The first time I learned about neuroplasticity in graduate school, I returned home excited to tell Mary. For years, my sister-in-law had suffered from acute symptoms of depression and anxiety— convinced, like so many others, that this was happening due to biological deficiencies that were both permanent and wholly outside her control.

Was she aware that neuroscientists no longer believed this—and that the updated research not only undermined this prior theory (see here and here and here) but confirmed a much more encouraging understanding of the brain’s role in depression? Surely, I thought, she would be thrilled to hear about the possibility of ongoing brain change throughout our whole lives (See Note #1).

I was wrong. Surprisingly, these revelations brought more distress than comfort to Mary, especially initially—prompting feelings of guilt and questions like: “So, what have I been doing wrong? Then why am I not better yet?”

That was an early lesson for me in the complicated realities of hope—teaching me that even legitimately hopeful messages can sometimes feel not so hopeful (and even threatening), perhaps especially to those grappling with more enduring emotional challenges. An incident this week has been another reminder of this.

New possibilities for healing. This last week, an article I wrote on depression and anxiety went live on the website of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as part of its upcoming July edition of the Liahona, entitled “New Hope for Deeper Healing from Depression and Anxiety.”

I was invited to write the article after presenting preliminary findings from an ongoing qualitative research project at the conference of the Association of Latter-day Saint Counselors and Psychotherapists, entitled “Ten Patterns in Narratives of Sustainable Healing from Depression” (inspired by Dr. Kelly Turner’s similar examinations of patterns in spontaneous remissions of cancer diagnoses).

Over the subsequent year, I worked intensely with a wonderful editorial team to refine it and turn it into a short-form article. How exciting it was to see the finished product finally come out! It felt good to finally be able to share something that wouldn’t be controversial (phew!)—where I could just “share some good news.”

Yet as this week brought home forcefully, this kind of an emphasis on the possibility of deeper healing (and the many ways our own actions can help encourage this) still feels threatening to some. One outspoken critic, in particular, stirred up others with pointed outrage and some ad hominem attacks on my own qualifications to speak on these matters (see Note #2)—while also suggesting that the message of the article could draw attention away from other important considerations.

All this begs the question, what is it that people really need to hear in order to move towards deeper emotional healing?

Hidden burdens in our prevailing mental health conversation. Much of the mental health education work I’ve done over the last 15 years was sparked by a single takeaway from my dissertation research on depression narratives years ago. As we all know, depression can be excruciating. In one interview, a woman compared her experience with depression to earlier acute child abuse:

I have had beatings to the point of unconsciousness—ripped, broken, arms taken out of the socket and that compares nothing—doesn’t even begin to be the pain that became every day, just right here [pointing to her chest]—this thing that wouldn‘t come off, that made it hard to breathe … like, I would rather have every day, just hours of people beating the [crap] out of me than to have been where I was just inside. It hurt that bad; there were times I thought it would kill me—all on its own, that I wouldn’t have to do anything.

The frightening intensity of serious mental illness is what everyone understands. What we don’t understand—and hardly talk about—is the extra burden placed on already vulnerable people when they embrace what is essentially an identitarian narrative of their emotional struggle (“just who I am”), while becoming convinced that these agonizing conditions are inescapably life-long and never going away in any fundamental way.

What are the practical consequences of embracing this particular narrative of mental health? You start to get a glimpse of the answer in comments I’ve heard over and over in interviews:

- “I was told that I had a mental disorder that people never get well from.”

- “The diagnosis I was given … the doctors all through had all said that this was something that was chronic, it was something that was debilitating. It was something that as I got older, it would get worse.”

One woman asked me, “Is there a getting better from this or not? I mean, they told me, in the beginning, there wasn’t. But I’m hoping that I can make improvements that are permanent … I am getting better than I was, certainly. I don’t know how much better, you know?”

I asked her in response, “Who told you that you wouldn’t ever get better?” She responded, “Well, my initial diagnosis, they said, ‘This is something permanent.’ They told me, ‘This isn’t something that you’ll ever not have.’”

I’ve heard the same thing in interviews with parents of teens who were struggling:

- “She will have issues all her life. . . This is a lifelong battle for people with emotional issues.”

- “I don’t think there’s going to be a time that she’s going to be well. We’re going to have to stay on it, stay on it, stay on it forever.”

- “I don’t know how solvable the problem really is.”

- “He needs to learn to live with it the best he can. I’m expecting him to regress. … His brain is wired in a way that his mental illness will be a monkey on his back the rest of his life.”

Laying aside whether this is actually true, imagine a teen hearing that message from a parent or supportive professionals in a vulnerable moment. How would it change how he or she sees who they are and their prospects for happiness in the future?

In fairness, it can be relieving for so many (young and old) simply to have a name for the pain they are experiencing, as well as appreciating possible biological contributors to what’s going on, and moving into a place of acceptance.

For others, however, this can all be a little crushing. I interviewed a young woman who told me that her suicidal thoughts started the same day the doctor told her that her depression would likely be lifelong. Another woman reflected on the moment of receiving her diagnosis, “I was like, ‘this is something that’s going to be with me for good … it’s not a cold that’s just going to go away. This is me,’ you know—and that’s sad. You feel like you lose yourself almost … This is not who I was supposed to be.”

There’s evidence to suggest that those who embrace a view of their own brain as deficient end up seeing their own prognosis as worse and feeling more pessimistic about the potential benefits of other non-medical treatments. Referring to the emotional weight of this narrative, another individual related to me, “When you are already feeling hopeless and in despair, and like, you’ll never get out of the hell you’re in, to have someone tell you that what you have is a condition that you’re going to have to live with the rest of your life, it makes you feel even more hopeless, more in despair, and more worthless, and like, ‘why even try? Why even try? This pain is going to last forever.’” “You feel like you lose yourself almost … This is not who I was supposed to be.”

In addition to the research on brain changeability and epigenetics (what Nobel Prize-winning geneticist Barbara McClintock called the “fluid genome”), there are two large areas of research that back up more hopeful anticipations:

1. Mental health risk factors. One of the pioneering figures in depression recovery, Dr. Neil Nedley, was seeing so many patients come into his practice with depression that he decided to step away and immerse himself in the research literature. What he found astounded him—especially how wide a scope of potential contributors were confirmed in the science. Go ahead and search it yourself: www.pubmed.gov. Last I checked, this is how many scholarly articles came up for:

- Depression” and “risk factor”: 28,424 articles

- “Anxiety” and “risk factor”: 12,170 articles

- “Bipolar” and “risk factor”: 3,358 articles

- “ADHD” and “risk factor”: 2,124 articles

I’ve spent many days poring over this same literature as helpful guidance for new kinds of risk-factor oriented public health initiatives to support people with various mental health challenges. Much like diabetes education programs that help improve the lives of those grappling with that condition, the educational materials and self-assessments we’ve created are designed to help people go deeper in healing (see, for instance, Vulnerability & Strength Inventory for Depression (for adults) and (for children and youth)

2. Therapeutic lifestyle change. In addition to this vast risk factor literature, I’ve been heartened by how many times a single adjustment in a single lifestyle area is again shown to make an incremental but measurable difference in mood. For example:

- As mentioned in the Liahona article, according to a 2021 University of Colorado Boulder, MIT, and Harvard study of 840,000 people published in the Journal of American Medical Association, incrementally adjusting bedtimes earlier makes a difference, with “each one-hour earlier sleep” corresponding “with a 23% lower risk of major depressive disorder.” That means, if someone who normally goes to bed at 1 a.m. goes to bed at midnight instead and sleeps the same duration, they could cut their risk [of future depression] by 23%; if they go to bed at 11 p.m., they could cut it by about 40%.”

- A 2017 controlled study in BMC Medicine by Dr. Felice Jacka and her research team in Australia found that people who changed their diets (and nothing more) were significantly better compared to a control group—with approximately 30% no longer depressed (compared to 8% in the control group).

- Many studies have confirmed the value of physical activity in boosting mood. To cite an early experiment, a group of depressed patients were supported in regularly going on a brisk 30-minute walk or jog around the track three times a week. They ended up with just over 60 percent no longer depressed after 16 weeks (compared with 66 percent taking antidepressant medication), according to a 1999 Duke University Medical Center study.

- Mindfulness meditation has also repeatedly been proven to cut depression relapse in half.

To be clear, none of this suggests people should try to change everything in their life. Rather, it’s about encouraging all of us to think seriously about improving anything in our lives—doing one of the many things documented to make an incremental difference for our mental health.

If single changes can make this kind of a measurable difference, what happens when you combine a number of these same kinds of changes? This is where it starts to get really exciting.

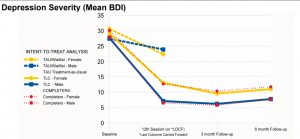

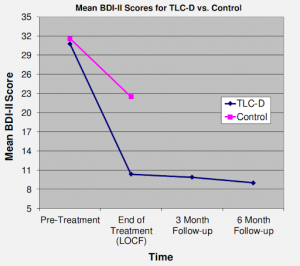

A research team led by Stephen Ilardi at the University of Kansas studied the results of a 14-week (12 sessions) group Therapeutic Lifestyle Change for Depression intervention that helped participants make seven key lifestyle changes (including the four listed above). In 2007, they reported that 68% of participants (55 of 81) had a clinically significant response (50% or greater reduction in depression scores to the point they were no longer clinically depressed) compared to 19% of control group participants (4 of 21). The average decrease of 18 points on the Beck Depression Inventory was a reduction of about 61% from baseline.

But for participants who completed all of the suggested changes, 72% of them (49 of 68) were no longer clinically depressed—with a correlation between how many sessions they attended and how much their scores decreased [see graph below, with the broken line representing the control group and the solid lines the Therapeutic Lifestyle Change (TLC) group].

In a later study, this same team observed clinically significant improvement in 77% of participants in the TLC condition (versus 29% in the treatment-as-usual group).

These are remarkable results, especially when you consider that improvements were maintained at a 6-month follow-up—with no significant relapse after completion of acute therapy (see Note #3).

In addition to all the evidence above, major clinical research findings over the last fifty years have provided increasing cause for hope in the possibility of recovery from even serious mental illness. Summarizing these studies, a 1999 Surgeon General report on mental health stated:

Long-term outcome studies … uncover[ed] a more positive course for a significant number of patients with severe mental illness in populations from virtually every continent, including landmark cross-national studies by the World Health Organization from the 1970s and 1990s, showing unexpectedly high rates of complete or partial recovery.

Reflecting on take-aways of his work, Dr. Ilardi concludes, “Progressive integration of each of these [lifestyle] elements into a multi-component treatment for depression may provide sustainable improvement in depressive symptomatology.” Dr. Jacka went on to call the “scaling up” of these kinds of lifestyle-oriented interventions a “key imperative” in the future. And in his summary review of the impact of these multifactorial mental health interventions, Dr. Roger Walsh of the University of California, Irvine’s College of Medicine concluded that “Lifestyle changes can offer significant therapeutic advantages for patients, therapists, and societies, yet are insufficiently appreciated, taught or utilized.” He then added:

Wide-scale adoption of TLCs [therapeutic lifestyle changes] will likely require wide-scale interventions that encompass educational, mental health, and public health systems. … Given the enormous mental, physical, social, and economic costs of contemporary lifestyles, such interventions may be essential. In the 21st century, therapeutic lifestyles may need to be a central focus of mental, medical, and public health.

The urgency of a new kind of mental health education. All this has been foundational to my own mental health education work over the years. By comparison, most of the mental health education available to families in recent decades has not focused on any of this—not neuroplasticity, not therapeutic lifestyle change, and not mindfulness—far more focused on treatment than what it takes to find more sustainable healing. “In the 21st century, therapeutic lifestyles may need to be a central focus of mental, medical, and public health.” Dr. Roger Walsh, UC-Irvine

This is also why I made the decision in graduate school to be trained as a community psychologist, rather than becoming licensed as a clinical psychologist. No doubt, a good counselor can do miracles. Several of my best friends are amazing therapists. But I’m persuaded by the conclusion of Dr. George Albee in 1959 following his review of the American mental health system, where he stated we will never have enough professionals to put a dent in the scope of mental health challenges facing the nation.

If that was true then, how about now—when wait lists are going up faster than inflation? If we don’t have enough professionals, the good news is we have enough friends, family members, and neighbors—if we can learn to support each other in healing, nurturing community. That is the project that I’ve dedicated my own career as a community psychologist—exploring various ways to encourage, mobilize and empower the precious and fragile networks of relationships all around us, so they can become catalysts to healing, rather than detriments.

Clearly, we can work to increase the capacity of our communities without minimizing the potential benefit of professional support. Let me state that clearly and explicitly: None of the foregoing is “anti-medicine” or “anti-doctor,” since there is an important place for medical support in this picture. When used in appropriate and sensitive ways, it’s true that medical intervention can play a role in someone’s pathway to deeper healing.

My latest work has been implementing this same therapeutic lifestyle approach digital tools like Fortify for sexual compulsivity and Lift for depression and anxiety. While walking people through various focused journeys in the key lifestyle areas, these digital tools help people track ongoing adjustments in key lifestyle areas, while observing the degree to which symptoms (of depression, anxiety, sobriety, etc.) change at the same time. Similar to Fitbit, it can be enormously encouraging for people to see symptoms start to edge upward as they make gradual adjustments to sleep, physical activity, nutrition, stress level, etc. An independent review of data from thousands of app participants by researchers at the University of Alberta and Utah State shows statistically significant improvements in every domain of lifestyle change. These changes happen in a dose-response relationship—with the more people learn and participate corresponding to greater improvements in mood.

I share all this to give some additional context and backdrop for the article, especially since some critics have portrayed this approach as somehow narrowly idiosyncratic to me, rather than representing an enormous amount of empirical backing. “We will never have enough professionals to put a dent in the scope of our mental health challenges facing the nation.”

Got hope? So, what is it that people who are suffering emotionally need to hear the most? That’s clearly a question about which thoughtful people can and do disagree. I’m among those convinced that in our age of metastasizing depression, anxiety, and suicide rates, a message of deeper hope in greater possibilities of healing—yes, going well beyond what any professional treatment might offer on its own —is an urgent need.

In saying this, please know that I feel sincere compassion for those who have grappled over many years (and even decades for some) with significant emotional burdens. None of this is to deny their lived reality, or the possibility of difficult emotional burdens continuing on for many years.

My wife and I are grappling with some of these same questions ourselves with a baby girl who has a brain injury. Will this be a life-long struggle? Will God ask that of us? That’s a question we’re asking—and others have raised in the wake of the Liahona article.

It’s a crucial question and a sacred one—obviously only answerable individually in our own communion with God. I’ll never forget how my own sister-in-law had to ultimately lay aside some of her hopes for deeper healing in this life in order to simply survive in the present. That may be true of many other people as well. I pray we will never forget our central responsibility to minister to the needs of those hurting the most among us.

While doing so, however, it would be a mistake to generalize from these individual cases of longer-lasting affliction to draw broad conclusions for everyone else. If broad-brushstroke conclusions are to be made, we ought to based those on the larger scientific literature. And as illustrated above, by insisting on generalized messaging that convinces people to see their mental and emotional struggles as life-long impairments and disabilities, we may be inadvertently ushering people into a longer-term trajectory of struggle than may be necessary.

Let’s be clear, though: It can be equally problematic to naively paint a picture of rapid healing right around the corner (“as soon as you make serious changes to your nutrition” … “as soon as you boost your physical activity” … “as soon as you start a gratitude diary”). Depression and anxiety are more formidable foes than that—and we shouldn’t pretend that any of our favorite interventions (from meditation to medication) has such distinctive power.

Instead of absolute narratives of endless sickness or soon-to-happen cures, it seems best to simply leave the future open—not foreclosing on surprises that could usher in unexpected new bursts of healing. As one wise woman from Chicago told me in an interview, “never predict the recovery of another person.”

If we have to err on one side, my vote is to err on the side of hope. That’s what I take from those interviewed about their experience of healing—including two who remarked:

- “The important thing is that I know that it won’t last forever. Before, I had no hope. I couldn’t see a light at the end of the tunnel.”

- “Having some hope is crucial to recovery; none of us would keep trying if we believed it a futile effort.”

Another pioneer in mental health recovery, Dr. Daniel Fisher, was told he couldn’t recover after his own diagnosis. He noted: “the belief that one can recover from mental illness is well established as an important aspect of the healing experience,” adding: “This view that if one becomes mentally ill, one will always be sick not only interferes with emotional recovery but also prevents one from identifying as a contributing member of society, striving to return to work, or establishing long-term relationships, which are essential aspects of recovery.”

Referring to interviews he’s done with distressed individuals, Dr. Fisher continues, “Over and over again, we heard, ‘I needed someone to believe in me’”—concluding again: “The most important finding in our research is that people who have shown significant or complete recovery from severe mental illness …. have cited hope as an extraordinarily important component in their recovery. Part of the recovery was being around people who saw their condition as not permanent, a condition from which they could take increasing control of their life and re-establish a place in society” (see Note #4). “The belief that one can recover from mental illness is well established as an important aspect of the healing experience.”

Does that sound at all resonant with the mighty and earth-transforming message of Jesus Christ? A doctrine that encourages all of humanity to reach for mighty changes, ongoing repentance, eternal progression, spiritual rebirths, and yes, miraculous healings?

You bet it does. I rejoice in the Lord who brings to pass—in conjunction with all these many sources of support—true and lasting healing in our lives. For my daughter. And maybe one day for you too.

Notes:

1. Illustrative quotes summarizing neuroplasticity:

- Dr. Jeffrey Schwartz, UCLA Dept. of Psychiatry: “Our physical brain alone does not shape our destiny. How can it, when the experiences we undergo, the choices we make, and the acts we undertake inscribe a diary on the living matter of our cortex? … The life we lead, in other words, leaves its mark in the form of enduring changes in the complex circuitry of the brain—footprints of the experiences we have and the actions we have taken. … It is the life we lead that creates the brain we have.”

- Dr. Louann Brizendine, The Female Brain, 2006: “The brain is … a talented learning machine. Nothing is completely fixed. Biology powerfully affects but does not lock in our reality.”

- Elisha Goldstein, Ph.D., Clinical Psychologist: “It does give people a lot of hope to see a lot of the research coming out, more recently, that says we can grow certain areas of the brain, there’s this idea of neuroplasticity, the idea that we can actually grow important areas of our brain throughout the lifespan now, towards a healthier brain.”

- Amishi Jha, Ph.D., Cognitive Neuroscientist, University of Miami: “What that tells us is that there’s hope—that essentially, you can grow the brain no matter what age you are. And if you can grow the brain, you might be able to have those new neurons connect to existing neurons so that there’s stronger functioning in different parts of the brain. And that gives a lot of hope. If you do a particular activity for some period of time, over and over again, the parts of the brain that are needed for that activity are going to get stronger, are going to get healthier. In the same way that if I were a bodybuilder. If I’m going to work out my upper body, my upper body’s going to be much stronger, but my legs might not change at all. So it’s the activity that we engage in that changes those targeted areas. Same thing for the brain. It wouldn’t surprise anybody to find that if you took somebody that wasn’t very physically fit and took them to the gym … And every day they go to the gym for two months and do a 30-minute workout. It wouldn’t surprise anybody to find that after that two-month period, the person’s more fit, right? They look better, they feel better, their body mass index might have gone down, their weight might have gone down. They have all the signs of being a healthier person, especially if they were not active before. The mind is no different. Just as the brain is fragile and can be damaged, it can actually also be strengthened through active exercise in the same way the body can.”

- Rick Hanson, Ph.D., Neuropsychologist: “Many people, particularly the general public, don’t really appreciate the ways in which mental activity alone—what we think, what we feel, how we guide attention, what we rest it upon, and then what we do with what we’re paying attention to—they don’t appreciate the ways in which that literally sculpts neural structure.” The brain is constantly changing in structure, based on our experiences. If people do the work, if they keep working the muscle, as it were, of the brain, it will gradually change for the better over time.”

2. One critic, in particular, has taken pains to characterize me as a “covid vaccine skeptic” somehow as my primary identity. In America today, of course, that kind of a label is enough to delegitimize anyone. It’s true that like many millions of others in this nation I’ve had questions about the prevailing response to COVID-19. But it’s not true—and a serious and damaging misrepresentation of my public work and writing—to suggest I’ve been a part of undermining and fighting the prevailing public health response. That never felt right to me to engage in. And a closer review of my pieces in the Deseret News, Public Square Magazine, Meridian Magazine, and Millennial Star will confirm that—demonstrating: (1) I’ve never written anything that directly aims to discourage people from vaccination (The one time I wrote most directly about the decision to vaccinate ultimately helped many people follow that prophetic counsel). (2) Everything I’ve written these last two years on the subject centers around either peace-making between various perspectives about COVID-19 or preserving space for people to make their own choices, hardly radical notions.

3. These results have been replicated by others, including Dr. Neil Nedley’s team. But it’s not just mental health where therapeutic lifestyle change has proven itself impressively. In fact, it was cardio-vascular disease and physical health broadly where this approach first began to generate attention—with evidence confirming the reduction in elevated cholesterol, blood pressure, blood glucose, and body fat without medication. Dr. Steven Aldana (my wife Monique’s old boss) conducted a randomized clinical trial with over 300 people who were part of a TLC program (half of the people participated in the TLC program, and the other half waited for six months before they could begin). After learning why and how to have a healthy lifestyle, participants dramatically improved their number of daily fruit, vegetable, and whole-grain servings, and they reduced their intake of saturated fat. They also increased their physical activity by 25%. Aldana was stunned to learn that health risks could improve dramatically in as little as six weeks. Those who maintained healthy behaviors experienced lower health risks for six weeks, six months, 12 months, and even out to 18 months after this program began— reflecting success in participants learning how to adopt and maintain healthy lifestyles successfully. Even better, the individuals who were at risk at baseline and participated in this program saw significant decreases in hypertension, blood cholesterol, and blood glucose. Most of the participants demonstrated significant weight loss as well. This study has been reported in multiple scientific journals.

4. Reference—Medscape, 2005. This doctor goes on to acknowledge the skepticism his own story of healing is usually met with: “We who have recovered from mental illness know from our personal experience that recovery is real. We know that recovery is more than remission with a brooding disease hidden in our hearts. We have experienced healing, and we are whole where we were broken. Yet we are frequently confronted by unconvinced professionals who ask, ‘How can you have recovered from such a hopeless situation?’ When we present them with our testimonies, they say that we are exceptions. … They say that our experience does not relate to that of their seriously, biologically ill, inpatients” (National Empowerment Center, 2010).