National Religious Freedom Day stings a little this year.

The past few months have brought some painful experiences to members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In September, a shooter and arsonist took the lives of four members of the Church and wounded several more in Michigan. Just hours before, the Church’s senior leader, President Russell M. Nelson, had passed away. In our mourning, many online expressed great sympathy and kindness. But sadly, some saw fit to focus on hurtful arguments that Latter-day Saints aren’t Christian—and in some cases, argued that we’re simply demonic.

Around the country this fall, explicit chants about “Mormons” echoed through several college football stadiums where BYU played, including at a game where survivors of the Michigan attack were in attendance. Although apologies followed, they claimed that the actions did not represent the university, and no actions were taken to help remedy the students’ animus. (I do note that some schools took intentional steps to prevent these hateful chants, which I gratefully applaud.)

We focus on living our faith.

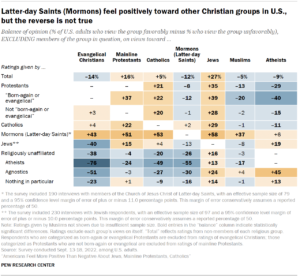

All this in a time where Pew Research Center has reported a great irony: while Latter-day Saints are unique for feeling positive—and in most cases, very positive—toward all faith groups (and even atheists), they are, in return, disliked by nearly all those groups. (A shout-out to our Catholic friends, the only surveyed group to feel positively.)

The way that Latter-day Saints face religious hostility in America is unique. Commentator Jonah Goldberg of The Dispatch said it well after the Michigan shooting: “I think extreme anti-Mormonism may be the most reactionary form of hatred in America” because it is “hating people solely for what they believe.” The hatred “is overwhelmingly theological and abstract” and does not appear to be inspired by “anything that Mormons”—or as we’d kindly suggest, Latter-day Saints—“actually, or even allegedly, do.”

This peculiar theological hate often leads to a strange cultural tolerance for degrading Latter-day Saints in the public square in ways that would not be deemed permissible for other faiths. For all the talk in recent years of shedding hate and cultivating tolerance, love, and respect, it hasn’t seemed to apply in a widespread way to members of The Church of Jesus Christ. As Simran Jeet Singh of Religion News Service reported, “Hating Mormons remains socially permissible in modern America, just as it was nearly 200 years ago when they were forcibly displaced and almost exterminated.”

Yet despite the peculiar flavor of religious animus prevalent toward Latter-day Saints in America, I don’t think most of these cultural slights weigh too heavily on Latter-day Saints. Most of us have (perhaps sadly) grown accustomed to routine maligning by the media and the entertainment industry. We know we are countercultural—or in scriptural parlance, a “peculiar people.” The scriptures teach us to expect persecution and pay no heed to the world’s judgment. We focus on living our faith and finding joy in Christ, and we don’t spend much time fretting about this mistreatment.

But the violent attack—that was different. That pain pierced our historical consciousness, searing into our remembrance the violent persecution the early Saints in Missouri faced nearly two centuries ago. A much different context, yes. But the common thread? Hate-fueled violence toward Latter-day Saints.

I have followed religious freedom conditions around the world for nearly six years. My interest in advocating for the persecuted drove me to law school and inspires me to volunteer my free time to the cause. I frequently read horrific reports of mass atrocities, including war crimes and genocide. My heart grieves every time. Sometimes I become so consumed that the suffering persecuted are all I can think about.

And yet the Michigan attack shook me differently. Perhaps because Latter-day Saint meetings and chapels are so universal, and because I have spent nearly every Sunday of my life in them, I felt that I could visualize every moment of the attack as if I had been there. I could see the lay bishopric member at the stand when the truck drove into the building, the unassuming carpet on which the members would have run as they scattered, the hallways with gospel art where each member would have frantically searched for a safe way out.

I wept for days after this attack. And I felt intense guilt that I do not weep every time I read of one. It is my firm conviction that every human life holds equal inherent worth and dignity. This belief is what drives me to advocate for the religious freedom of all people. And yet I suppose we are all most emotionally affected by what we are most intimately connected to.

But now I no longer view my emotional response to my own faith’s suffering with shame. Instead, I see it as an impetus for me to better bear the burdens and “mourn with those that mourn” outside of my faith community in the wake of religious violence. Having briefly tasted, if only from a distance, the sting of religious violence aimed at my own faith community, I can more empathetically engage with others who have endured it too.

And sadly, many have. Just a month before the Michigan attack, an attacker opened fire on Annunciation Catholic Church in Minneapolis, killing two children. In June, a heavily armed man opened fire on CrossPointe Community Church in Michigan and was fatally shot. In May, a Jewish couple who worked for the Israeli embassy was shot and killed outside the Capital Jewish Museum in Washington, D.C. Similar attacks have happened to various people of faith and houses of worship across the country in recent years.

And for minority faith groups in America, religious persecution in the form of hate crimes, even if not violent, is too often a real and pervasive part of their experience. Of the 3,096 hate crimes motivated solely by religious bias in 2024, the three most affected groups were minority faith groups: about 69 percent of the religious hate crimes were targeted at Jews, 9.3 percent were targeted at Muslims, and 4.9 percent were targeted at Sikhs.

Antisemitism in the United States is surging. In 2024, the Anti-Defamation League reported the highest total number of antisemitic incidents since it began tracking data in 1979. 77 percent of Jews have reported feeling less safe in the U.S. since Hamas’ October 7, 2023, attacks in Israel, according to a report by the American Jewish Committee. And the same report indicated that more than half of U.S. Jews avoided a behavior in 2024 due to fears of antisemitism.

Islamophobia is also increasing significantly. 70 percent of Muslims have reported facing increased discrimination in American society since the Hamas–Israel War began. The Council on American-Islamic Relations reported the highest number of anti-Muslim and anti-Arab incidents in 2024 since the group began compiling data in 1996.

These trends are not limited to the United States. Just days after the Michigan attack on The Church of Jesus Christ, a Manchester synagogue was attacked during Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Jewish calendar. The Manchester attack had startling similarities to the one in Michigan: the attacker drove a vehicle toward the sacred space (though this time, not into it), then exited in an attempt to violently attack the worshippers.

My heart grieves every time.

As Latter-day Saints engage in dialogue about religious persecution—which I fully encourage—we must make sure we understand the broader context of religious persecution and hostility in the U.S. and abroad. As we join the conversation, we must neither understate or overstate our own case. Yes, we are often treated in highly unusual ways, particularly culturally, that should be adamantly condemned. But in so many ways, we fare much better than others in our acceptance, freedom, and safety in society. We are not persecuted the way we were in the early days of the Church. We are not victims of atrocities like ethnic cleansing or genocide because of our faith ties. Many of our fellow human beings are not so lucky.

If we plan to advocate for ourselves, we should first become better aware of the other faith groups experiencing religious hostility and persecution. We should realize that we do not carry the same fear that many Sikhs or Muslims or Jews carry when they leave their homes dressed in religious apparel. We do not know what it is like to have an ethnic-religious identity, with both aspects triggering acts of discrimination against us. We should try to better understand the experiences of our brothers and sisters for whom these forms of persecution are daily realities. And we should understand hostility toward or persecution of Latter-day Saints in this broader context.

If we wish to advocate for ourselves, there is always the question of whether to turn the other cheek or to defend a righteous cause. In my own view, while we must seek to turn the other cheek and achieve personal reconciliation, and we must forgive those who have persecuted us, scripture teaches it can be righteous to advocate for ourselves as a group when we are persecuted as a faith community (so long as we did not provoke the offense). Restoration teaching adds that this advocacy should be peaceful.

In fact, I think it is important for members to peacefully and respectfully advocate for our faith community when we experience persecution: first, because it is just, and second, because it signals the standard of how we believe all human beings and their religious beliefs should be treated. If we don’t speak up about cultural desecration of the Book of Mormon in a musical, are we implying it’s okay to desecrate the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh), the Qu’ran, or the Bible? If we imply that hate speech against us is okay, do we think it’s okay against Buddhists, Sikhs, or evangelical Christians? Would we stand for explicit chants against them at sporting events or vile tweets against them on X in the wake of religious violence aimed at their communities?

Even if you don’t want to deal with the question of whether self-advocacy is righteous, one thing is surely just: advocating for the religious freedom of others. In so doing, we honor the human dignity—the inherent, unchangeable, equal worth—of every person. We recognize that to be human is to have a conscience, and that from this follows the corollary human right to follow it. We emphasize that all human beings deserve to be treated with kindness, respect, and love—no matter what aspects contribute to their identities.

When it strikes others, I will condemn it too.

It may seem paradoxical for people of faith to advocate so intently for the rights of others to believe and act in ways that they may not believe to be fully theologically or soteriologically correct. And yet, for Latter-day Saints, preserving the freedom of the human spirit to act according to conscience is an act of religious devotion itself. It is a way of honoring the Plan of the Father and the beings created in His image who possess the sacred agency with which He endowed them.

The Good Samaritan in Jesus’ parable was the unlikely advocate and rescuer for the injured Jewish man. Jews viewed Samaritans as religiously impure and heretical. Samaritans saw Jews as arrogant and wrong. And yet, the Samaritan man was the one who both noticed the wounded Jewish man and addressed his needs. Laying aside the tension between their communities and perhaps their inabilities to fully understand each other, the Samaritan had compassion for the Jewish man. However different from himself, the Samaritan saw the humanity in the other, “shewed mercy,” and helped the broken Jewish man heal from what he had so cruelly been a victim of. The Jewish man was not the Samaritan man’s enemy, but his neighbor and his brother.

This is our example. We must set aside our differences to advocate for the religious freedom of other faith groups. We may not fully understand them, and they may not understand us. Sometimes, there may even be significant theological rifts or cultural tensions between us, including harsh words uttered. But we can choose to see the humanity in one another and to stand for it.

So, on this National Religious Freedom Day, when persecution strikes my faith group, I commit to peacefully but firmly condemn it. And when it strikes others, I will condemn it too—perhaps even more vigorously.