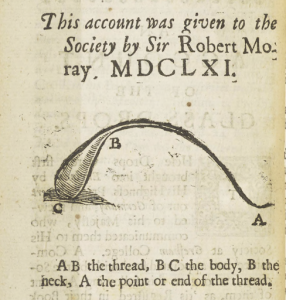

Prince Rupert’s Drops have fascinated scientists from the 17th century to the current day. They are tadpole-shaped pieces of glass with long, sinuous tails. To create one, a glassmaker drops molten glass into water. This causes the outer layer of the glass droplet to cool very rapidly. The inner core cools much more slowly. As it does, it seeks to contract, but it can’t. That’s because the outer layers have already contracted. This creates “residual stress.” Long after the cooling is complete, the outer layer remains locked in extreme tension, pulled towards the inner core.

The result of this extreme tension is that the outer layer—the bulbous part around the inner core—attains remarkable strength. How much? Enough to easily withstand a hammer blow or to even shatter a bullet. Prince Rupert’s Drops do have an Achilles’ heel, though: if the long tail is snipped, the entire drop will explode into powdered glass fragments as the tension is finally unleashed. But as long as the tail remains intact—as long as the strain remains in place—they are unbelievably strong. From our limited human perspectives, it is actually very common for honesty and kindness (just to give one example of tension) to come into conflict.

Another example of the structural benefits of constant strain comes from radio masts. These narrow towers are some of the tallest structures humanity has ever built. One example is the Warsaw Radio Mast, which was the world’s tallest structure until it collapsed in 1991 (more on that later). The Warsaw Radio Mast reached almost half a mile into the sky (more than 2,120 feet), but it was only as wide as an SUV (16 feet on each of its three sides). How is it possible to keep such a thin tower standing?

The answer, as with tempered glass or Prince Rupert’s Drops, is tension. In the case of masts—including radio masts but also masts on sailing ships—the tension is provided by ropes or cables called guy wires or “stays.” These stays are not only anchored to the ground (or the ship) to keep the mast from leaning in any direction, they are kept “taught” or tightened. Ironically, pulling the mast down provides the tension that gives it enough strength to stand tall.

Critically, these stays have to be in place on all sides of the mast. If only one side is anchored, then, of course, the mast will tilt to that side. So, in another paradox, the way to prevent the mast from tilting to the left or to the right is to pull it to both the left and the right.

The Warsaw Radio Mast collapsed in August 1991 when one of the main stays was disconnected so that it could be replaced. Two temporary stays were supposed to take its place, but a gust of wind caught the mast before they were properly anchored. The mast twisted, ripping other stays free of their anchors, and then snapped about halfway up. The mast collapsed from a lack of paradoxical tensions. Without the strain supplied by the stays, the mast lacked the continuing strength to stay upright.

The reason I got to thinking about Prince Rupert’s Drops and radio masts and stays has to do with a tragic tendency I have seen unfold far too often in contentious online discourse. How often have you heard honesty cited as a reason to abandon kindness and embrace hard-edged contention? Or, conversely, fear of contention used as a pretext to silence dissent or suppress sincere concerns?

You could argue that properly understood, all virtues exist with each other in harmony. That is probably true. I, too, believe that ultimately all virtues can be reconciled with each other from God’s perspective. In the final analysis, honesty and kindness will never conflict. But we don’t have God’s perspective, and the analysis we conduct is very far from final. From our limited human perspectives, it is actually very common for honesty and kindness (just to give one example of tension) to come into conflict. What should we do when this happens? And when we find ourselves torn not between obvious good and obvious evil but trying to muddle our way through conflicting, irreconcilable (to us, for now) virtues?

First, we should not let go of any one virtue. The tension of striving to hold onto kindness and honesty both—together—is like the tension that keeps a radio mast from collapsing or that gives tempered glass its strength.

Holding on is not easy to do. Tension is uncomfortable, and the arguments in favor of letting go can be seductively persuasive. It’s not hard to cast honesty in a courageous light and to disparage kindness as superficial niceness. Or, conversely, to celebrate the ideal of kindness while denigrating truth-telling as uncompassionate callousness. Of course, these rationalizations are compelling. That’s why we call it rationalizing—because you’re generating lots of reasons for the dubious conclusion you prefer.

But that easiness is a trap. It’s like snipping the tail of a Prince Rupert’s Drop. Once the tension is gone, there is no strength left. Any virtue, divorced from the society of other virtues, becomes a monstrous idol.

As Elder Neal A. Maxwell once taught, in the “spiritual ecology” of the gospel of Jesus Christ, individual teachings “are so powerful that any one of these doctrines, having been broken away from the rest, goes wild and mad. … The principle of love without the principles of justice and discipline goes wild. Any doctrine, unless it is woven into the fabric of orthodoxy, goes wild. The doctrines of the kingdom need each other just as the people of the kingdom need each other.”

Therapist Ty Mansfield applied this last fall to the widening sexuality conflict in America—elaborating on prophetic encouragement towards embracing both “love and law” while raising concern that “most people don’t actually seem to do very well at holding this tension.” As he put it, “There are too many who seem to be more concerned with truth than love, while others are more concerned with love than truth.”

Mansfield went on to illustrate, “the morality of promoting the Church’s position on marriage and chastity is challenged to the degree that we are not at the same time looking deeply enough into the lives of others who feel somehow hurt or confused,” while also suggesting that “those who advocate for a stronger love and ministry often seem to have a kind of disregard for truth and law.” He then concluded, “I believe as we let ourselves take seriously the prophetic invitation and truly sit in this tension between truth and love, practicing more intentionally to hold both together, we can become better disciples of our Lord.”

As you can see, if you worship kindness at the expense of truth, you will be left with neither. How is it possible to be genuinely kind—genuinely concerned with the welfare of another—if you have given up regard for truthfully answering the questions of what will help or hurt them? If all you care about is honesty, then it, too, evaporates. Honesty is a condition of relationship, but how can you be honest if you no longer see other people as truly independent, valuable beings?

The easiness is a trap in another way as well. Why have we been sent here to Earth? It’s not to merely arrive at the correct conclusion to various moral questions. Propositional knowledge cannot save anyone. The devils know and tremble. That means life is not a theology exam. The reason we face these difficult, ambiguous moral choices is that the process of feeling our way through them—of holding onto contradictory virtues and never letting go, no matter the strain—changes who we are. …As we take seriously the prophetic invitation to sit in this tension between truth and love, we can become better disciples of our Lord.” Is that still too long?

Holding onto opposing virtues is not very glamorous. From the outside, it can be impossible to tell the difference between a person who doesn’t care about virtue and a person who cares passionately about two competing virtues. This is more of an inner struggle, so don’t expect accolades or even notice.

And yet it is only if enough of us persist in this inner struggle that we can resist the forces tearing the fabric of our society apart. If you cling to competing virtues and embrace the ambiguity and complexity that so often accompanies the process of arriving at moral choices, then it is easy to see people who come to different conclusions as being good and reasonable (even while you disagree). After all, the questions are genuinely difficult.

And so, in the end, we cannot choose to experience tension or not. We can only choose what kind. On the one hand, we can embrace internal tension by holding onto competing virtues. Internalizing this kind of tension between competing ideals allows a deeper connection to emerge even in the context of disagreement. This allows friendship between opponents and replaces contention with good faith contestation.

On the other hand, we can find inner tranquility by letting go of virtues one by one until we have a single, monstrous, mutated virtue left as our idol. This will result in some kind of peace on the inside. No one is calmer than an extremist who has extinguished the last embers of self-doubt and conscience. But the more of us who choose this internally “easy” path, the less peace will exist between people. Neighbor will contend with neighbor, parents and children will disown each other, and the love of many shall wax cold.

The right choice is clear, but it is also difficult. I pray we have the courage to make it anyway.