On November 1st, many Latter-day Saints were overjoyed at the publication of a talk on activism given by Ahmad Corbitt of the Church’s General Young Men’s Presidency. The reason for the talk’s positive reception by myself and others was the clarity that Brother Corbitt offered to a very difficult issue: when—and how—to attempt to influence the Church.

As Jeff Bennion and I wrote recently, most long-time church members have a wish list of things we would like to see change in the Church: things we would like to see happen and things we would like to see stop happening. This “wish list” is a normal experience of participating in any organization and, when held in a healthy and generous way, is in no way a sign that we are headed toward apostasy. Some items on our wish lists are minor: think of small procedural changes in our church service, for example. But others are more significant, such as how we approach difficult passages of scripture or the recent change allowing for civil weddings closer in time to our temple sealings. Voicing concerns in ways that are both charitable and sustaining is a constant threading-the-needle challenge for converted Latter-day Saints.

Years ago, I had a friend who worked in turning around companies, and one of his basic techniques was to ask people at all levels of a company, “what are the stupid things that we do?” and then he would enlist company personnel in methodically addressing the items on the list. That approach can obviously be risky: what one person considers a stupid organizational process, another person might consider a helpful and effective way of working. And when people have participated in developing processes, the labeling of those processes as “stupid” can feel personally hurtful and perhaps inadvertently contribute to a climate of excessive critique or complaint.

For these and other reasons, in most organizations, change is hard. It can be messy and divisive. In the Church of Jesus Christ, the way we approach advocacy for change is even more important to consider because the stakes are different. Brother Corbitt conveyed this very well, teaching that activism toward the Church “… diminishes faith in Christ and trust in God indirectly. Its pattern is to first undermine faith in Church leaders.”

In his remarks, Brother Corbitt was challenging some very basic assumptions about activism that are held by increasing numbers of church members in our secularizing society, particularly 1) members who have never worked to facilitate organizational change management; and 2) members who have adopted Marxist and other secular lenses for viewing problems and activism.

Latter-day Saints like myself understand those lenses toward the world and reject them, yet we were also challenged by Brother Corbitt’s talk in other ways: many of us also tend to fall into traps of counterproductive activism, and this happens when we operate within the drama triangle.

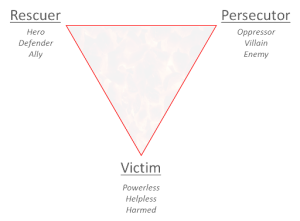

In 1972, Stephen Karpman published a graduate school paper, Fairy Tales and Script Drama Analysis, that drew upon his interest in acting and stories to propose a new way of visualizing some of our tendencies toward interpersonal conflict. Karpman suggested that in conflict, we often assume one of a set of roles in a predictable story played by three characters: persecutor, victim, and hero. These characters operate in a drama triangle that reinforces conflict and causes people to see each other as one-dimensional characters acting out a script.

An easy observation with the drama triangle is that if we frame the world in terms of these three basic roles, we will always see ourselves as either victims or rescuers, and we will always see people with whom we disagree as performing the role of the persecutor. This triangle presents a powerful story, a flattering one that validates our narratives of victimhood or fuels our self-righteous sense of heroism as we stand up to persecutors on behalf of victims.

Many theorists have explored the drama triangle for decades and have expanded upon it to generate some very useful insights into how people interact and how they can interact better. Some insights are readily apparent: First, activists and others who view themselves as performing the rescuer role often fall into patterns of narcissism and/or enabling. Codependency is a behavior that is immensely destructive to human development, and it is common among people who crave the emotional feedback of the rescuer role.

Another problem with the rescuer role is that some of the very worst human behavior throughout history has taken place among people who have envisioned themselves in that role. Most tyrants in the modern era have framed their horrors in terms of fairness, equity, and even benevolence. To offer one especially heartbreaking example, the Khmer Rouge was responsible for deaths estimated at up to one-quarter of Cambodia’s population, and movement leader Kheiu Samphan recently said of his motives: “… I have never wanted anything other than social justice for my country.”

A second set of insights relates to the victim role. In recent decades, plenty of commentary has addressed the problem of victim identity: Charlie Sykes’ A Nation of Victims was written in 1993, and more recently, Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff’s 2018 book The Coddling of the American Mind explored the perverse incentives of intersectionality and its expansion of the sense of victimhood on college campuses. Haidt and Lukianoff further discuss cognitive behavior and how cognitive distortions like black-and-white thinking and emotional reasoning reinforce this victim mentality. One of the most cogent insights in their book is their discussion of the locus of control. The internal locus of control—a sense that we are empowered to improve our own lives—is stifled by narratives of victimhood. This is true whether or not those narratives are based in reality.

The drama triangle is a toxic story we tell about ourselves and others, and though Karpman’s use of the term drama connotes playacting, it also expresses the personal appeal of the triangle. When we sense a lack of meaning in our lives, we sometimes try to fill that void with intense performative conflict: in a word, drama.

Much of the frustration with Brother Corbitt’s talk stems from the fact that he was speaking from the standpoint of Christianity, which only exists outside the drama triangle. And when people speak from outside the drama triangle, their insights simply cannot be understood or appreciated by people within the triangle. The drama triangle has its own vocabulary; it is enemy-oriented, and its goals are blame and shame, not redemption. Even the most wonderful, transcendent insights outside the drama triangle are mischaracterized as “harm” or “gaslighting” by people stuck inside it. But all of scripture and sacred history show us a plain choice between the drama triangle and God’s celestial paradigms.

As public criticism of the Church and the followers of Christ continues to increase, we can benefit from following the examples of many theorists who have responded to the drama triangle over the years. Some of them have suggested breaking out of the triangle by rethinking the roles: for example, challenger instead of persecutor; teacher instead of rescuer; creator instead of victim. Stepping outside the drama triangle is a process of accepting empowerment and shifting to an internal locus of control.

Brother Corbitt invited us to break out of the drama triangle by reminding us that activists—even activists who have caused real damage to the Church in recent years—are “friends,” “vigorously misguided,” and who have a “story of redemption.” For those of us with friends and family whose disillusionment and apostasy have been fueled by these activists, a transition to brother Corbitt’s charitable view might seem like an unattainable ideal. But I would encourage us to strive for that ideal. Charity is not just one of any number of equally-valid lenses for viewing the people around us: it is, in fact, God’s lens of reality itself. In pointing us toward charity, Brother Corbitt was fulfilling the challenging prophetic role delegated to him.