Thinkers, leaders, and scholars have noted the uniqueness of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ view of “restoration.” In his recent publication on Mormon theology, Terryl Givens, recounting the impact of Moroni’s angelic visitation to a young Joseph Smith, summarized this reality as follows: “In clarifying what this work would entail, Moroni turned Smith’s understanding of restoration inside out … Here is no simple paring away, no mere stripping back to essentials, but the prelude to a vast expansion” (p. 29). Indeed, a key characteristic of the Latter-day Restoration is the simultaneous reaching back to truths and organizations made known in a primitive past and an openness to ideas and structures which have not yet been revealed. Whether that work be the articulation of (re)revealed gospel truths, the provision of saving ordinances that link the entire human family, missionary efforts for the living and vicarious ordinance work for the dead, or the reestablishment of divinely inspired church structures, most official church discourse understands the “restitution of all things” (Acts 3:21) as embodied in the doctrines, aims, and activities of the Church itself.

Yet the Church’s bold claim to both historical precedents and a vast doctrinal expansion to historical Christianity—salvation and forever families, heaven and eternal progression, priestly authority and modern-day keys and ordinances—may still be too narrow a vision for what “the Restoration” seems to include. As bold as Latter-day Saint truth claims may be, I suggest that our scripture and teaching makes clear that the establishment of the Church (and all that entails)—which is what most contemporary members mean when they use the term “Restoration”—is only one small part of God’s “restoration” work. This does not mean that members must relinquish an appreciation for the “restoration of the true church.” Rather, my contention is that members have the opportunity to learn to re-see the restoration of the Church as nested within a grander, God-driven Restoration Project that includes Church truth claims, ordinances, and institutions, but which also include restoring physical bodies, communities, and, eventually, everything within the created cosmos. By more clearly seeing the Church’s role against this larger, cosmic restoration backdrop, we see that God’s restoration concerns include but also go beyond the restoration of God’s Kingdom as embodied by the teachings, ordinances, and activities of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. God’s work in restoring the Church is part of restoring all creation. I suggest when the Church of Jesus Christ’s vision of “Restoration” expands, members are freed to embrace a far more inclusive view of our temporal existence and are better able to understand how individual efforts, inside and outside church activities, are situated within God’s eternal creative and restorative efforts.

Current Restoration Language

In the Restoration Proclamation, we find the most succinct and arguably authoritative statement on how and what constitutes the Church’s official view of “the Restoration.” Though issued in commemoration of the 200th anniversary of the Church’s founding, its language is consistent with other contemporary statements on restoration. Generally, current (capital ‘R’) restoration language suggests “the Restoration” started in 1820 with the appearance of God and Jesus Christ to Joseph Smith. The restoration is generally considered to be inclusive of things such as instruction on important doctrines both directly to church leaders via revelation and through the publication of The Book of Mormon; the re-establishment of a specific church organization(s); the granting of authority to lead the Church and perform ordinances within it including specifically sealing ordinances; and the return of specific church offices and priesthood keys that have since been perpetuated to our current day. There is no doubt that, relative to other religious traditions, these assertions are bold. The Church makes unapologetic claims to doctrinal, organizational, ecclesiastical, and sacramental (capital- ‘T’) Truth and to a heavenly-mandated religious structure for all humanity. With the exception of the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches, whose claims are similar (though with different loci of authority), no other major Christian denomination of which I am aware makes such remarkable assertions. And, yet, once again, even accounting for the boldness of these statements, these claims may not go far enough. By narrowing the temporal scope of the restoration, the Church restoration language narrows the definition of what constitutes restoration.

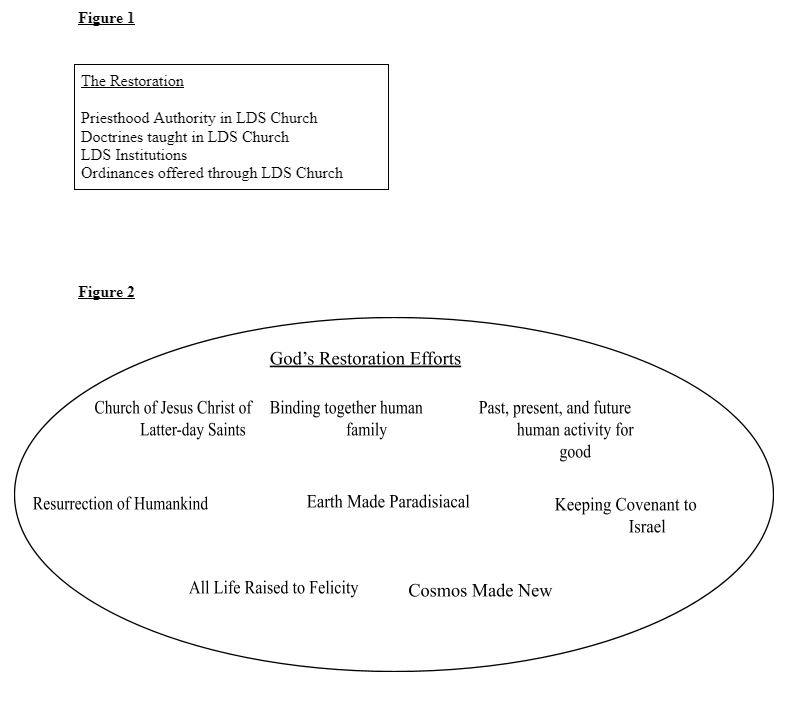

First, by narrowing the temporal scope of the restoration, the Church restoration language narrows the definition of what constitutes restoration. Keyed off an 1820 timeline, the proclamation defines “Restoration” to be constitutive of only those activities directly tied to the transmittal of specific doctrines and the establishment of particular religious structures/ organizations which occurred after 1820. Bounding the restoration to a timeline that expressly mirrors the Church’s incorporation expressly ties restoration to the Church institution itself: in effect saying, where there is no Church (or Church in the making) there is no Restoration. Second, and similarly, by the narrowing of geographic boundaries of restoration to the environs of Joseph Smith (and subsequent Church leaders), no human endeavor outside of Church-related activities, no matter how inspired, is considered to be, formally, part of the restoration; these efforts are relegated to prelude- or preparation-only. Third, and finally, by narrowing the restoration to a specific time and place (and, for all practical matters, institution) in human history there seems to be no space for God’s restorative work to include the larger, created cosmos. “Restoration,” according to its common contemporary Church usage, is solely and completely concerned with humanity. Indeed, created reality often feels like nothing more than an artfully constructed backdrop that is of secondary importance where restoration is concerned. We are left with a restoration excluding the sparrow, the lilies of the field, and the Milky Way. In sum, Church language about restoration can feel, in my estimation, somewhat anthropocentric (see Figure 1). Rather than envisioning a God that is always creating and restoring, Church restoration language can sometimes present God’s restoration efforts as narrowly focused on a specific time and place, and only concerned with one part of creation.

A Broader View of The Restoration

It is not accidental, I believe, that the term “Restoration” is used to describe the work that God undertook with Joseph Smith. The language of restoration resonates across the scriptural canon. Indeed, it is precisely because of its broad usage in scripture that I believe the term invites a careful reconsideration and a willingness to see restoration in a broader context. (Robert Matthews, in a Sperry Symposium presentation from 2004, suggested a variety of topics that ought to be included under the rubric of “restoration.” Many of his topics are tied to the LDS institution, but some, like the restoration of the earth, go beyond the traditional Church restoration rhetoric. Though I do not draw directly from Matthews’ work, it serves to underscore my central claim, that Church views of the restoration should include more than is usually identified).

I will explore a few of the ways that the language of restoration is employed in the Church’s scriptural canon, with a particular emphasis on Church of Jesus Christ-unique scripture where possible. The use of Latter-day Saint scripture is convenient as it was all originally transmitted in English, so it avoids translation complications. By uncovering some of the ways that this term is used, it becomes clear that—even in Latter-day Saint scripture—the restoration, from God’s perspective, goes well beyond truth claims and institutions.

Personal Restoration. In his April 2020 talk, Elder Garret Gong reflects on the way in which the term Restoration is used in the Book of Mormon. Gong notes that in the Book of Mormon the term is sometimes used to refer to resurrection, which is properly understood, says Gong, as a “physical restoration” and a “spiritual restoration.” Gong’s assertion is built on a close reading of Alma’s discourse to his son Corianton. In this discourse, Alma notes resurrection has a physical-restoration component: “the soul shall be restored to the body, and the body to the soul” and “every limb and joint shall be restored to its body… all things shall be restored to their proper and perfect frame.” Alma further notes that resurrection has a spiritual-restoration component: “the resurrection of the dead bringeth back men into the presence of God; and thus they are restored into his presence” (Alma 42:23). These two elements of personal restoration when taken together, are, in meaningful ways, part-and-parcel of the final judgment, which is also a restoration, whereby:

“all things shall be restored to their proper order, every thing to its natural frame—mortality raised to immortality, corruption to incorruption—raised to endless happiness to inherit the kingdom of God, or to endless misery to inherit the kingdom of the devil, the one on one hand, the other on the other… to be judged according to their works, according to the law and justice” (Alma 41:4; Alma 42:23).

Alma asserts that this personal restoration, accomplished by the Atonement of Jesus Christ, is one way in which “God bringeth about his great and eternal purposes, which were prepared from the foundation of the world” (Alma 42:26). Thus, Alma says, personal restoration is part of God’s plan from the beginning and something that God brings about for God’s purposes. Given that Latter-day Saint leaders lack the priesthood keys of resurrection, members must learn to re-see God’s restoration efforts as extending beyond the Church in this regard. Or said another way, the restoration includes resurrection, and this portion of the restoration is something on which God is engaged even though it is outside what the Church can accomplish.

Restoration of Israel. In 1831, Joseph Smith prophetically declared that God’s work would include the “restoration of the scattered Israel” (D&C 45:17). However, this was not a new idea, even in 1831. Joseph’s prophecy echoed many centuries’ worth of sacred text that all pointed to God literally and figuratively restoring Israel. In the Book of Mormon, Nephi expressly understood Isaiah to have spoken of God’s work with Israel as a work of “restoration” (1 Ne 15:20). Lehi quotes Joseph of Egypt to have prophesied concerning the work of God as encompassing a “restoration unto the house of Israel, and unto the seed of thy brethren” (2 Ne 3:4). Indeed, the pretext for the much-spoken-about “marvelous work and a wonder” is a desire by the Lord to “set his hand again the second time to restore his people” (2 Nephi 25:17). Israel will not only be restored spiritually but also physically and include, in some way, a return to lands previously promised.

Israel will not only be restored spiritually but also physically and include, in some way, a return to lands previously promised (Side note: Scriptural statements about Israel returning to its promised lands does not condone violence or any sort of ideology that justifies it. Israel’s return to lands in the Near East cannot ignore legitimate claims of the Palestinians, and violence against them risks doing to those people exactly what was done to the people of Israel in former times: forcible displacement. I do not offer a ‘model’ for how Israel’s land-based restoration will occur, and I believe any attempt to assert that scripture takes a clear position on this matter says more personal politics than it does to accurately represent scripture. I only note here that, alongside the likely-mythic conquest narrative of Joshua, the Old Testament also offers the far more practical [and likely more historically accurate] story of Judges whereby Israelite and Canaanite lived side-by-side. The restoration of Israel to lands in the Near East need not include the conquest or removal of the Palestinians.) While the Church of Jesus Christ may have a central role in the aspects of restoration that include ordinance work, it will likely have an extremely limited role in the other aspects of God’s work to restore Israel.

Restoration of this Earth. Modern-day revelation affirms that the earth itself will be restored. Echoing the words of John and Isaiah, Doctrine and Covenants asserts that when the “end shall come … The earth shall be consumed and there shall be a new heaven and a new earth” (D&C 29:23; Cf Revelation 21:1; Isaiah 65:17, 66:22). Lest there be any confusion, the 10th Article of Faith makes clear that it is this earth that “will be renewed and receive its paradisiacal glory.” This restoration will happen in a variety of ways. For instance, D&C 133 says that part of this restoration will include a coming together of the continents. Verses 23-24 read: “He [Jesus] shall command the great deep and it shall be driven back into the north countries, and the islands shall become one land, And the land of Jerusalem and the land of Zion shall be turned back into their own place, and the earth shall be like as it was in the days before it was divided.”

Doctrine and Covenants 63:21 says that “the earth shall be transfigured.” Section 130 takes this idea to its most dramatic conclusion; that revelation notes: “This earth, in its sanctified and immortal state, will be made like unto crystal and will be a Urim and Thummim to the inhabitants who dwell thereon, whereby all things pertaining to an inferior kingdom, or all kingdoms of a lower order, will be manifest to those who dwell on it; and this earth will be Christ’s” (v9). While it is unclear how and when this restoration will occur, God seems to be as concerned with restoring the Earth as with restoring humankind. As Joseph Smith stated, God’s work includes “salvation of the human family” and also “the renovation of the earth.” As was the case with physical/spiritual restoration of humankind and the restoration of Israel, restoring the Earth seems to be both part of God’s restoration efforts and well outside of the institutional influence of the Church of Jesus Christ.

Restoration of All Creation. God’s creations are without number (Moses 1:33; D&C 76:24). Neal A. Maxwell opined, “How many planets are there with people on them? We don’t know. There appear to be none in our own solar system, but we are not alone in the universe. We see the universe differently and correctly. God is not the God of only one planet! We see how the perspective we have is expanded dramatically by the revelations of the Restoration.” Given God’s care for God’s children (including of the apparent intergalactic sort!) it does not take much imagination to expand our perspective, as Maxwell suggests, to see that God’s concern, and thus God’s restoration efforts, extends beyond the human family. It was Jesus himself who spoke movingly of God noticing the loss of a single sparrow (Matt 10:29, 31; Luke 12:6-7). And, in fact, Latter-day Saint scripture states the opportunity of restoration is extended to all creation.

This occurs both generally and specifically. Generally, scripture asserts that “all old things shall pass away, and all things shall become new, even the heaven and the earth, and all the fulness thereof, both men and beasts, the fowls of the air, and the fishes of the sea” (D&C 29:24, emphasis added). And specifically, scripture states that by fulfilling the measure of its creation, all of creation—the earth, the heavens, humankind, animals, the earth, the heavens, etc.—can be “crowned with glory” (D&C 88:19, 25) and enjoy “eternal felicity” (D&C 77:3) (see also James E. Talmages’ Jesus the Christ, chapter 20). Creation is more than a mere backdrop to humankind’s restoration drama! Because, as Walt Whitman observed, “every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you … every atom of my blood, form’d from this soil, this air,” God is concerned with the restoration of all matter and thus God is actively working to restore humankind and all of creation along with it. Theologian Jurgen Moltmann explained it this way: “On the one hand, all human persons share in the same cosmic nature; on the other hand human hypostases exist with the community of all other created beings. It follows from the hypostatic bond between person and nature that if the person is redeemed, transfigured and deified, nature is redeemed, transfigured, and deified too” (pg 273). Thus, it seems, trees, plants, flowers, animals, insects, mountains, valleys, stars, and galaxies are all included in God’s restoration efforts. The explorer John Muir is said to have once asked, “is God’s mercy broad enough for bears?” (pgs 228-235). To that, Church scripture answers a resounding, “Yes! And broad enough for so much more.” Indeed, as meaningful as the restoration of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is, it seems to be an important, but small part (comparatively speaking) to God’s cosmic restoration activities. By seeing the restoration of the Church as one part of God’s larger Restoration activities, we can see God’s work of Restoration in places that we may not expect.

As a church, we have already begun to embrace a more expansive view of the restoration. Elder LeGrand Curtis Jr. writes in 2020 of the “ongoing nature of the restoration,” and in 2014, President Dieter Uchtdorf likewise taught the following in General Conference: “Sometimes we think of the Restoration of the gospel as something that is complete, already behind us. … In reality, the Restoration is an ongoing process.” I am suggesting that there is even more room to expand our view of what falls within the restoration rubric. However, perhaps there is concern by some that this approach to restoration will lessen or dilute the focus of important Church-related activities (e.g., missionary and temple work, ministering, etc.). My sense is that this concern, to the extent that it exists, assumes the items discussed above are not already part of the restoration. Yet, what I have tried to show is that Church scripture seems unequivocal that God’s restoration work includes, but goes beyond, establishing truth claims, building the Church structure, engaging in proselyting, and doing proxy temple work. I believe that by seeing and acting with this broadened vision, it may impact how we see and interact with other people and with creation itself—allowing us to be more effective and more involved participants in all of God’s restoration activities. Let me offer a few ideas for how this might look in terms of how we see the world, how we act in the world, and how we understand the Atonement of Jesus Christ.

By seeing the restoration of the Church as one part of God’s larger Restoration activities, we can see God’s work of Restoration in places that we may not expect. In his recent book, Patrick Mason suggests that members of the Church embrace what he dubs “particularism” by learning to see that different people and groups “are blessed [by God] with particular spiritual gifts” (pg. 46). My sense is that, consistent with the above doctrinal backdrop, Mason’s argument ought to be extended. More than simply the exercising of God-given spiritual gifts in parallel to the restoration, Church members should learn to see the efforts of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Martin Luther King, Mother Teresa, Rosa Parks, Hildegard von Bingen, the Dali Lama, Mahatma Gandhi, Bartolome de Las Casas, and myriad other well-known (and anonymous) people who have made a difference in their sphere of influence, as taking part in God’s work of restoration, each in their time and place. We can see these individuals as the Holy people that we “know not of” but which God has “reserved unto myself” (D&C 49:8). With this view, the entire human family becomes a potential partner in Restoration. We are thus no longer a human family divided into the restoration-haves and the restoration-have-nots. And, moreover, by seeing God’s restoration efforts even more broadly and recognizing that it encompasses, but goes infinitely beyond the human family, we can start to grasp overwhelming, knee-buckling love that permeates the entire created universe. Crickets and cicadas, rocks and rivers, bears and buffalo, fishes and birds in all their variety, ferns and giant sequoias—everything from galaxies to grains of sand will partake in God’s restoration. As Catholic theologian Elizabeth Johnson movingly put it, “… the evolving world of life, all of matter in its endless permutations, will not be left behind but will be transfigured by the resurrection action of the Creator God … the gospel is meant for every creature under heaven!” (pg. 191).

By placing the restoration of the Church within God’s larger Restoration activities, we are also suddenly free to act in partnership with God in new and exciting ways. This perspective resonates with Patrick Mason who made a strong case that when working with our fellow humans, restoration work can now include more than just missionary and temple work. It can include any work that seeks to overcome oppression and increase the ability for individuals to progress in their lives’ journeys (pgs 73-88). Certainly, gospel instruction could be part of these efforts, but we can see that restoration includes all of the activities outlined in Matthew 25:36-37: “… for I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me, I was naked and you gave me clothing, I was sick and you took care of me, I was in prison and you visited me” (NRSV).

Fighting food insecurity and domestic abuse, taking care of the sick and elderly, bringing solace to the outcast and the refugees, and so much more are also Restoration activities. And even more, once our view of restoration extends beyond anthropocentric concerns and into cosmos, members of the Church of Jesus Christ may be more empowered to embrace preserving and improving our world as another way in which we can be part of God’s restoration (See, for instance, LDS Earth Stewardship, which has explored some of these ideas: https://ldsearthstewardship.org/). Whether it be through acting on behalf of endangered animals, fighting pollution, protecting our world’s waterways, developing cleaner alternatives to environmentally damaging forms of production, or deepening our understanding and appreciation of the marvelous universe we inhabit, all of these activities can be accomplished in support of God’s Restoration of the cosmos.

Perhaps most importantly, however, this new view of Restoration helps us better understand the infinite scope of Jesus’ own restoration work. As President Nelson explained, “The entire Creation was planned by God. A council in heaven was once convened in which we participated. There our Heavenly Father announced His divine plan.” Though this plan has many names, it is called by Alma “the plan of restoration” (Alma 41:2), a point Dallin H. Oaks reaffirms. Through Jesus, everything was created (Mosiah 3:8, Moses 2:1; John 1:3; Col 1:16). And through Jesus, “creation itself will be set free from its bondage” (Romans 8:21 NRSV). As Paul asserted, “[Jesus is] the firstborn of all creation … and through him God was pleased to reconcile to himself all things, whether on earth or in heaven, by making peace through the blood of his cross” (Col 1:15, 20 NRSV). Thus, with this new view of the Restoration, we can better see that Christ’s cross reconciles all things, whether on earth or in heaven and that the “restitution of all things” means more than just the restoration of specific doctrines, institutions, or ordinances: it means, literally, the restoration of all things (Acts 3:21). With this new vision we see that God not only created all things through Jesus Christ but that God will Restore all things through Jesus Christ (1 Cor 8:6; Eph 1:9-10, 20-23; Heb 1: 2-3; 2 Peter 3:13; Jn 1:1-14; Rev 5:13-14, 21:1-5, 22:13). Though he may not have intended it this way, Dallin H.Oaks’ statement that “the theology of the restored gospel of Jesus Christ is comprehensive, universal, merciful, and true” takes on an added dimension of power when we see just how comprehensive and universal Jesus’s Restoration work actually is.

Conclusion

As bold as it is, current Latter-day Saint restoration language may not go far enough. The theme of restoration resonates through ancient and modern scripture. The Restoration Proclamation makes a compelling case for the unique act of restoration that began in 1820 in New York. And the 1820-restoration that has grown into The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has a critical place in God’s Restoration activities. But I’ve come to believe that God’s restoration efforts include so much more. God’s restoration efforts also include the restoration of individuals to their proper and perfect form in God’s presence, the restoration of Israel to their lands of inheritance, the restoration of the Earth to its paradisiacal glory, and the restoration of all creation (see Figure 2). I think these added insights about God’s restoration efforts will help members of the Church see a new power in our restoration claims when we understand and act according to the belief that “nothing will be lost, but everything will be brought back again and gathered into the eternal kingdom of God…the realistic consequence of the theology of the cross can only be the restoration of all things” (Pg 251, emphasis original).