Long before animosities overtook American discourse and Black Friday invaded the entire month of November—there was something else around Thanksgiving that challenged journalists: coming up with that article aiming to help people get along with family members who drove them nuts when gathering for the holidays.

That was tricky to write before COVID-19, Black Lives Matter, and Trump v. Biden—let alone in the middle of socio-political divisions that never seem to stop escalating, and a pandemic we just can’t seem to shake. And you seriously think you’re going to be able to gather happily with family members who might not agree on all of this?

Of course, you can! And just like you needed, we’ve prepared below five simple tips to navigating these tricky gatherings like a champ!

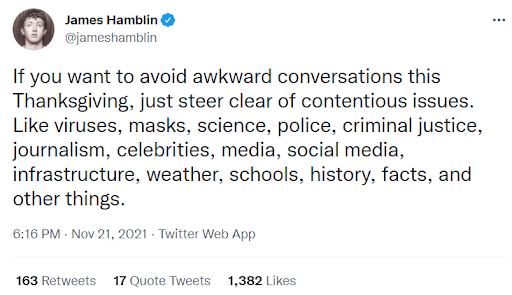

Before you dive into our serious suggestions, maybe just let yourself pause to laugh a little at how ridiculously challenging this is becoming for all of us – as James Hamblin, former writer at the Atlantic, illustrates well:

1. Respect your family and friends’ right to disagree on these matters, even if you’re not happy with their conclusions. The disagreements at hand are clearly serious. And challenging, with lives at stake in many areas (climate change, police violence, sexuality, mental health, infectious disease). But they become so much more challenging when we lose all respect for the people themselves who have a differing view of the world than we do.

You’ve probably heard the harsh words or seen the eye-rolls among some towards those who choose to follow public health guidance. And in the other direction, you’ve surely noticed mounting hostility towards those feeling resistant about the same. Whatever your own views are, the fact is that the more you believe that someone who disagrees with you on an important matter is inherently or inescapably selfish, hateful, evil, or willfully ignorant and reckless, the more painful your experience talking (and living) with them will be.

It can be helpful to remember that different perspectives on health and healing have been held by reasonable people throughout the history of the human family – much like differences over love, faith and God. Acknowledging and making space for these different views of healing (even and especially if we find ourselves strongly committed to one view), might help us see more and learn more together—while also reducing the pain of bitter judgment we may otherwise feel towards each other.

It might also be helpful to let your family members who don’t share your views know that you will respect their decision if they feel more comfortable not gathering with you—especially if you sense they may feel fearful about the possibility of being close to you, but feel unspoken pressure to do so.

Don’t forget, you can respect someone’s faith and thoughtfulness—even if you don’t respect the final conclusion they make about something. Even good people make big mistakes sometimes, right?

2. Be sensitive to honest fears among loved ones—even if you disagree with their origin. Even if you are saddened or disappointed by the conclusion someone else has reached about difficult questions, it’s possible to still appreciate the reality of fear they feel (yes, even if you don’t believe these fears have a legitimate basis). For instance, the unvaccinated might understand how difficult and scary it could be to see dissent from vaccination among those who see this as the only way the pandemic ends. And in the other direction, the vaccinated can try and understand how difficult and scary it can be to experience limitations on freedom and mounting social scorn for opting out of the vaccine campaign.

You can replicate this thought experiment for whatever political disagreement your family finds itself embroiled in. We have found ourselves growing closer to friends alarmed about climate change, by saying (irrespective of our views on climate) “if I love this person, then I should care about what they are worried about.” You can respect someone’s faith and thoughtfulness—even if you don’t respect the final conclusion they make about something.

This is the opposite of sensitivity—and you’re missing something important if this is what you’re putting out into the world. Of course, if that’s how you want to feel towards your family members this holiday season (and anyone else who disagrees with you), go for it. We’re suggesting another way—a way to show empathy and compassion to someone’s pain, even if you vigorously disagree with their reasoning and worldview.

Christians are supposed to be good at this, after all: Ministering to the downtrodden and even the sinners, even and especially when those afflicted are enduring self-inflicted wounds. As King Benjamin notes, “Perhaps thou shalt say: The man has brought upon himself his misery; therefore I will stay my hand”—going on to caution against such harshness of judgment.

This is not easy for any of us. And we can all do better at this!

3. Keep an eye on the harshness of your own judgments. In the absence of a way to foster deeper understanding, it’s common for any of us to come away with hardened, severe judgments. On one side, for instance, people can see “global warming deniers” or “vaccine skeptics” as “really just acting selfishly, thinking only of themselves—and disregarding the public good in a reckless way—while ignoring clear and obvious science to boot.”

Want to drive yourself crazy? Just believe that fully—taking it for granted as the truth about anyone who has adopted a different view than you.

In the other direction: “These global warming pushers” or “those promoting vaccination” can be portrayed as “willing conformists in a large-scale UN/Bill Gates plot to depopulate the world—and disregarding the clear signs of malicious plans to take down America’s freedom as well.”

Want to feel absolute despair about the world? Then believe that as an apt description—yes, about anyone who believes differently than you.

That doesn’t mean there is no truth to any of these perceptions, of course. Selfish and ignorant people really exist, and so do ominous “secret combinations” in the last days, at least if Book of Mormon warnings are to be taken seriously. But notice how both of the sweeping judgments mentioned above go well beyond these realities to state instead that all unvaccinated people are consciously [this despicable thing]—and that all vaccinated people are willingly [that terrible thing].

These are extreme exaggerations at best—and a profound deformation of the deeper reality, at worst—namely, that thoughtful, good-hearted people reach the best conclusions they can, based on the information they have available.

4. Do your best to not automatically dismiss others’ views. Because of these strong feelings, it’s common for any of us to quickly dismiss those who see otherwise. Those with concerns about police violence, for instance, can be written off by those who see any such complaint as a liberal assault on law enforcement. The same thing happens in the other direction, with stories of dangerous rioters dismissed as Fox News propaganda. Similar stories exist of fears being quickly dismissed about deaths happening among the unvaccinated or soon after vaccination.

In place of such sharp edges in our conversations together, how about making space for perspectives and concerns on both sides—allowing them each to be seriously considered? In a moment of such real and imagined dire threats socially, economically and in terms of the pandemic, wouldn’t the larger truth require that larger space of us? Do your best to try and stay in a place where you can allow yourself to at least make space for others’ views, without knee-jerk rejection to preserve your sense of order.

As part of this, avoid rhetorical power-plays in gatherings of family or friends that dismiss all nuance and dissent—such as implying that all the science is on your side. Notice how both sides are doing this now (on virtually all issues—e.g., “#science!”) However convicted you are about your view of the data—and however strongly public opinion or expert consensus may be aligned with you—it will always be true that thoughtful voices and experts hold different views on this all. Admitting that might help all of us breathe a little more.

Some may worry that cultivating such space provides cover for people to “feel safe” while adopting dangerous beliefs—living out ideas that are hurting many people. From that perspective, it’s better to leave people uncomfortable and not seek to cultivate warm and welcoming space. While acknowledging this view, we simply point out three facts: (1) people on both sides of the present pandemic conflict now believe the ideas on the other side are doing great harm (2) This is not necessarily unique and arguably true of virtually all issues—from sexuality and climate change (“your ideas are hurting gay kids or leading the planet to destruction”) to faith convictions (“your ideas are leading people away from eternal happiness”). (3) Intentionally adopting an attitude that “the best course of action is to make you perpetually uncomfortable in my presence as long as you hold X view” is a sure-fire way to make any of these conversations way harder. And where does that leave us?

5. Be compassionate to those facing particular pressures. Although there is palpable fear on all sides of these conversations, the level of pressure and scorn is not equivalent. For example, conservatives with questions about new policies tied to climate change or transgender rights are increasingly under enormous cultural pressure to align with popular opinion. And when it comes to the pandemic, although fears clearly exist on all sides, many of the unvaccinated are losing jobs and having freedoms restricted severely. Job loss is a difficult trial anytime, but especially in the holiday season.

Along the socio-political spectrum, conservative positions on virtually everything are increasingly scrutinized. And those who question medical orthodoxy are likewise subject to heightened critique. Indeed, public narratives are also framing the unvaccinated as solely responsible for the perpetuation of the pandemic. Speaking of the resurging case numbers, White House press secretary Jen Psaki, for instance, said “the reason we’re here is because people have not gotten vaccinated—not because of any other reason.” In place of such sharp edges in our conversations together, how about making space for perspectives and concerns on both sides.

This is a great model. Jeff Lindsay’s Meridian piece, “Let’s Have Some Compassion for Our Untouchables” is another good illustration of an attempt at greater compassion.

Don’t forget: The alternative hurts even more. None of this is easy: Sitting with discomfort, hearing the fears of someone you disagree with, showing empathy to someone whose views drive you nuts, etc. But recognize how much more it hurts not to do this. Why? Because people who don’t actually seek understanding end up stewing in their resentments—in a kind of toxic brew that stays with them over time. And chronic anger—much like its sister of chronic stress—hurts. It even leaves residual consequences in the body, just like stress.

This is no theoretical proposition. Think of the last time you were carrying around a grudge or frustrations towards someone—with irritated thoughts and agitated feelings preoccupying you in the middle of other activities, and even following you to bed.

How did that leave you feeling? As you can see from your own experience, staying frustrated with someone (or lots of someone’s) over a long period of time Just Plain Hurts.

And the hurt on these questions seems to extend in all directions right now. Every other day, we hear another story of a family grappling with tension and rising feelings on this issue: siblings being condemned as ignorant or reckless for their vaccination decision, grandparents issuing ultimatums of who can come to a family gathering based on vaccination status, etc.

The good news is if we open (and soften) our hearts towards each other, we believe that we can return to a place of less angst and pain, while helping others around us find that too. One doctor who has spent time going around the country listening to the concerns of those who are vaccine-hesitant demonstrated this in her Atlantic piece earlier this fall: “If I was only going off what I saw online, I’d probably agree that everyone who wasn’t vaccinated is being selfish and difficult. But talking to people like those church groups has changed how I feel completely.”

Could this kind of listening—even flirting with some curiosity—change things completely for our families too? We hope so.

We’re focused especially on pandemic differences here. But much of this would apply equally well to differences over Black Lives Matter, immigration, Trump vs. Biden, and even about the Church of Jesus Christ itself. Check out this loving conversation model from John Kesler helping families navigate conflicts over the Church of Jesus Christ when they gather together.

Yep, all this is hard work—but, once again, the alternative is so much more draining and difficult for our relationships.

So, let’s start talking, listening—and yes, even making space for our different views.

Then, maybe we can start to suffer less, and enjoy the holidays together for real.