In a world that moves at breakneck speed, finding moments of stillness and escape can be challenging. The demands of work, family, and social media can leave little room for contemplation and reflection. But research shows that reflection and escape are crucial for our physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual health.

Religion provides unique opportunities for reflection and escape through practices like prayer, scripture study, and worship services—and even extended escape such as the upcoming General Conference.

In a world that often worships busyness and multitasking, if we don’t carve out time for developing our spiritual core, we will soon find it waning. By embracing religious practices, we can find moments of stillness and connection that can enhance our overall well-being and quality of life.

The Benefits of Reflection and Escape

Reflection is the process of examining our thoughts, feelings, actions, and experiences to gain insight, learning, and meaning. Escape is the act of withdrawing from the stressors and pressures of everyday life to find peace, relaxation, and joy. Both reflection and escape have many benefits for our physical, mental, emotional, and social health.

According to research, reflection gives the brain an opportunity to pause amidst the chaos, untangle and sort through observations and experiences, consider multiple possible interpretations, and create meaning. This meaning becomes learning, which can then inform future mindsets and actions. Reflection can also help us improve our self-awareness, which can lead to better decision-making and performance, increased empathy, reduced stress, enhanced creativity, and greater happiness.

Escape can also have positive effects on our well-being. According to studies, spending time alone or in silence can help us promote self-awareness, reduce stress, improve memory, boost immunity, lower blood pressure, increase happiness, and foster creativity. Escape can also help us reconnect with ourselves, our values, our passions, and our purpose.

The Challenges of Finding Time for Reflection and Escape

Despite the benefits of reflection and escape, many people struggle to find time for them in their lives. Some of the challenges they face include:

- Busy schedules: Many people have hectic lifestyles that leave them little room for leisure, hobbies, or rest.

- Constant distractions: Many people are constantly exposed to noise, media, notifications, and other stimuli that compete for their attention and prevent them from focusing on their inner thoughts or feelings.

- Pressure to be productive: Many people feel guilty or anxious about taking time off or doing nothing. They may believe that they have to be always working or achieving something. They may also face expectations from others (such as family, friends, employers, or themselves (such as goals) that make them feel obligated or compelled to keep busy.

These challenges are partly influenced by cultural trends that devalue or discourage reflection and escape, such as:

- The cult of busyness: This is the idea that being busy is a sign of success, intelligence, or importance. It creates a sense of urgency or competition that makes people feel like they have to do more or do it faster.

- The myth of multitasking: This is the belief that doing multiple things at once is more efficient, effective, or desirable. It leads people to divide their attention or switch between tasks without fully engaging with any of them.

- The fear of missing out: This is the anxiety that one might miss something important, interesting, or fun. It drives people to constantly check their devices, social media accounts, or news sources, even when they are supposed to be relaxing or reflecting.

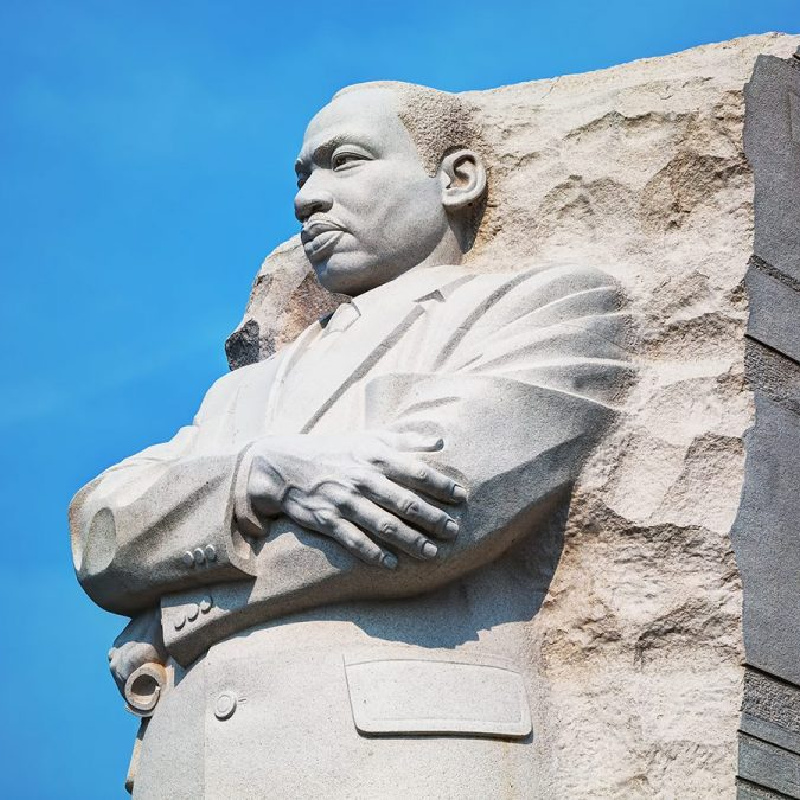

The Role of Religion in Providing Opportunities for Reflection and Escape

One way that people can overcome these challenges and find time for reflection and escape is through religion. Religion can provide opportunities for reflection and escape through various practices, such as:

- Prayer: Prayer is a form of communication with God or a higher power that allows people to express their gratitude, requests, confessions, praises, or questions. It can help people reflect on their lives, their relationship with God, their values, and their goals. It can also help them escape their worries, fears, or troubles and find peace, comfort, or guidance.

- Scripture study: Scripture study is the practice of reading and studying sacred texts that contain the teachings and revelations of God or a higher power. It can help people reflect on their faith, their understanding of God, their morals, and their actions. It can also help them escape from the distractions and temptations of the world and find wisdom, inspiration, or direction.

- Worship services: Worship services are gatherings of believers who come together to worship God or a higher power through various forms such as singing, listening to sermons, participating in rituals, or sharing testimonies. They can help people reflect on their community, their role in God’s plan, their gratitude, and their commitment. They can also help them escape their isolation, loneliness, or stress and find joy, fellowship, or support.

The Unique Benefits of Religious Reflection and Escape

Religious reflection and escape differ from secular practices such as mindfulness or meditation in several ways. One of the main differences is that religious reflection and escape involve a connection with God or a higher power, who is seen as a source of love, grace, mercy, and truth. This connection can provide spiritual benefits that go beyond the physical or mental benefits of secular practices.

It may seem obvious, but taking time to be religious increases our faith. Religious reflection and escape can strengthen one’s faith in God or a higher power by increasing one’s awareness of His presence, His power, His goodness, His will, His promises, His guidance, His forgiveness, and His love Faith can help one overcome doubts, fears, trials, temptations, or challenges. Faith is more than commitment to your religious idealogy; it’s an attribute that contributes to strong mental health.

Taking opportunities to reflect on the spiritual can give you an increased understanding of God which helps people be more confident. Religious reflection and escape can deepen one’s understanding of God or a higher power by increasing one’s knowledge of His attributes, His works, His ways, His purposes, His commands, His expectations, His gifts, and His plans. Understanding can help one appreciate God more, trust Him more, obey Him more, serve Him more, praise Him more, and glorify Him more.

Religious reflection and escape can reveal one’s purpose and meaning in life by increasing one’s alignment with God’s plan for oneself, for others, for the world, and for eternity. Purpose and meaning can help one find fulfillment, happiness, hope, motivation, direction, and resilience.

And lastly, when we take time to be religious not in a silo, but as part of a broader religious community, it can affirm one’s belonging and identity as a child of God or a follower of a higher power by increasing one’s recognition of His love, His grace, His mercy, His acceptance, His adoption, His calling, and His inheritance. This is true even when we are partaking in the same event virtually, such as general conference. Belonging and identity can help one feel valued, loved, secure, confident, worthy, and unique.

Religious reflection and escape are practices that can enhance one’s mental health by providing physical, mental, and spiritual benefits. They can help people reflect on various aspects of their lives and faith and escape from various sources of stress and negativity. They can also help people connect with God or a higher power, who can provide them with faith, understanding, purpose, meaning, belonging, and identity. A religious escape can ultimately improve our happiness, well-being, and quality of life.