When was the last time you made something? Besides your bed or a peanut butter jelly sandwich?

GK Chesterton begins his book The Everlasting Man with an effort to rehabilitate the so-called caveman. Archeology has shown that, far from being unsophisticated, grunting-and-scratching dullards, early humans who dwelled in caves were artists who showed impeccable taste and discernment. Their drawings of horses and reindeer were kinetic and animated, difficult to imitate, and showed an appreciation of line, color, and form. According to Chesterton, this artistic gift is what makes man stand apart from the animals. “Art is the signature of man,” he says. “It is the simple truth that man does differ from the brutes in kind and not in degree, and the proof of it is here; that it sounds like a truism to say that the most primitive man drew a picture of a monkey and that it sounds like a joke to say that the most intelligent monkey drew a picture of a man.”

Chesterton implies that this unique aptitude bears the mark of a Creator God. We human artists are but apprentices of that greater Artist, God. Makoto Fujimura makes this point explicit in his recent book Art and Faith: A Theology of Making (2021). “Making is the fundamental reality of Homo Faber (man the maker, not just Homo sapiens) and what uniquely defines our role in Creation,” Fujimura writes in that book. “We are Imago Dei, created to be creative, and we are by nature creative makers.”

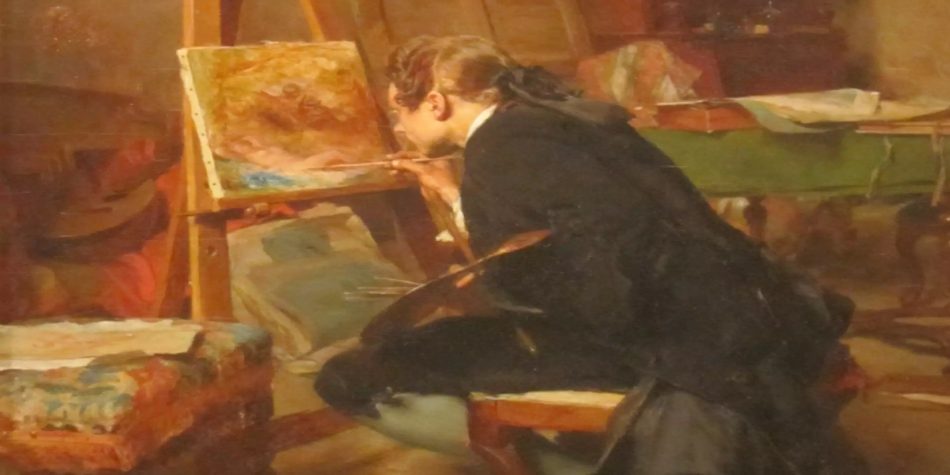

Fujimura, a celebrated Japanese American abstract expressionist artist and devout Christian, has been making art since he was a child. Since childhood, making art has for him been infused with the sacred. “When I painted something as a child, I felt as though an electrical charge were going through me,” he writes. “That energy resounded over the surface of the paper. I thought everyone had this experience. … But these moments of creative discovery seemed sacred to me, even if I did not fully understand them.”

As a child, he did not understand these wild but inarticulable experiences through the prism of Christianity. Now, at 62, he unashamedly uses the lexicon of the Christian to describe his creative inspiration: “Every time I created and felt that charge, I was experiencing the Holy Spirit,” he writes. “I experience God, my Maker, in the studio.” He describes his process of preparing his materials as “liturgical” and imagines that his water-color paints contain “the tears of Christ.” In this sense, Fujimura is a rare specimen in the contemporary art world, having achieved universal acclaim in an arena that is often suspicious, if not downright hostile, to Christian faith.

But the hostility goes both ways. “Imagination, like art, has often been seen as suspect by some Christians who perceive the art world as an assault upon traditional values,” Fujimura writes. “These expectations of art are largely driven by fear that art will lead us away from ‘truth’ into an anarchic freedom of expression. Yet, after many decades of the church proclaiming ‘truth,’ we are no closer as a culture to truth and beauty now than we were a century ago.”

I experience God, my Maker, in the studio.

Fujimura’s book, then, aims to rehabilitate the arts and creativity in Christian communities. His central claim in the book is that creativity and artistic expression are integral parts of faith. “I have come to believe that unless we are making something, we cannot know the depth of God’s being and God’s grace permeating our lives and God’s creation,” he writes. He is skeptical of other, discursive forms of attempting to know God that fall short of the more somatic knowledge gained by making:

Because the God of the Bible is fundamentally and exclusively THE creator. God cannot be known by talking about God, or by debating God’s existence (even if we ‘win’ the debate). God cannot be known by sitting in a classroom, or even in a church taking in information about God. I am not against these pragmatic activities, but God moves in our hearts to be experienced and then makes us all to be artists of the kingdom. The act of making can lead us to coming to know THE creator personally…

Fujimura approvingly cites William Blake, who provocatively claimed that “A Poet, a Painter, a Musician, an Architect; the man or woman who is not one of these is not a Christian.” To both Fujimura and Blake, the person in whom the Holy Spirit is active cannot help themselves from creating—they will be compelled to emulate their Creator God.

Fujimura finds the first evidence for his thesis in the second chapter of Genesis. He delights that God invited Adam to name the animals that He (God) had just made. And, having given Adam the opportunity to exercise his creativity, God honors Adam’s creative act by letting Adam’s names stand. It is Fujimura’s hope that the acts of creativity we perform now will be honored by God and will be made to “stand” into the new world, the Kingdom of God on earth.

Fujimura finds kinship with Bezalel and Oholiab, the architects and designers of the Ark of the Covenant. It is not a coincidence, says Fujimura, that these creatives are the first people in the Bible who are described as having been filled with the Holy Spirit: They are “filled … with the Spirit of God, with wisdom, with understanding, with knowledge, and with all kinds of skills” (Exodus 35:31). These craftsmen had likely learned their craft in Egypt, under slavery, Fujimura points out, but were helped by God to sanctify this pagan training and dedicate their imaginations to a new and holy purpose.

The second reason that artistic creation is central to faith is that it helps us fulfill Christ’s great commission to evangelize the earth. And it may be that art, rather than propositional logic or lectures or sermons, is the most effective force for evangelization: “Some things, of course, are best conveyed in a three-point sermon. But we would lose a great deal if we heard the Good News delivered only as linear, propositional information, for the Gospel is a song.”

It may be that the Good News cannot be captured in our muddy, mortal tongue and that art can better approximate its thrills:

Imagine trying to explain to a flying bird the aerodynamic forces at work when its wings move. Perhaps explaining it undermines the flight itself. Perhaps the effort to understand it will not help the flying at all. This is precisely why artists can open new doors of theological illumination in sharing what Christians call the Good News of the gospel to a world that has only a dim idea, if any, of what is so good about it. Simply by spreading our wings of art to take flight, we “prove” that gravity (or God) exists. When we make, we are taking that flight into the new.

Fujimura’s invitation to Christians is to worship God through making. Through our modest crafts—our sewing, baking, painting, acting, writing, composing—we apprentice ourselves to the great Artist. In doing so, we not only fulfill a great spiritual need for ourselves but also evangelize a world nihilistically convinced of the ugliness of everything.