One characteristic of our contemporary American life is rhetoric on both sides of the political spectrum that paints a stark, black and white (or red and blue) picture of reality, positioning one group of people as fundamentally against another group: left v. right, rich v. poor, black v. white, gay v. straight, men v. women, etc.

Clearly, there are important issues to discuss across all of these meaningful differences—urgent questions with real-life, practical impacts on the well-being of people involved. We live in a time of growing income disparities, deepening racial animosities, and objectifying aggression against women. These issues call for the highest priority attention from everyone with concern and interest in promoting the well-being of the most vulnerable among us.

But who exactly do we think has that interest and concern? And what also does it mean to promote the well-being of individuals, groups, or society broadly?

That second question seems to be one about which we might have some sensible, even reasonable differences worth exploring.

Or maybe not. Perhaps the right answers to these questions are so clear and obvious that we ought to also be able to agree on who, in fact, is “compassionate” or “caring” as equally obvious. Do they have the right vision for social progress and advancement? Then, perhaps, they ought to be allowed space to speak candidly, to share online openly, to engage in academic discourse freely, etc. Otherwise, certain limitations probably need to be in place.

As strange as that might sound, that seems to be where we’ve arrived in America today.

When it comes to the well-being of women, for instance, a careful review of history compels any honest observer to confront the sad injustice and brutality that far too many women have faced for far too long—most often at the hands of men. This is not a statement “against” men; simply an acknowledgment of painful realities.

But there have also been many men and women over this same period of human history who have cared a great deal about the well-being, happiness and health of women. Although these individuals—both women and men—were united by a core commitment to improving lives, that has not necessarily meant they have always agreed on how to get there and the specific contours of what happiness entails.

And that’s just the point: thoughtful, good-hearted people have almost always disagreed on the exact means and the precise destination of social progress, even while they often genuinely shared the ultimate aspiration of improvement.

It’s more important that we remember this now than ever. Because it’s the opposite of what we’re hearing more and more.

If you raise critical questions or policy concerns about a proposal favoring a particular group, you might (or will probably be) accused of being “against” (or “the enemy”) of these same groups. Once we accept this as the de facto framing for political discourse, the core question becomes something like this: Are you for—or against—women? Are you for—or against—black people? Are you for—or against—gay people? Are you for—or against—poor people? Are you for—or against—sick people?

If we take for granted such a simplistic, adversarial framing, crucial nuance is inevitably lost, and so are opportunities to refine and improve policy proposals.

Is that the conversation we want to have in America? If so, let’s not be surprised if it becomes remarkably difficult to compromise or explore challenging issues with any degree of sophistication. Once you’ve shrunk the space of thoughtful disagreement between people who do care about the well-being of citizens of all stripes, it becomes predictably harder to pull off either community collaboration or political cooperation.

This has been evident in the larger American conversation about the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), which has been promoted by impassioned proponents as a common-sense effort to advance the rights, freedom, and equality of women. And that energy makes sense: amending the constitution is a serious and substantial step. And those who believe this step is crucial to the well-being of women in America have every right to make their earnest case.

But what of those who agree that women deserve equal rights, but disagree on what that looks like or how to get there? What about those who, perhaps, see this particular amendment effort as potentially harming the well-being of these same women?

As feminists, religious leaders, and other voices have again raised sincere concerns about possible implications—inadvertent or intended—of ERA’s passage, the response has been telling. After the Deseret News ran a respectful editorial opposing the ERA, Michelle Quist suggested that the editorial’s concerns were, among other things, “nefariously misleading.”

Really?

The Oxford dictionary defines nefarious as “wicked or criminal” as in “the nefarious activities of the organized-crime syndicates.” Synonyms include heinous, odious, vicious, vile, abominable, degenerate, depraved, monstrous, evil, treacherous, and villainous. Another person called the op-ed “garbage” and tweeted that it “stinks of systematic sexism.”

“Sound and fury,” to paraphrase Shakespeare, signifies “nothing” – except, perhaps, when it advances a particular cause or confounds that of our opponents.

Since when have we come to imagine that thoughtful men and women would somehow agree on how exactly to help support people who are struggling?

Once again, is this really the conversation we want to be having? Impugning the motives of people who disagree in a civil manner with a particular position?

There is another way. There is a better way.

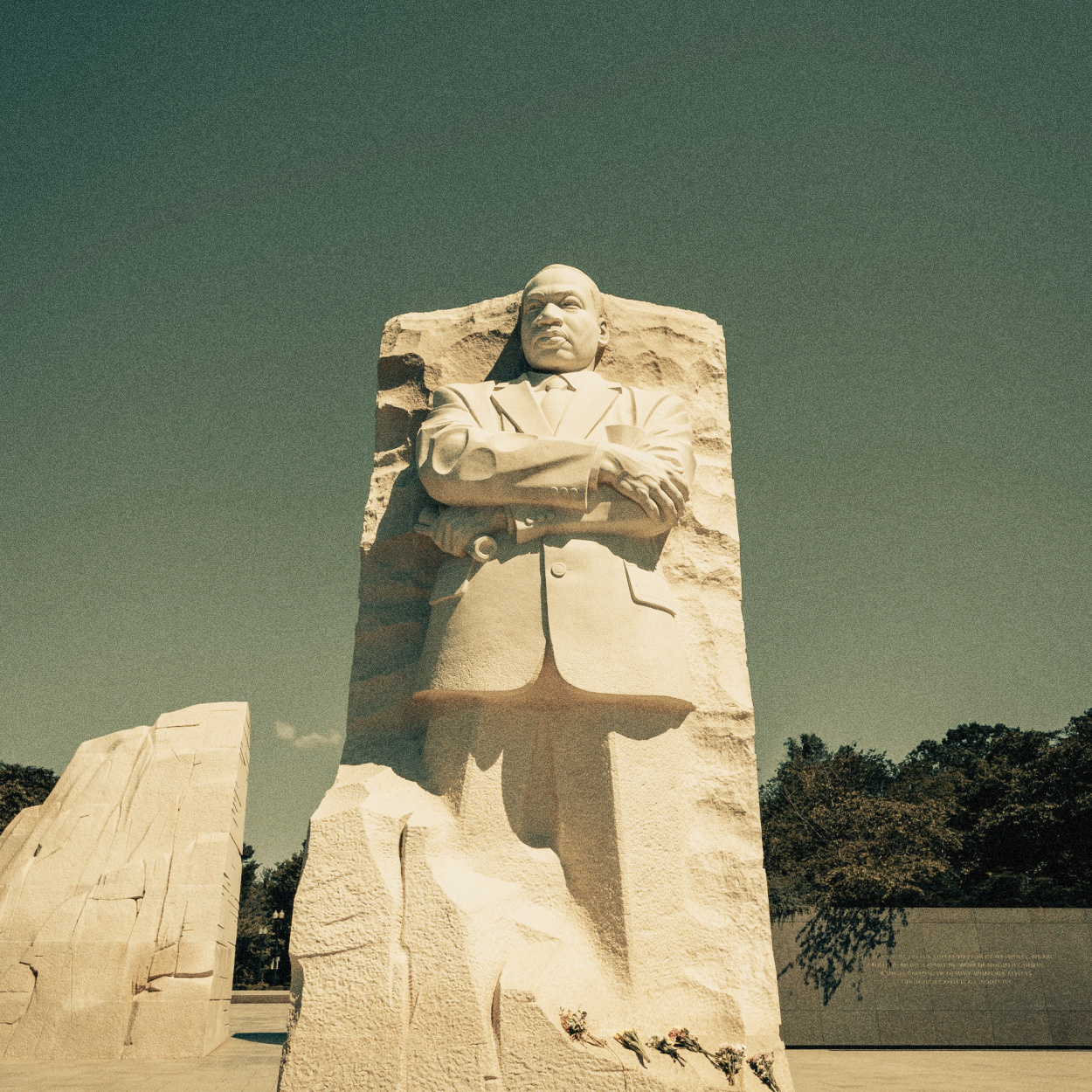

At the core of American pluralism is the (imperfect, but improving) effort to preserve robust yet civil disagreement among fellow citizens. Ours is a tradition of vibrant, rich, and productive ways of disagreeing that don’t involve so much needless animosity and aggression.

Precisely because these questions are so important, we believe it’s critical to preserve and expand our capacity to explore serious differences in how we approach the answers. The alternative—more aggression, pressure, force—won’t bring to pass genuine social progress, however you define it.

So, when it comes to race, gender, class, sexuality, and so many other important and pressing issues, let’s hear each other out—stretching our hearts and minds to consider ways we can come together, learn more, grow more, cooperate, and make compromises where possible. And when we still disagree profoundly, even vehemently, let’s do so as brothers and sisters, countrymen and women—without pretending that someone’s disagreement with us makes them a liar or somehow malevolent.

That’s just not true, in most instances. It might fire up supporters, but at the cost of amplifying an illusion about our political opponents.

Let’s do as the ancient poet Kabir once proposed and “just throw away all thoughts of imaginary things.”

However crazy or dangerous you might think the perspective of your political opposite is, there’s a pretty good chance they don’t think it’s crazy or dangerous—and even probably think it’s going to help improve things.

Just like you. Imagine that!