Although it happened more than 30 years ago, many of us have watched Michael Jordan line up, lope, and then explode from the free-throw line, soar and then hammer home a slam-dunk contest winning marvel. In a later interview, Jordan said, “It may only be for a second, but it’s flying and I think other people wish they could do it.” Yes, we do. It’s called envy, and we’ve all got a little of it.

Many are familiar with envy as one of the “Seven Deadly Sins,” so how can envy be something that might help or even heal brokenness in the world? Let’s turn to another person who soared in a different way.

In 1985, Krister Stendahl, then Lutheran Bishop of Stockholm, stepped to the microphone at a potentially volatile press conference in Stockholm, Sweden, and “offered support for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints building a temple there, against which there was growing opposition.” In that watershed moment, when many of his own countrymen and parishioners were angry at the prospect of an “American” church planting their temple on Swedish soil, the wise and gentle Stendahl stood alone and not only called for tolerance, but expressed his own respect for some aspects of Latter-day Saint doctrine and practice and further urged all to leave room for “holy envy” and the honoring of beautiful elements in faith traditions other than their own.

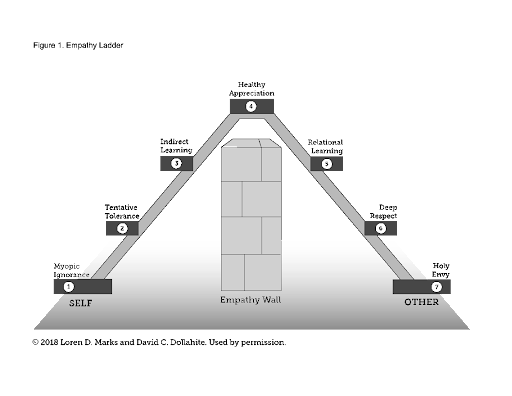

We concur with Stendahl, later Dean of Harvard Divinity School, that if we follow the better angels of our nature, we will seek ways to honor the best elements of other religions—indeed, that we will look with such depth and consideration that we will develop a little holy envy. We are also convinced that given the cultural climate in which we find ourselves in 2021, it has never been more important to seek to climb over what sociologist Arlie Hochschild (2016) has called “the empathy wall,” the wall that serves as a barrier to empathy for others.

One visualization of the willingness to identify with another person or social group is an “empathy ladder” that allows us to move from myopic ignorance to tentative tolerance, from tentative tolerance to indirect learning, from indirect learning to healthy appreciation, from healthy appreciation to relational learning, from relational learning to deep respect, and from deep respect to holy envy (see Figure 1 at end of article). We believe that one’s ability as a person to attain a deep knowledge of another person or group increases with additional steps on the empathy ladder. We also believe that multiple journeys to the other side of the wall enrich the mind, heart, identity, and sense of relationship and connection of the empathic person.

It is relatively easy to respect a person or group with whom you share similar political, social, religious, or artistic sensibilities. It is more difficult, but perhaps more honorable and socially meaningful to develop respect, and even holy envy, for a person or group with whom one may have significant disagreements. We believe that America needs many more people who are willing to pay the price to learn enough about other groups and persons who are very different from them in order to develop a deep respect and even a holy envy for aspects of their lives. This will enable the building of communities and a nation that fulfills the promise of the American motto E Pluribus Unum—from many, one.

For the past 20 years, we have shared the learning experience of a lifetime. We have met with diverse clergy across the Abrahamic faiths of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam and asked them to direct us to the most exemplary marriages and families in their respective faith communities. We then interviewed those families in their homes and asked them about their religious beliefs, practices, and communities. We asked them about their family relationships and how, in spite of myriad challenges, they had built a successful marriage and home. After our experience, we happily affirm our holy envy for families from each of the diverse groups we interviewed and for the faiths to which they are devoted. Below we share some of what we most admired about these families and faiths.

Jewish Families

In our in-depth interviews with American Jewish families, we found ourselves particularly impressed by the familial power of their sacred rituals. Specifically, in one study we identified Shabbat (the Jewish celebration of the Sabbath) as “the weekly family ritual par excellence.” We experience holy envy of this family ritual that has endured and been effectively adapted across millennia, in spite of the unspeakable persecutions the Jewish people have faced. Indeed, we have written a popular article to members of our own faith entitled “Making the Sabbath a Delight: Seven Lessons from Strong Jewish Families.” Further, perhaps no group has more carefully and intentionally converted the family dinner table into an altar or more effectively brought sacred ritual into the home.

A second point of pronounced admiration for us lies in what might be called academic and professional excellence. A disproportionate number of Jewish women and men we interviewed had attained terminal degrees in their selected fields (e.g., Ph.D., MD) and virtually all had completed some level of graduate education. This excellence was not merely a function of our sample. Although Jews comprise only 0.2% of the global population at approximately 13.85 million Jews worldwide, they enjoy disproportionate influence and excellence in many fields. For example, a late 20th-century study found that half of America’s 200 most influential intellectuals were Jewish and 76% had at least one Jewish parent. A more recent study noted that 22% of Nobel Prize winners were Jewish (Schuster, 2013). These exceptional contributions from a sliver of the population (0.2%) must be at least partly attributed to the foundation laid in Jewish homes. We experience deep respect and holy envy of both the rich religio-cultural foundation and the impressive results.

Asian Christian Families

Two unique features of our Asian Christians were that these families were (a) all immigrants to the United States (from mainland China, Japan, Korea, or Taiwan) and (b) adult converts to Christianity (some in their native land, some after immigration to the United States). Accordingly, one admirable feature of this religious-ethnic community that elicited holy envy from us was their courage to embrace change. These individuals and families literally crossed the globe and entered a new sociocultural world in search of their own vision and version of a better life. Most sought advanced education and/or employment that was rooted in a second or third language. Further, of these participant individuals and families who converted to Christianity, many made profound and often uncomfortable changes as they adopted a new worldview and way of life. The costs were, and some cases continue to be, substantial. Having embraced Christianity, however, these families have vigorously held to what they professed to hold dear. The sincerity of their conversions and their convictions was unquestionable.

No other Christian group we interviewed directly cited the Bible with more precision and accuracy. Further, few other groups manifested the level of pragmatic collectivism evident among Asian Christian churches. Examples of this included church members who literally met newly immigrating families at the docks and made extensive efforts to help them to culturally, religiously, and economically adapt to life in a new land. In spite of their high levels of education and learning, surpassed only by the Jewish families we interviewed, there was a sweetness, a sincerity, and a humility among the Asian Christian families that impressed us and even moved us. This humility often included gratitude to be living on American soil. When one realizes that in 1989, nearly half of these individuals were still living in China during the tragic massacre of the June Fourth Incident at Tiananmen Square, we are reminded of the precious nature of religious and political liberty that many Asian Christian immigrants to the United States embody.

Catholic and Orthodox Christian Families

The Catholic and Orthodox families we interviewed discussed the themes of unity and forgiveness with a texture and richness of their own.

Of the eight religious communities explored in this special issue, none (with the exception of Orthodox Judaism), featured the formality, structure, and level of ritual embodied in Mass and Communion (Catholic) and the Divine Mysteries (Orthodox Christian). Our participants helped us see the sacred intention behind the structure: the longing for unity—unity with God, with spouse (marriage is sacramental), with children (family is holy), and with sisters and brothers inside (and outside) the faith. We saw embodied in these faiths an explicit acknowledgment that these sacred unities were frequently disrupted by shortcomings, selfishness, and sin. This acknowledgment of human frailty and falling out, however, was met by the sacred and structured resource of confession to a priest (Catholic and Orthodox) and to family members (Orthodox). The forbidding of full participation to those who have not both confessed and forgiven (Orthodox) served as a fixed and structured motivation to humbly cleanse one’s heart of ill feelings in both formal and familial ways.

We find ourselves feeling respect and holy envy for the extensive and explicit efforts of the Catholic and Orthodox Christian faiths as they strive to replace guilt with hope, bitterness with forgiveness, divisiveness with unity, and animosity with atonement.

Black Christian Families

Eighty percent of the American Black Christian families we interviewed hailed from inner-city contexts. These were typically blue-collar families whose married status was often the exception on streets lined with single-mother families, poverty, and need. (For more detailed descriptions of these families, their strengths, and their struggles, see Marks et al., 2012). Selected themes from these families included (a) faith during difficult times: “The power of prayer gets us through,” and (b) “faith holds my family together.”

For these families, the United States is not a “post-race” nation. Poverty, often deep poverty, as well as unemployment, inadequate educational opportunities, discrimination, incarceration, and many other social ills were far too familiar to them and their loved ones. Further, these marriage-based families were often the first to receive “knocks of need” (requests for money, help, and even temporary housing) from the less fortunate who surrounded them (Marks et al., 2006). Their lived religion was not a sanitized, upper-middle-class spirituality, it was a desperate, deep, and pleading faith of survival that, even as we approach the 2020s, still contains echoes of the mournful notes of the shame of American slavery. Theirs was not merely a faith that enriched or added meaning to life. Their faith was often life itself. While we cannot claim to envy the plight of one of the most discriminated groups in U.S. history, we do envy the profound depth of their living faith in and relationship with a God that heard and sustained them through poignant challenges; challenges that were and are ever-present for most of these families.

Evangelical Christian Families

Our data from the American Evangelical Christian families we interviewed featured several strengths. Some of these overlap with other religious-ethnic communities (i.e., the importance of family unity and/or the cohesive nature of shared, sacred time together). Other strengths, however, were more distinct and pronounced. First, Evangelicals were the only group to mention faith community-based or promoted marital counseling so frequently that it was identified as a key finding (i.e., “seeking appropriate help outside of the marital relationship”). The Evangelical willingness to seek pastoral and professional help when marital help is needed, or even simply as a maintenance check-up, was laudable and instructive.

Second, all eight religious-ethnic communities we studied are people of the Book who honored the Hebrew Bible or Old Testament. Even so, perhaps no group referenced scripture so frequently and pervasively as Evangelical Christians or so intentionally and consistently turned to the Bible as the text of both first and final authority. Of particular emphasis were Proverbs 31 (“Who can find a virtuous woman?”) as a template for wives and mothers. Similarly, select Pauline epistles (“Husbands love your wives as Christ loved the church and gave Himself for it,” Ephesians 5:25) were a source of reference or “charter” for husbands and fathers. In connection with this latter reference and other similar passages, Evangelical spouses/parents strived to embody “servant leadership” in their marriages and families, an ideal that combined humility, service, and a willingness to sacrifice for others. This effort was, in many families, sufficiently earnest that it garnered our deep respect and holy envy.

Muslim Families

The American Muslim families we interviewed claimed more than half a dozen nations as their countries of nativity, making this religious-ethnic community the most international in our American Families of Faith project, serving as a reminder that this rapidly expanding faith is a growing global force. For some, this thought yields fear. Our experience was that many of the families who shared their homes and stories with us were of a quality of character that any nation might welcome. Their relationships seemed structured but strong; hierarchical but warm. Indeed, the structured hierarchy of Sharia, seen as oppressive by many, reportedly brought clarity of roles, complementarity, and harmonized vision for many of these families.

Islam reportedly served as a means for strengthening the family as a whole by encouraging respect and fostering understanding among members of the family. It seemed that the roles of individuals in the family, as taught in Islam, offered a sense of stability in family relationships. Further, the familial processes, shared devotion, unity, and celebration around the month-long fast of Ramadan elicited joy, even an ebullience, from Muslims of various ages.

The discipline of the month-long fast supplemented by zakat—a charitable offering of 2.5% of one’s wealth as an effort designed to relieve the suffering of the poor whose involuntary fast is constant. Ramadan and zakat are practices without precise parallel among the faiths we have studied. Indeed, if this level of generosity were practiced by all Muslims and by all privileged members of the human family, world hunger might be eradicated in short order. Indeed, the lived principle of zakat stimulates not only a sense of deep respect and holy envy but also hope for a better world.

Mainline Protestant Families

The American Mainline Protestant families we interviewed, perhaps more than any other faith or denomination we explored, emphasized and discussed the belief that “God is love” (1 John 4:8). More specifically, many drew implicit and occasionally explicit attention to the two great commandments (see Matthew 22:36-39 and Mark 12:28-31) or core values of Mainline Christianity, succinctly summarized as “love God, love people.”

We frequently found ourselves inspired by devout Mainline Christian families’ efforts to live out these beliefs in pragmatic ways, first in their marriages and families and then by serving their sisters and brothers in God’s family. A focus for many was “to love their neighbors as themselves.” Many Mainline Protestant Christians believe in the transforming power of God’s love through the Holy Spirit that enables humans to love others more deeply. A beautiful example of this, not shared in the article, came from a Mainline Protestant mother who discussed how her husband took their son to a soup kitchen each Saturday where together they served food to persons that were homeless. She spoke in glowing terms of the effect this had on their father-son relationship, illustrating their progressive approach to religion that emphasized social justice and care. We were inspired with holy envy by similar examples of shared practices that may not be explicitly “religious” but that were both relational and sacred.

Conclusion

In our nearly two decades of experience with the American Families of Faith research project, we have cherished the shared experience of coming to know a diverse community of religious families. We have entered and been graciously received in synagogues, mosques, churches, and chapels and have spoken with, worshipped with, interviewed, and been taught by numerous rabbis, imams, pastors, priests, and bishops. These (often overworked and typically generous) clergy entrusted us to interview the most devoted and strong families that their communities had to offer. As we did so, our tolerant interest and healthy appreciation became deep respect. In time, our deep respect became selective holy envy.

Some of the experiences shared with us were religiously and relationally sacred. Births, deaths, marriages, transcendent experiences, heartbreaks, and challenges were all poured out at different times. We came to know of these families’ strengths and of their struggles and we have written of both (Dollahite et al., 2018; 2019; Marks et al., 2019). In the final analysis, as a result of repeated journeys over the empathy wall, we find that we have been changed. We have been changed as researchers. But also, we want to be better husbands to our wives, more devoted and responsive parents, more dedicated helpers to our sisters and brothers in the human family, whether of our faith community or not. What we have learned from these families, in their words and in their homes, has resulted in holy envy—and this holy envy has yielded a better world.

If you like listening to audiobooks and podcasts, we have recorded a set of conversations about the families we interviewed that includes additional quotes from mothers, fathers, and youth, more of our experiences in attending their services, as well as personal experiences with friends of other faiths. These podcasts are available at: