It was shaping up to be yet another remarkable, almost miraculous election week for Donald Trump. Leading in Georgia, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, North Carolina, and Michigan in the early morning hours (after having been significantly and consistently down in the polls in some of these states)—and with Texas and Florida wrapped up with a bow, President Trump had every right to be confident and to speak with more than a little excitement.

Instead of teasing a possible celebration to come, however, the President directed singular focus on the fact that no major network (including Fox News) had yet called these five battleground states as victories for him. Rather than expected complexities of what others had called a “fairly smooth election process,” President Trump insisted this delay was yet more evidence that something foul was afoot.

Even for those who had predicted the possibility of a premature declaration of victory, this was alarming talk.

“You know what happened?” He said, the Democrats “knew they couldn’t win, so they said, ‘let’s go to court’…and did I predict this? I’ve been saying from the day I heard they were going to send out tens of millions of ballots…either they were going to win—or if they didn’t win, they were going to take us to court.”

He concluded: “This is a major fraud on our nation” and “this is a fraud on the American public—this is an embarrassment on our country….Nobody has seen anything like it.”

The President went on to insist the election had already been won—“Frankly, we did win this election”—something presumably all Americans would have known if not for the “very sad group of people” trying to rob him of victory.

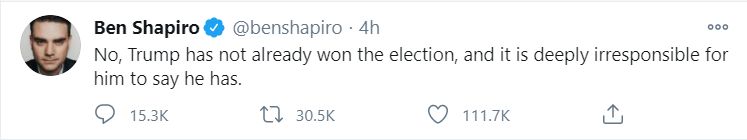

Even for those who had predicted the possibility of a premature declaration of victory, this was alarming talk. Even some of his strong supporters pushed back:

The assertions of election-day fraud were alarming, even for those concerned with prior accusations of a Biden victory coming only through a “rigged” election. After all, these claims of present fraud were arising not from a heartbreaking loss (that virtually everyone had predicted was coming); rather, they were directed at a fairly routine aspect of American elections—that it sometimes takes a few days for a final victor to be known.

Speaking of the delay in final results, one presidential historian, John Meacham, pointed out minutes before the President spoke, “this is not uncommon—almost half the time in our modern era since 1960, we have gone to bed without knowing who won. 1960, 1968, 1976, 2000, 2004, and 2016. This is not an anomaly.” This Pulitzer Prize-winning scholar later added:

There’s nothing outside the American tradition and the ordinary conventions of American history that says you have to know the winner by midnight on election night. For many, many times in our history, this has taken some time. And it’s the most vital decision we make in our country. This is our collective expression of the national will, in terms of who should be in charge of our affairs. Isn’t that worth a couple of days?

In fairness, there were some irregularities through the night—not unanticipated in an election with unprecedented numbers of people voting by mail due to fears of virus exposure through in-person voting. And I would argue it’s therefore not unreasonable for the leadership of either party to be concerned about the potential for novel (and real) abuse of mail-in ballot processes that are brand-new in so many states.

Neither is it fair to pretend that any desire to ensure ballot integrity and election security represents covert, sinister attempts at “mass voter suppression.” To the degree President Trump was motivated to ensure this kind of electoral integrity (especially amidst massive COVID-inducted changes in procedure), anyone who cares about the continued fairness of our elections should perhaps be sympathetic to the impulse.

But it wasn’t mere caution the President stood to deliver. It was a pointed, dark accusation against a vicious group of unnamed people who were “trying to disenfranchise” his supporters and “trying to STEAL the Election,” as he tweeted prior to his speech.

Even in the face of the plainest of realities (again, the simple need to finish counting votes after a record turnout), I find it remarkable how suspicion finds a way to conjure evidence of dark motives….and someone out to get us. As Ian Gibson once wrote, “a suspicious mind will see evidence of poison wherever it looks.”

In fairness, once again, it’s perhaps not hard to understand how President Trump comes away feeling this way— e.g., after years of trying to defend himself against massive accusations designed to take him down (including both fair and unfair critiques).

The President is also clearly not alone in modeling such suspicion. The rhetoric on the left over the last year has become even more pointed in making accusations across a variety of areas, but especially in terms of highlighting latent racial hostility in all directions. Indeed, it’s worth pointing out that the President’s own accusations of fraud are a mirror opposite of what others have leveled at Republicans for the last six months: they’re trying to rig the election in their favor!

Rather than talking about the surprisingly strong showing of President Trump last night, our collective attention will be absorbed in the darker insinuations of Something Sinister he raised.

In short: this hidden pandemic of suspicion and accusation goes far beyond the White House and the Republican party.

Infectious disease is more than a metaphor too since one accusation triggers another—with suspicion fomenting more suspicion, in a metastasizing mass. The ancient author of Proverbs describes strife (Prov. 16:28) and discord (Prov. 6:19) as something that can be “sown”—with bad seeds potentially spreading in every direction.

The evidence of seeds sown from that speech just a few hours ago is everywhere this Day After in America—in every newspaper, every workplace, and even many homes. Rather than talking about the surprisingly strong showing of President Trump last night, our collective attention will be absorbed in the darker insinuations of Something Sinister he raised.

As Dan Baltz noted, “Whatever happens in the vote count, whatever the courts do or don’t do, Trump has given his followers license to see anything other than a Trump victory as a stolen election.”

That kind of searing suspicion begets only more of the same. For instance, almost immediately after the President spoke, Rachel Maddow was quick to assert in response that the only reason he would make such accusations was because he knew he couldn’t win fairly—and had to resort to legal fights to try and steal the election (sound familiar?).

How will President Trump’s own core supporters respond to these dark accusations he raised last night? Surely many—even most—will simply believe them…adopting and absorbing them into their own frame of reference—in part, or in whole.

All this explains why the potential of spiraling accusations in such a volatile atmosphere is one of the scenarios experts had most feared for election night.

And our President did not disappoint.

How will the rest of America respond? That’s really my own big question: When does this level of pointed accusation and suspicion devolve into something far worse?

That same wise book of Proverbs compares a contentious man to “burning coals” and “fire” that “kindle strife” (Prov. 26:21). Speaking soberly after the President’s remarks, Chris Wallace noted the volatile situation in our country and suggested the President had just “thrown a match” on a smoldering fire.

How long will it be before the sparks from mounting suspicion and accusation all around us start a raging fire no longer in our control?

Central to the Book of Mormon’s own narrative account are warnings about precisely this possibility—and the disastrous consequences that can result for entire peoples.

The book also relays detailed and perfect instruction for those who want to avoid getting burned—and, in the other direction, who want to live a very different way and build a very different kind of society.

Answers exist to all these questions for those looking for them, as we’ve summarized in our recent reviews of Pastors on Politics and Prophets on Politics.

I pray that more Americans will find these answers—and receive them in their lives.

Joining us—and the many still hungry for peace in America—in finding a better way.