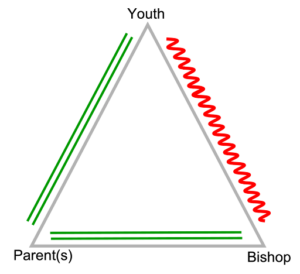

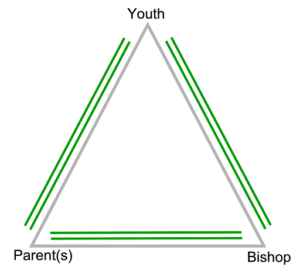

Some parents are kept from such enhanced ministry only for the lack of mentoring and support. Beyond establishing and sustaining open lines of communication, bishop–youth–parents relationships also provide an opportunity for collaboration and for youth–parents mentoring and mediation that directly supports covenant family relationships and helps establish them in loving Christlike ministry. Relationship therapists are widely familiar with relationship triangles and use their understanding to help them engage with and successfully mediate couple and family relationships. In the stories below, we conceptualize the bishop–youth–parent relationship as a relationship triangle to be carefully navigated. In the graphics, a straight green line indicates confidence and positivity in a relationship, while a squiggly red line indicates strain or uncertainty in a relationship (sometimes there is simply a relationship to be established, sometimes there is a rift or rupture to be repaired).

A Little Bit on Being an Intermediary in Relationships

Ideally and ultimately, we envision a bishop, parents, and youth united, each engaging with the others as intermediaries—youth encouraging their parents, parents encouraging their youth, and the bishop building relationships of trust with youth and with parents and encouraging and strengthening youth–parents relationships. Our focus here is on the bishop as an intermediary. Understanding relationship triangles, mediation theory teaches the importance of three relational–spiritual virtues that define, illuminate, and guide patterns of engagement and mediation. Those three characteristics of engagement and mediation (in complex relationship triangles) are relationship, neutrality, and responsibility. These are described in detail in clinical scholarship. We envision a bishop, parents, and youth united, each engaging with the others.

Finn’s Experience: Parents–Youth Strengthening the Youth–Bishop Relationship

Finn is about to turn 18 and wants to serve a mission. As depicted below, Finn is very close with his parents but anxious and ambivalent about his relationship with his bishop.

Several months ago, Finn shared with his parents that he is struggling with viewing pornography. Finn and his parents developed some practical strategies and spiritual protections to help him. Finn no longer sleeps with his phone in his room, and he only uses the internet in safe family spaces. Finn is continuing to pray, read scripture, serve others, and work at school, home, and his part-time business. Finn is actively striving for change behaviorally and spiritually, and his parents are fully present and available to him.

Finn’s parents express their confidence in the bishop and encourage Finn not to be fearful about moving forward with his repentance ecclesiastically. They have shared with Finn that meeting with his bishop can unlock keys for repentance. Finn agrees to meet with the bishop as long as his father comes with him. Finn’s dad steps into the bishop’s office for a moment immediately after church and expresses his and his wife’s confidence and support. Finn’s dad reports how important it likely is for the bishop to take some time to build a trusting relationship with Finn before broaching a worthiness interview. Finn’s parents share their desire and hope to work together in a sort of bishop–youth–parent council.

Although Finn’s heart is pounding, Finn is astonished to find that the bishop responds to his admission of his struggle with pornography in a kind and loving way. The bishop listens carefully, commends Finn for reaching out to his parents and his parents for their efforts, and suggests that Finn and his parents continue to work together and that all of them meet together about once a month or so. The bishop describes and delineates his ecclesiastical role and confirms and affirms Finn’s parents in counseling and supporting Finn in his repentance striving.

The bishop encourages Finn to participate fully in church and other strengthening experiences. The bishop shares with Finn and his parents principles that guide his ecclesiastical decisions and invites Finn’s parents to help Finn apply the principles, be accountable to developmentally appropriate expectations, and involve the bishop in all ecclesiastical aspects.

The bishop assures Finn that although pornography use is a significant spiritual–moral concern, it is a common developmental struggle. All agree to focus on virtuous desires, spiritual striving, and patient progress. Finn’s parents are relieved when the bishop suggests that Finn let go of the pressure of mission worthiness and focus on moving forward in life, including with college or vocational education and employment, believing that building a productive, rewarding life will strengthen him. Finn and his parents are invited to study together a book about the developmental challenges of the teen years and how they can respond to them. Walking out of the meeting, Finn is amazed that he held onto so much stress and anxiety when there wasn’t anything to fear after all.

Finn’s parents are able to be a helpful go-between, facilitating and supporting Finn’s growing relationship with his bishop. Finn’s parents are intentional in their support of Finn’s relationship with the bishop, especially when a misunderstanding could lead to a rift. Additionally, they feel blessed tremendously as they observe how the bishop counsels with Finn. In turn, the bishop feels helped by the support he receives from Finn’s parents and their observations, discernment, and wisdom concerning their son. In a way, the back-and-forth seems to offer a sort of mutual magnifying influence. As they work together, their relationships, confidence, and trust only grow stronger. Finn, too, feels that both his parents and bishop have “got his back,” and when any minor bumps are encountered, with support and collaboration all around, they are navigated successfully.

The bishop and parents counsel together, mentor one another, and respectively help mediate bishop–youth and youth–parents relationships. United, they help Finn seek out strengthening experiences and ground his repentance striving on a foundation of good activities and virtuous influences (see 1 Thessalonians 5:21). Finn feels surrounded and supported by Christ’s pure and perfect love at home and at church.

Ryan’s Experience: Blessings of Bishop–Youth–Parent Fellowship and Unity in Purpose and Counsel

Ryan is a 16-year-old junior in high school. In Ryan’s case, positive relationships and cooperation all around highlight the potential blessings of a bishop–youth–parents collaboration, united in purpose and counsel.

Ryan was recently asked out to a school dance—his first date—by his best friend Megan. At the dance, Megan pulled Ryan into a close embrace, and now Ryan feels guilty about the passions that it stirred within him. Ryan wants to talk with his parents,

Ryan’s parents discern his pensive mood, and while working on the car with Ryan, his father asks if everything is alright. After hearing Ryan’s experience, Ryan’s father is confident that parental counsel and support would be enough here, but he senses his son’s anxiousness concerning priesthood and temple privileges and defers to his son’s perceived need for ecclesiastical assurance. Ryan’s mother and father also believe it can be a good opportunity to strengthen Ryan in ecclesiastical relationships. Ryan’s father asks if he can give the bishop just a bit of a heads up, not on the particulars, but on the feelings he’s experiencing and his interaction with his parents thus far. Ryan agrees.

Ryan’s parents do become a bit anxious, hoping they and the bishop will be on the same page, but are committed to honoring ecclesiastical roles and fulfilling their covenant role as parents. The bishop, Ryan, and his parents decide to all meet together.

In spite of his preparation and this groundwork, when Ryan begins to share his experience, he breaks down crying, overcome with emotion, embarrassment, and the guilt typical of a spiritually zealous, perfectionistic teenager. The bishop and Ryan’s parents comfort Ryan with perspective and reassurance, together with commendation of his spiritual desires and aspirations. Ryan’s parents comment that the feelings Ryan experienced at the dance are understandable. The bishop suggests that he can learn from this experience the importance of avoiding stirring sexual feelings outside marriage. The bishop shares a spiritual impression and counsels Ryan to find a time for his parents and him to be in the temple together and then to all meet together again in a few weeks to talk about their temple experience and how Ryan is feeling then.

Ryan is in a blessed position where he is loved and supported by his parents and bishop, who are united in Christlike purpose and ministry. Ryan’s parents maintain respect for the bishop’s ecclesiastical role and stewardship, and the bishop is fully supportive of Ryan’s parents in their covenant family relationships. The bishop and Ryan’s parents counsel together, mentor each other in relating with Ryan, and support one another, mediating their respective bishop–youth and youth–parents relationships as needed. Setting an example of respect for the priesthood authority and keys the bishop holds invites the Spirit’s help to their collaboration and leads all to feel trusting, closer, and united.

The bishop and parents share the opportunity to communicate openly and to invite and encourage Ryan to fully involve each of them. As we discussed in Part 2, there will be scenarios where the bishop and parents might not agree on the best course of action for the youth, or where parental protectiveness could become a barrier to priesthood counsel or correction. Meekness, humility, and submission to the Spirit will be necessary as the bishop and parents mentor one another in working with Ryan and mediate on behalf of positive relationships.

Discussion—Uncovering Blessings in Home-Centered, Church-Supported Ministry

An informal bishop–youth–parents council and collaboration can be an inspired organic development. In each one of the fictional stories we’ve shared in this three-part series, the youth would benefit from a bishop–youth–parents alliance. Ideally, each of these youth would never have to confront discord, disunity, or conflict in any of these vital relationships: parents–youth, bishop–youth, parents–bishop.

Yet there may be times where youth will triangulate either with their parents or the bishop, testing the bishop’s and parents’ resolve to remain united. Or, one can imagine a situation where parents meeting with the bishop, or all meeting together, find they disagree on a best path forward. That’s when understanding boundaries of stewardship and authority becomes very important, and where it is vital to prayerfully invite the influence of the Spirit, lest a rift develop. Still, this is no different and likely less problematic than where bishops, parents, and youth do not counsel together and differences and disagreements develop through secondhand telephone-game communication with teens caught in the middle and relationships compromised. Unity and commitment can remain strong as bishops, parents, and youth remember the real risk when the Adversary is allowed to drive a wedge anywhere in the bishop-youth-parents system. Reconciliation is the most beautiful part of the gospel plan.

The new allowance for parents to accompany their child in ecclesiastical interviews provides comfort, assurance, and protection to youth, parents, and the bishop, as well as to their relationships. In addition, some bishops, parents, and youth may serendipitously discover wonderful, powerful, heretofore untapped opportunities to strengthen and magnify the divinely endowed, covenant parent–child relationship for supporting repentance striving and growth, with peace, hope, and joy through faith in Christ. Some Bishops may feel inspired in these opportunities, possess the confidence, and develop the comfort to pursue them with some families. Potential positive outcomes are imagined below:

- naturally allow for conversations whereby bishops and parents both understand their respective roles and boundaries and commit to support and sustain one another

- open and enhance lines of youth–parents communication, including through modeling and coaching compassionate parental ministry to their child

- soften, counsel, and strengthen the youth–parents relationships for supporting and helping, not hindering repentance

- provide gentle correction to parental ministry—engagement, processes—thereby enhancing parental Christlike ministry

- capitalize on parental insight and inspiration to help the bishop better understand the child and developmentally fit repentance counsel, guidance, and expectations to the individual child

- through an informal bishop–youth–parents council, discover in the diversity of perspectives the inspiration for counsel and action that is scattered among them

- be guided by the bishop and assist the bishop—who operates primarily in a context of Sunday ministry—as parents are able to discern daily their youth’s spiritual–emotional experience and help their child in regulating their responses to their challenges, seeking to achieve spiritually anchored emotional regulation—centering youth in inspired motivation for repentance, avoiding extremes of either apathy or toxic shame (See Alma 42:29)

- mentor and create shared opportunities for expressions of love, support, encouragement, and testimony of God’s infinite and inalienable love, youth’s divine nature, and Christ’s redeeming power through His atonement

- enlist family support (buy-in), provide opportunities for mutual sustaining of each other’s divinely appointed roles, help avoid misunderstandings that can occur in the familiar pattern of youth returning and reporting to parents how their interview went, and avoid rifts that can sometimes develop

- beyond examples in scripture of fathers and mothers counseling, blessing, and guiding their children for repentance, it is possible that through shared informal councils and counseling, the bishop can provide mentoring, live coaching, and encouragement, parents can provide insight and understanding, and youth can be supported

None of this is meant to create an expectation or burden or to place leverage or pressure on the ecclesiastical relationship. It is merely to suggest that parental attendance could naturally open the eyes of understanding and doors of opportunity previously unseen and unexplored. Some bishops may choose to visit with parents separately, either at first or throughout. Bishops, youth, and parents can ease into joint visits as readiness on the part of youth and parents (and the bishop) grows.

All this could be an element of enhancing spiritual self-reliance in the family and fulfilling President Russell M. Nelson’s call and counsel for home-centered, church-supported worship, gospel instruction, and ministry. Fathers and mothers can both be invited and inspired to more fully fulfill their covenant ministry in their family relationships. The family could be sustained as the fundamental covenant unit of which the Church of Jesus Christ is composed.

Still, some bishops or parents may reasonably feel that they lack the training, understanding, or temperament to navigate the complexity of the bishop–youth–parents relational system. Our intent is not to press youth, parents, or bishops to venture beyond their inspiration on how best to proceed. Such a family systems approach to ecclesiastical ministry can prove challenging, difficult, and labor-intensive—at first—and may seem burdensome, but it could ultimately reduce workload as parents are fitted to their covenant ministry and better support their child’s repentance and growth—and on a more frequent (even daily) basis than the bishop’s time allows. Bishop mentoring and mediation of youth–parents relationships can be as conceptually straightforward as understanding what positive, healthy interaction can look like and then inviting and coaching for it.

Conclusion

“Home-centered, Church-supported” is language invoking an opportunity that has always been present, accompanied now by an invitation that is at least implicit, if not explicit, for a transition away from exclusively individual counseling with ecclesiastical leaders to family relational counseling (and priesthood/ecclesiastical mentoring). The opportunity for ecclesiastical communication with, support to, and mentoring of the family as the fundamental unit of the Church and of eternity is abundantly and excitingly evident. We readily imagine both the challenge and blessings of bishops and parents envisioning and preparing for these kinds of win–win–win bishop–youth–parents engagements. Bishops, youth, and parents must all unite in building and sustaining these relationships. Bishops can express to youth and parents their profound commitment to and honor of the parents’ covenant family relationships and share their desire for mutual unity, support, and collaboration—thereby initiating, establishing, and growing these relationships long in advance of the need.

Is it worth the effort? We believe so. We anticipate the potential for abundant blessings—both anticipated and unforeseen—from bishop–youth–parents collaboration. In spite of some evident risks, reconciliation is the most beautiful part of the gospel plan and power in Christ, and with the Spirit’s help, never beyond reach.

Surely, peace, unity, and harmony in the bishop–youth–parents relationships are vital and will invite the companionship of the Spirit, the blessings of heaven, and promote successful spiritual cooperation and collaboration. There are abundant resources to assist in learning patterns of peacemaking encouraged by the prophet. Differences need not produce discord which, if ignored or if stirred into anger, can lead to brooding and festering on the one hand or contention on the other, either of which distance or drive away the Spirit. Disunity and discord sap bishop–youth–parents relationships of their full potential and can lead to serious rupture. The spiritual risks are significant.

Yet the spiritual potential in successfully establishing and navigating bishop-youth-parents relationships is tremendous. Thus, anxious, worrisome, painful, and difficult feelings that arise in the context of disagreement ought to be a useful invitation to strengthen relationships through engaging in a spirit of Christlike love and unity of heart, mind, and purpose. As pain is to the body—a vital signaling system—so our feelings are to our relationships—they tell us we have work to do. Anger is one of our natural feelings that signals trouble, yet it can be bridled, turned toward benevolent, relationship-focused repair attempts, and lead to reconciliation that then resumes successful focus on supporting and helping our youth. As we commit to our bishop–youth–parents relationships and as we remember the emotional–relational virtues that produce and predict successful engagement—relationship, neutrality, and responsibility—any rifts or ruptures can be turned into building blocks of enduring helping relationships.

While initially, the investment and commitment required of bishops, youth, and parents is significant, with humility, sensitivity, and mutual respect and with all eyes fixed on Christ, the blessings that come from mentoring eternal family and priesthood relationships are immeasurable and eternal. Also, it can ultimately reduce the load shouldered by the bishop. Each of these relationships, youth–parents, bishop–youth, bishop–parents, is important in its own right and well worth the investment. As parents and ecclesiastical leaders grow in their callings, confidence, and capacity, we can anticipate that they will neither be intimidated by nor shy away from these opportunities but rather enthusiastically embrace them, preserving and greatly magnifying their power and potential to help.

Could venturing an informal bishop–youth–parents council, counsel, and collaboration be a part of the ongoing Restoration and another “means [by which] the Lord can bring about great things”? Even a small venture—a leap of faith, trusting in the Spirit to guide—might be a foray that plants a precious seed that, in process of time, bears abundant fruit.