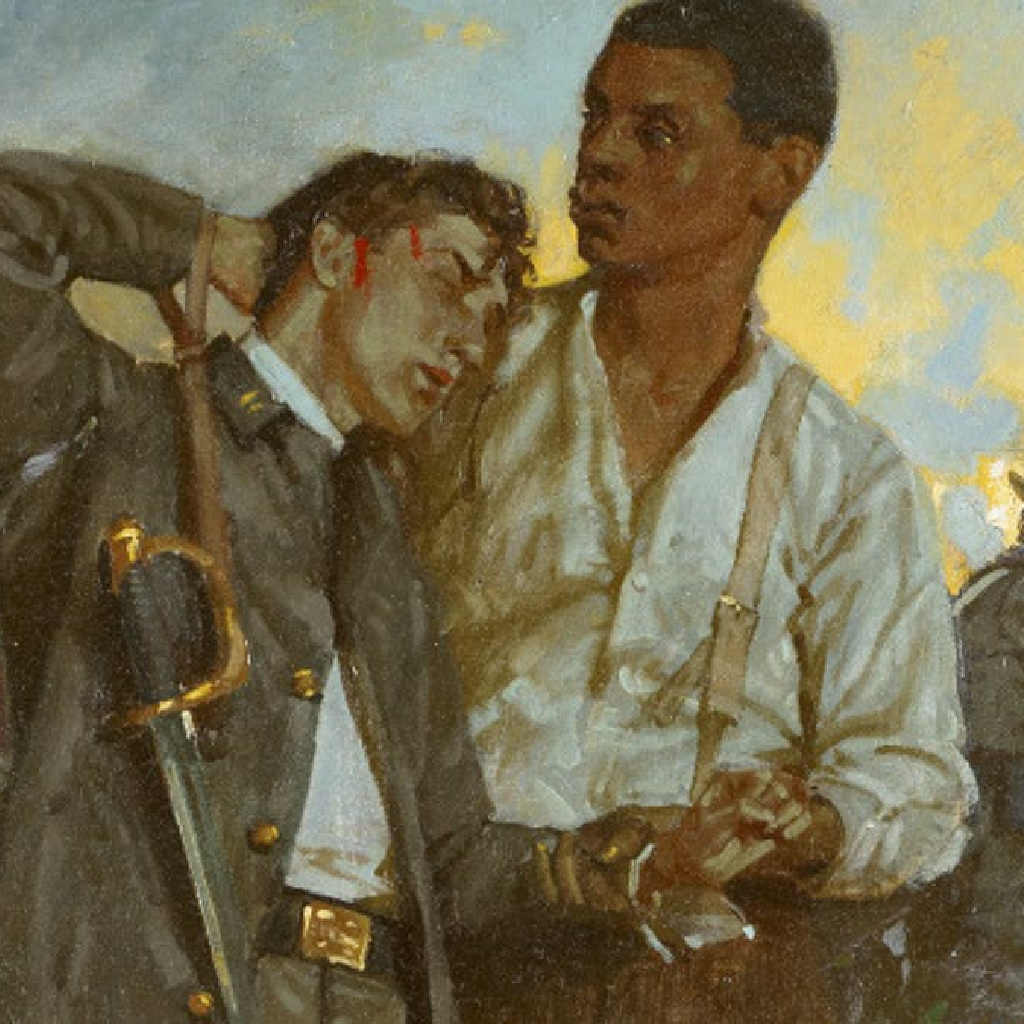

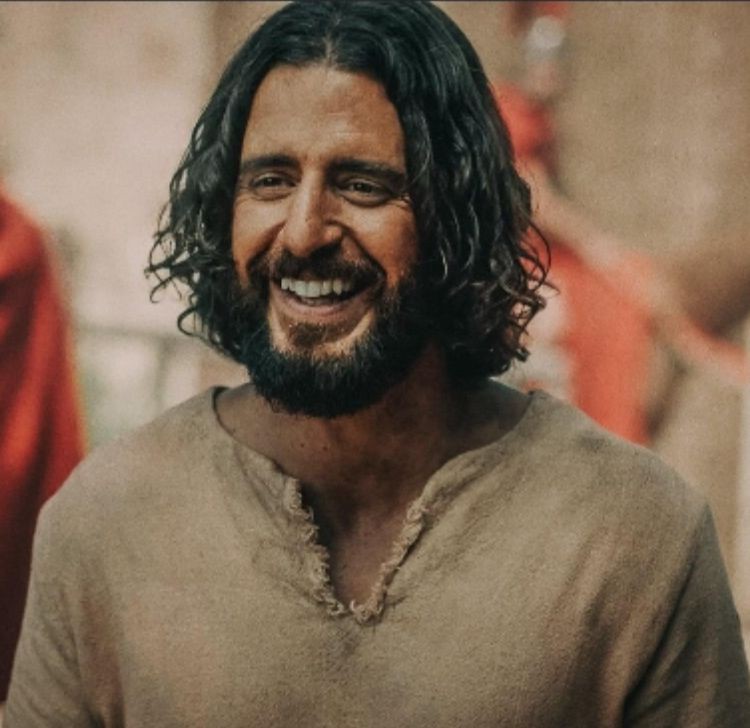

We have the template for just such a revolution. The most innovative inheritance of the Christian tradition is the belief that, as children of God, every human life is individually and intrinsically valuable. An earnest embrace of this principle would make manipulative advertising unthinkable and intolerable. Christianity—like all great religions, but perhaps with particular emphasis—also teaches that a valuable life is found only in the service of others, service that would fill the emptiness in our lives and make us dramatically less susceptible to manipulation in the first place.

This is not an idealistic vision of Utopia. I am not talking about making society perfect. Only making it incrementally better. Consumerism is not binary. The sickness is a spectrum. Every step we could take away from our present state and towards a society more mindful of transcendent ideals (truth, beauty, and the sacred) and more dedicated to the love and service of our neighbors would bring a commensurate reduction in the sickness of manipulative advertising that results in tribalism, animosity, and social breakdown.

There’s a word for what I’m talking about, and the word is… repentance. Consumerism, the underlying cause of toxic advertising that is the kernel of the destruction wrought by social media, is the cultural incarnation of our pride and selfishness. We can’t jury rig an economic or legal solution to a fundamentally spiritual problem.

We need to renounce what we’re doing wrong and learn—individually and collectively—to do better.