Bishop Gérald Caussé, the leader of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ temporal affairs, recently discussed environmental matters: “Our Earthly Stewardship.” During my first hearing, watching with a toddler, I thought I heard standard environmental platitudes. But in a later reading, I saw something more subtle: the seed of a whole gospel vision of environmental issues.

Rather than advocating a specific political stance, he provides clarifying principles, helping us understand the Creator’s purposes for the environment. Bishop Caussé focuses our attention on our fellow men:

Our stewardship over God’s creations also includes, at its pinnacle, a sacred duty to love, respect, and care for all human beings with whom we share the earth. They are sons and daughters of God, our sisters and our brothers, and their eternal happiness is the very purpose of the work of creation.

In this vision, our role as stewards of the Earth is intrinsically tied to our relationship with our fellow human beings, whom we are to love, respect, and care for as children of God.

The Limitations of Nature

Obviously, the sort of environmentalism that bemoans the existence of so many humans does not mesh well with the view that the purpose of the earth is to have many happy humans on it. Saints should not regret humanity’s existence. The Family Proclamation states, “We declare that God’s commandment for His children to multiply and replenish the earth remains in force.” When human life hangs in the balance against other possible priorities, as it inevitably does in a world of economic scarcity, it should weigh heavily. A faith with apotheosis at its core can hardly avoid anthropocentrism. This has consequences for our relationship with the natural world. The purpose of the earth is to have many happy humans on it.

The title “Our Earthly Stewardship,” as used by Bishop Caussé, itself implies that we are caretakers of the earth with a specific purpose. A steward should not, like the unwise servant given one talent, fearfully keep his stewardship in some pre-existing state.

Similarly, while there is a place for conservation, we shouldn’t idolize naturalness for its own sake. Caussé illustrates this as he discusses visiting Monet’s garden. Monet “immersed himself in nature’s splendor” not by letting natural processes operate free from the unhallowed influence of man but by working for 40 years as he “tenderly shaped and cultivated his garden.”

A saint might reasonably wonder whether environmental changes on a larger level are desirable. If the pre-industrial (“natural”) level of CO2 or stratospheric aerosols can’t be presumed optimal just because it is natural, what is the optimal level? And what action might be desirable to get there? These questions should be approached with due caution and epistemic humility, using scientific tools, but can only be framed correctly if the proper goal is held in mind: serving the planet’s divinely ordained purposes. (These would likely not be well served by either runaway warming or by a “natural” reversion to an ice age, and staying on the road between those ditches is not necessarily identical to maintaining the atmosphere in a “natural” state.)

For the planet is not an end in itself. Humanity seems to suffer a recurring temptation to see transcendent beauty in nature and stop there without seeing through to nature’s Creator. This has resulted in both ancient and modern polytheism: ancient worship of the sun and earth as gods and modern worship of the natural world as being, in practice, the highest good we have access to (gods being out of fashion). Today’s self-flagellating environmentalism resembles yesterday’s sacrifice to the sun god.

The first of the Ten Commandments remains relevant: “Thou shalt have no other gods before Me.” All of this challenges an anti-human perspective or a naive enthusiasm for the natural above the human.

Using the Earth to Excess

However, God comments in Genesis that most elements of His creation are “good,” and elsewhere, we are cautioned about our relationship with that creation. For example, the President of the Church of Jesus Christ, Russel M. Nelson, counsels that “We should … preserve [the earth] for future generations.” And Latter-day Saint scripture teaches that the earth should be used “with judgment, not to excess, neither by extortion.”

This cautions against one or both of two things: 1) Using the earth to excess for the earth, or 2) Using the earth to excess for yourself.

Elsewhere, scripture says, “the earth is full, and there is enough and to spare,” so using the earth to excess for the earth does not appear to be the key concern. It is easy (too easy) to decry others for using the earth “to excess.” It is less comfortable to consider where one’s own use of resources might go “to excess,” but here, scripture has plenty to say.

Shortly after telling us “the earth is full, and there is enough and to spare,” the Doctrine and Covenants continues to caution that “if any man shall take of the abundance which I have made, and impart not his portion, according to the law of my gospel, unto the poor and the needy, he shall, with the wicked, lift up his eyes in hell, being in torment.” Elsewhere, the revelations tell us that “if ye are not equal in earthly things ye cannot be equal in obtaining heavenly things.”

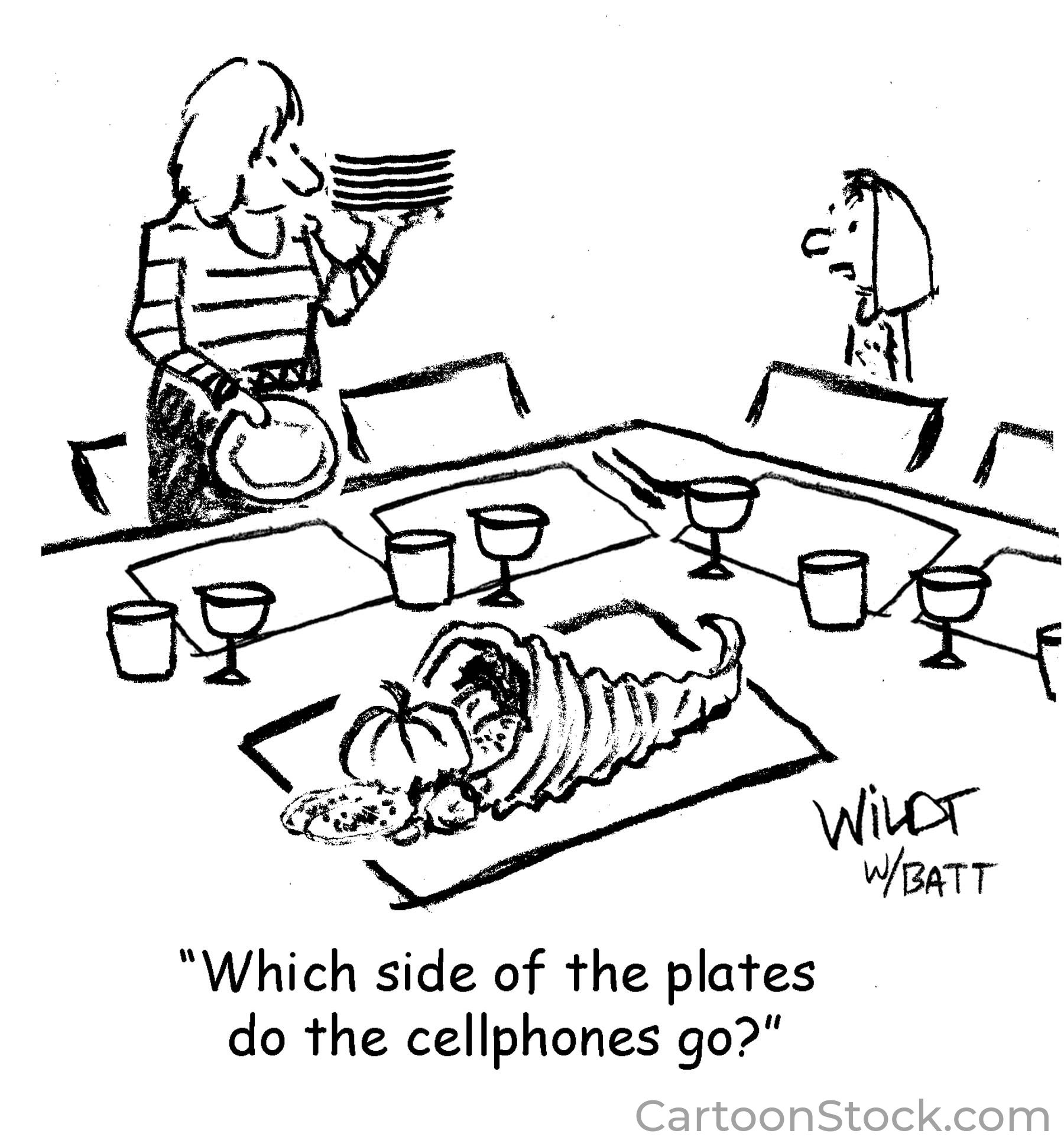

The underlying eternal principle is that we should freely choose some approximation of consumption equality. If you look up and down the pews at Church and have a sense that you are consuming vastly more economic or material resources than the people next to you, something is wrong. Don’t buy that second private jet; “impart your portion” to “the poor and the needy.” From one perspective, your dollars could go to something other than a jet. But from another perspective, the resources from the earth embodied in the jet could have gone elsewhere—perhaps to build a turbine generator in a developing country. The jet “take[s] of the abundance which [the Lord] has made” by using metals, oil, etc., far beyond your actual needs, pushing costs up for marginal consumers and functionally pricing them out of the earth’s resources. Avoid excessive or sinful consumption.

Caring for the Earth by Caring for Others

Scripture also warns us not to use the earth’s bounty “by extortion.” At first glance, this seems to indicate that we should not extort resources from the earth using illegal or unethical methods. Illegal logging and artisanal mining using child labor are candidates for condemnation under this reading. However, extortion is usually a crime against a person. This phrase could also be read to command against extorting the earth’s resources from each other by sinful means.

So we should avoid excessive or sinful consumption and care for the “good” earth. And simultaneously, we must not make nature an idol nor forget the human purposes of its creation. Proper environmentalism should not demonize the existence of God’s children; it should find ways to serve them—especially the poor and hungry.

None of this directly answers public policy questions. These include everything from the management of national parks to efforts to respond to climate change to the regulation of industrial wastewater quality. Positions on these questions can’t be deduced directly from the gospel; they must also rely on our imperfect understanding of imperfect empirical data. Reasonable saints disagree on many such matters and may change their own positions as more information becomes available. Such disagreements may map into partisan politics in a variety of ways.

However, gospel principles do provide a framework for approaching such policy questions. Even more importantly, they provide a framework for individual life within our natural environment. May eternal truth inform our choices as we steward God’s creation to further His goals.