Years ago, the late novelist David Foster Wallace shared this little parable at a college commencement speech:

There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says, “Morning, boys. How’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes, “What the [heck] is water?”

Wallace explains that the point of this amusing story is “that the most obvious, important realities are often the ones that are hardest to see and talk about.” I would suggest that the Abrahamic covenant falls into this category: it’s the water we swim in, but it can sometimes be difficult to see or talk about how it relates to us today.

The Abrahamic covenant is foundational to the Old Testament. (In a sense it is the Old Testament since that title is better translated as Old Covenant.) And the Old Testament itself is foundational to literally every other scriptural text within the sacred canon within the Church of Jesus Christ. And yet, the Old Testament is arguably the most foreign to us. From a 21st-century perspective (particularly an American one), the Old Testament is a really weird book filled with the kind of sex and violence we’re typically encouraged to avoid consuming in the entertainment around us. It’s not always clear from a casual reading (or even an intensive reading with the King James English) what exactly is happening, who is involved, when it’s taking place, or the big question: why. This is especially true of the Abrahamic covenant. His hand of fellowship is continually extended, even though we tend to slap it away over and over again.

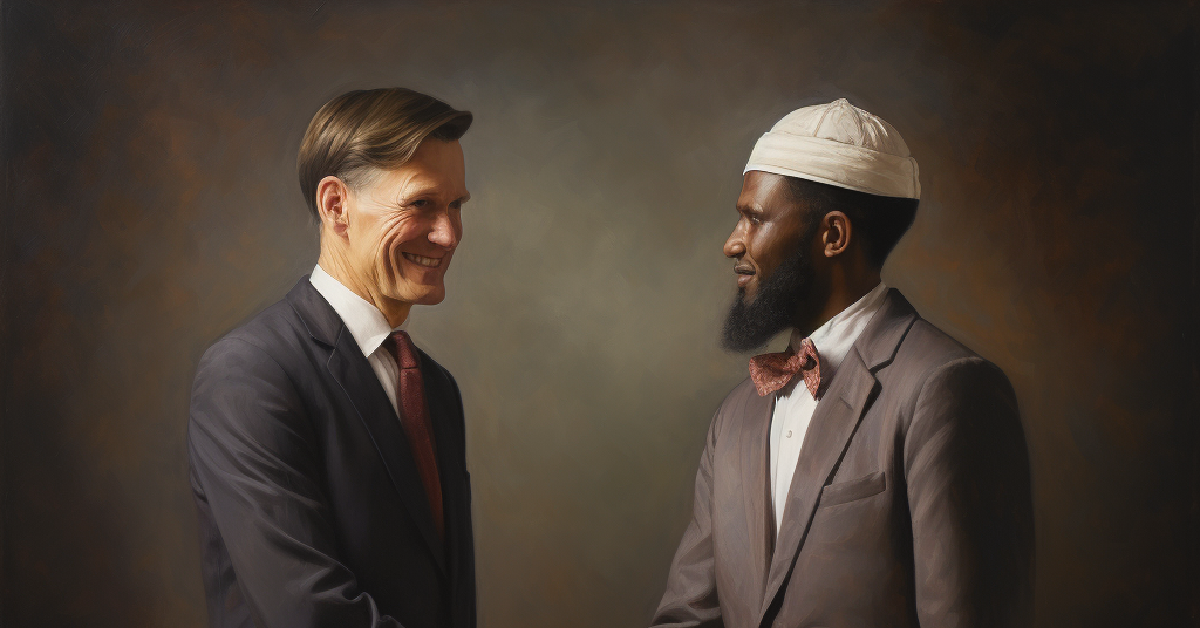

This is a mysterious paradox of Biblical faith: God is pursuing man … His will is involved in our yearnings. All of human history as described in the Bible may be summarized in one phrase: God is in search of man.

In short, the Abrahamic covenant and the story of Israel is about God graciously seeking out a relationship with us. He is trying to mend the relationship that we broke off—or stepped away from. With that in mind, let’s dive into the story of the Abrahamic covenant. As Inigo Montoya said in The Princess Bride, “Let me explain. No. There is too much. Let me sum up.”

Genesis 1-11 acts as a kind of prologue to the story of Israel. It sets the scene for the role Israel will play in the salvation of the world. Beginning with the exile from Eden, these chapters lay out how mankind repeatedly gives in to wickedness (with notable exceptions, of course). This not only violates their relationships with each other but their relationship with God. But despite God’s grief and anger over the violence and corruption of mankind, He doesn’t give up on His creation. After yet another example of human arrogance and corruption (leading to the confounding of languages and scattering of peoples at Babel), a remnant of this scattered, fallen humanity is selected once again in the man Abram. With the flood option officially off the table, God wisely starts small with a patriarch and his family. Notwithstanding these small beginnings, God covenants with Abram that his descendants will become “a great nation” and as numerous as the stars. God, therefore, changes Abram’s name to Abraham (meaning “father of a multitude”). A land of promise is set aside for him, and God even promises that “kings will descend from [Abraham].”

As various biblical scholars have noted, the promises to Abraham in some sense reverse the curses laid out at the Fall of Adam and Eve. They are, in some sense, a restoration of the original promises and intents expressed in Eden: a land of abundance, lots of descendants, and royal dominion. It is through Abraham’s lineage that God will gather scattered, fallen humanity to Himself. As the Lord told him, “In thee shall all families of the earth be blessed.” We also learn that Abraham’s seed will be “a light to the Gentiles,” “bearing the ministry and Priesthood unto all nations.” They will be “a kingdom of priests,” representing God before all nations and reconciling all nations to God. They will be expected to “be holy” as God is holy, purifying the land and its temple for God’s presence to be restored to the earth once more. Abraham’s family thus becomes the vehicle of the covenant and the channel through which God’s universal blessings will flow. Through Abraham’s posterity—the nation of Israel—humanity will be reconciled to God and brought back into His presence.

But from Abraham onward, Israel fails to live up to its covenant and mission: from the Exodus to the establishment of the monarchy to the division of the kingdom. They are eventually scattered into exile, first by the Assyrians in the north (often called the Lost Ten Tribes) and then by the Babylonians in the south. Various prophets in the Old Testament declare that through this scattering, God will whittle Israel down to a faithful remnant—a group whose restoration would signal to the world the benevolence and faithfulness of Israel’s God. The Book of Mormon itself is part of this remnant theology. According to its title page, it was written by and to “a remnant of the house of Israel” for the purpose of showing them “the covenants of the Lord” and “that they are not cast off forever—And also the convincing of the Jew and Gentile that Jesus is the Christ, the Eternal God, manifesting himself unto all nations.” In short, the story of Israel in the Old Testament is a story of scatterings, remnants, and covenants.

Now we often go to the scriptures in hopes of finding models of moral behavior. However, the authors of the Old Testament seem far less concerned about that. This is why we tend to get very raw depictions of prophets and the people of God throughout the Old Testament: the good, the bad, and the ugly. But I would suggest that this is, in fact, the point. The overarching theme throughout the scriptures—both ancient and modern—is God’s faithfulness to us, despite our infidelity towards Him. The story of the Abrahamic covenant is about God keeping His end of the covenant while providing space and numerous opportunities for us to keep our own. His hand of fellowship is continually extended, even though we tend to slap it away over and over again. And yet, despite these constant rejections, He still seeks us out. But God’s search for man doesn’t end with Him merely waiting for us to repent. As Abinadi prophesied in the Book of Mormon, “God Himself shall come down among the children of men, and shall redeem his people.” Jehovah made the covenant with Abraham but then stepped in Himself to guarantee its fulfillment.

Jesus as Israel’s God, Priest, and King was Israel’s ultimate representative: what Israel was meant to be all along. And as Israel’s representative, He could bear the sins of the nation. But since Israel’s mission was to be a “light to the Gentiles” and the means through which all nations would be blessed and redeemed, its representative consequently bears the sins of the entire world. Through His atonement and resurrection, Jesus—“the son of David, the son of Abraham” as Matthew puts it—blesses all nations. Christ’s atonement is what makes a covenantal relationship with God not only effective but possible. God’s covenanting with us, therefore, is an act of grace: a gift that God was in no way obligated to give. King Benjamin makes it crystal clear that we are “eternally indebted” to God. Even if we were keeping all the commandments (which we’re not), we would still be “unprofitable servants.” Covenant-keeping is not earning salvation.

So if covenants are not means of earning salvation, what exactly are they? Biblical scholars have noted that covenant language is loaded with kinship language. In other words, by making a covenant, one becomes family and takes on all the obligations of a family member. This is why the nation of Israel is sometimes called God’s “son” or depicted as God’s wife in the Old Testament. Even the term “Redeemer” or “redemption” refers to the legal obligations of near kin.

So if a covenant is a family relationship, this means that the ordinances and commandments associated with covenant-keeping are also relational in nature. They are pro-social. They show us how to properly relate to God and to one another. They teach us how to be what God is; how to be “partakers of the divine nature.” They train us to desire the eternal over the temporal. President Dallin Oaks sums it up this way:

Final Judgment is not just an evaluation of a sum total of good and evil acts—what we have done. It is an acknowledgment of the final effect of our acts and thoughts—what we have become. … The commandments, ordinances, and covenants of the gospel are not a list of deposits required to be made in some heavenly account. The gospel of Jesus Christ is a plan that shows us how to become what our Heavenly Father desires us to become.

It is through these mediums of commandments, ordinances, and covenants that God nurtures His relationship with us and our relationships with each other. Loving parents not only provide for their children but help with their children’s maturation and development. Similarly, covenants with God are meant to be transformative. Brad Wilcox nailed it when he said, “We are not earning heaven [when we keep our covenants]. We are learning heaven.”

The universal reach of the Abrahamic covenant, its gifted nature, and its efficacy through the sacrifice of Christ should demonstrate to us that “the worth of souls [including each one of us] is great in the sight of God.” There isn’t a single person that Christ did not die for. There isn’t a single person who cannot return to the covenant path. And there isn’t a single person that cannot partake of the love of God right now. As Elder Christofferson says, “we do not need to achieve some minimum level of capacity or goodness before God will help—divine aid can be ours every hour of every day, no matter where we are in the path of obedience.” Recognizing where we fall short is part of the process. The Lord said to Moroni, “… if men come unto me I will show unto them their weakness … my grace is sufficient for all men that humble themselves before me, and have faith in me, then will I make weak things become strong unto them.” There isn’t a single person that Christ did not die for….And there isn’t a single person that cannot partake of the love of God right now.

Returning to the story of the fish and water, David Foster Wallace ends his commencement speech by encouraging “awareness of what is so real and essential, so hidden in plain sight all around us, all the time, that we have to keep reminding ourselves over and over: ‘this is water, this is water.’” Similarly, I would encourage us all as we dutifully attend our church meetings, as our minds wander off while partaking of the sacrament, as we’re stretched thin by our callings, as we try to not be rote in our prayers, as we try to stay awake while reading our scriptures, as we struggle to be more charitable, as we desperately seek revelation, as we really try not to lose it with our kids or our spouse, as we attempt to forgive, as we work hard to overcome an addiction, as we slowly-with-guaranteed-detours-on-the-way become disciples of Christ, as we do all of these things and more, that we look at these commandments, ordinances, and covenants and remind ourselves over and over:

This is grace. This is grace.