Hamlet

William Shakespeare

My first substantive encounter with this play came last year. My mother-in-law had died of cancer. My father-in-law had found a second wife within four weeks and was remarried within eight. This has proved to be a blessed union. Yet watching my wife endure what she felt to be the double loss of her mother—first in death, second in her father’s remarriage—helped me better grasp Prince Hamlet’s dark struggle with his father’s death and his mother’s remarriage a month later. To see my wife walk this path was to be in close communion with Hamlet’s lament, “How

weary, stale, flat, and unprofitable, / Seem to me all the uses of this world!”

Granted, our circumstances are quite different than Hamlet’s—no incest or political intrigue or murder here. Even so, the “to be, or not to be” soliloquy of act 3, scene 1, now takes on an even more astounding gravitas for me. When drowning in seas of sorrows, it is suddenly not so strange to follow Hamlet’s logic to at least wish to “take arms against a sea of troubles” and “end the heartache and the thousand natural shocks that flesh is heir to.” The prince’s self-dialogue is gift, an important example of carefully thinking through the consequences of steep actions. It is in doing so that Hamlet describes life after death as:

The undiscover’d country, from whose bourn

No traveller returns, puzzles the will,

And makes us rather bear those ills we have

Than fly to others that we know not of.

“Thus,” he concludes, “conscience does make cowards of us all.” What an exquisite and candid way to voice the burdensome struggles of the soul!

The Lonely Man of Faith

Joseph B. Solovetchik

This essay from 1965 explores the difference between the two Adams of the Book of Genesis. The Adam of Genesis 1 is the “majestic man of dominion and success.” The Adam of Genesis 2 is the “lonely man of faith, obedience, and defeat.” Rabbi Solovetchik saw these not as two different people “locked in an external confrontation,” but as “one person who is involved in self-confrontation.”

Rabbi Solovetchik concludes with a commentary on how the prophet Elisha successfully managed this struggle in his ministry. As the book of 1 Kings tells us, the self-centered farmer Elisha (“remindful of a modern business executive”) underwent a dramatic transformation in response to Elijah tossing him the prophetic mantle.

“Many a time [Elisha] felt disenchanted and frustrated because his words were scornfully rejected. However, Elisha never despaired or resigned. Despair and resignation were unknown to the man of the covenant who found triumph in defeat, hope in failure, and who could not conceal God’s Word that was, to paraphrase Jeremiah, deeply implanted in his bones and burning in his heart like an all-consuming fire. Elisha was indeed lonely, but in his loneliness he met the Lonely One and discovered the singular covenantal confrontation of solitary man and God who abides in the recesses of transcendental solitude. Is modern man of faith entitled to a more privileged position and a less exacting and sacrificial role?”

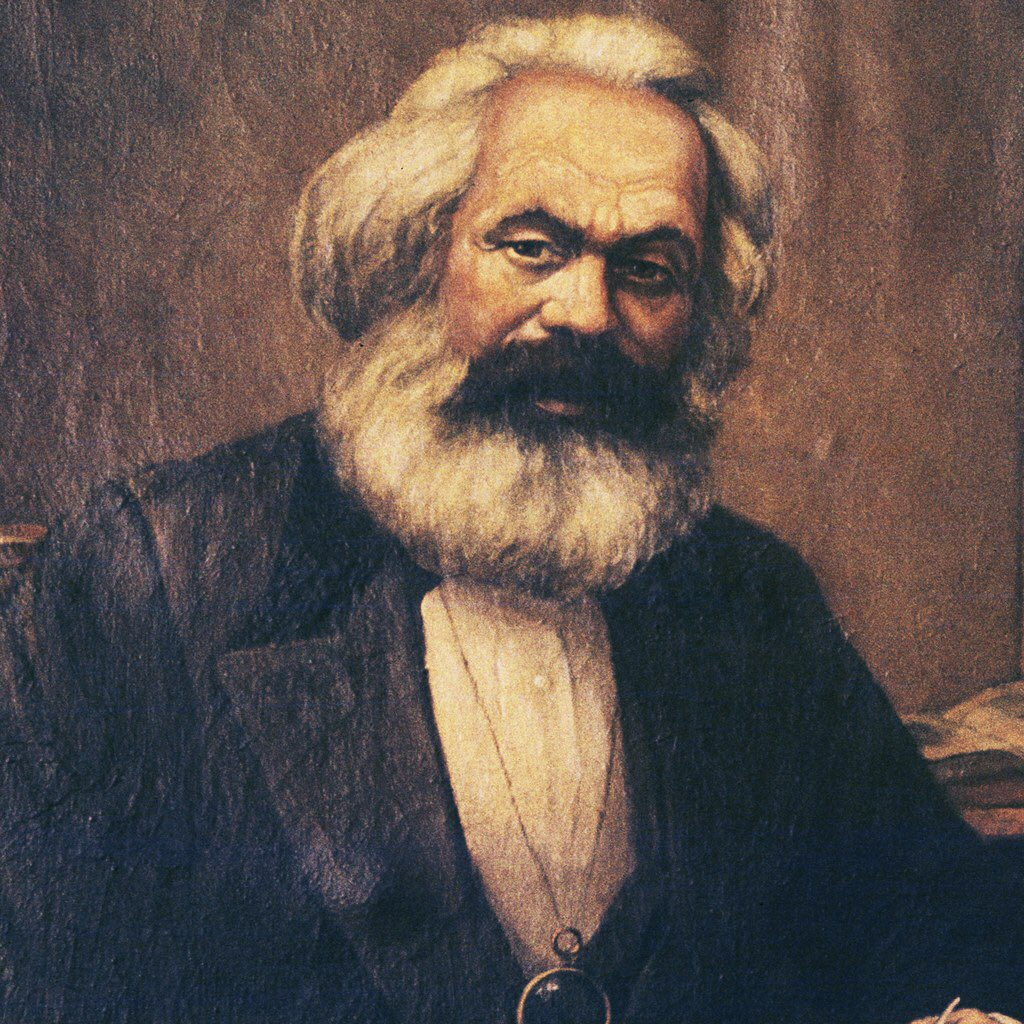

Fathers and Sons

Ivan Turgenev

Ivan Turgenev is yet another Russian author who points us to a bright future of reconciliation—even when looking through tears at a loved one’s headstone. The concluding scene of the 1862 classic “Fathers and Sons” is a mother and father visiting their dead son Bazarov’s grave. He was a nihilist, one who was critical of everything, rejected authorities, and accepted nothing on faith. His parents loved him all the same.

At the grave, they fall to their knees and shed long and bitter tears. “Can their prayers and their tears be fruitless?” the narrator asks. “Can love, sacred, devoted love, not be all-powerful? Oh, no! No matter how passionate, sinning, rebellious is the heart hidden in the grave, the flowers growing on it look at us serenely with their innocent faces; they speak to us not only of that eternal peace, of that great peace of ‘impassive’ nature; they speak to us also of eternal reconciliation and of life everlasting.”

Death on a Friday Afternoon

Richard John Neuhaus

In this extended meditation on Christ’s last words from the cross, the late Catholic priest and founder of First Things magazine hurls bolts of energy at the Christian’s understanding of just who it is that they worship. One striking example from chapter two:

“Christians are often responsible for the common misunderstanding of what is meant when we say, ‘There is salvation in no one else [but Jesus],’ Neuhaus writes. “We are heard to be saying, ‘My truth is better than your truth; my religion is better than your religion (or nonreligion).’ But Christ is not my truth or your truth; he is the truth. He is not one truth among many. He is the

truth about everything that is true. He is the universal and cosmic truth. Everything that is true—in religion, philosophy, mathematics or the art of baseball—is true by virtue of participation in the truth who is Christ. The problem is not that non-Christians do not know truth; the problem is that they do not know that the truth they know is the truth of Christ.”

Church Refugees

Josh Packard and Ashleigh Hope

“I don’t think it’s healthy to just stay inside the walls of a church. Being outside of that structure means having a much broader understanding of the world, a broader vision,” one respondent says

in this study of those who have left churches but held on to their faith in God. “God doesn’t want us walling inside, just being with each other, but that’s what my long experience of church was like. And that would be the other reason I’m very hesitant to ever be a part of a church again, because I don’t want to get stuck inside walls and miss out on all of these relationships that form

the basis of my understanding of God.”

Church Refugees gives voice to those who have left their American Christian church but still have an abiding faith in God. Instead of the “nones” (about whom much has been written), the authors call these people the “dones” or the “dechurched.” Those who still go to church must read slowly and listen with the heart. Others, who have walked away from a congregation, will find comfort in knowing they are not alone.