“Interrogate your hidden assumptions.” — Cornel West

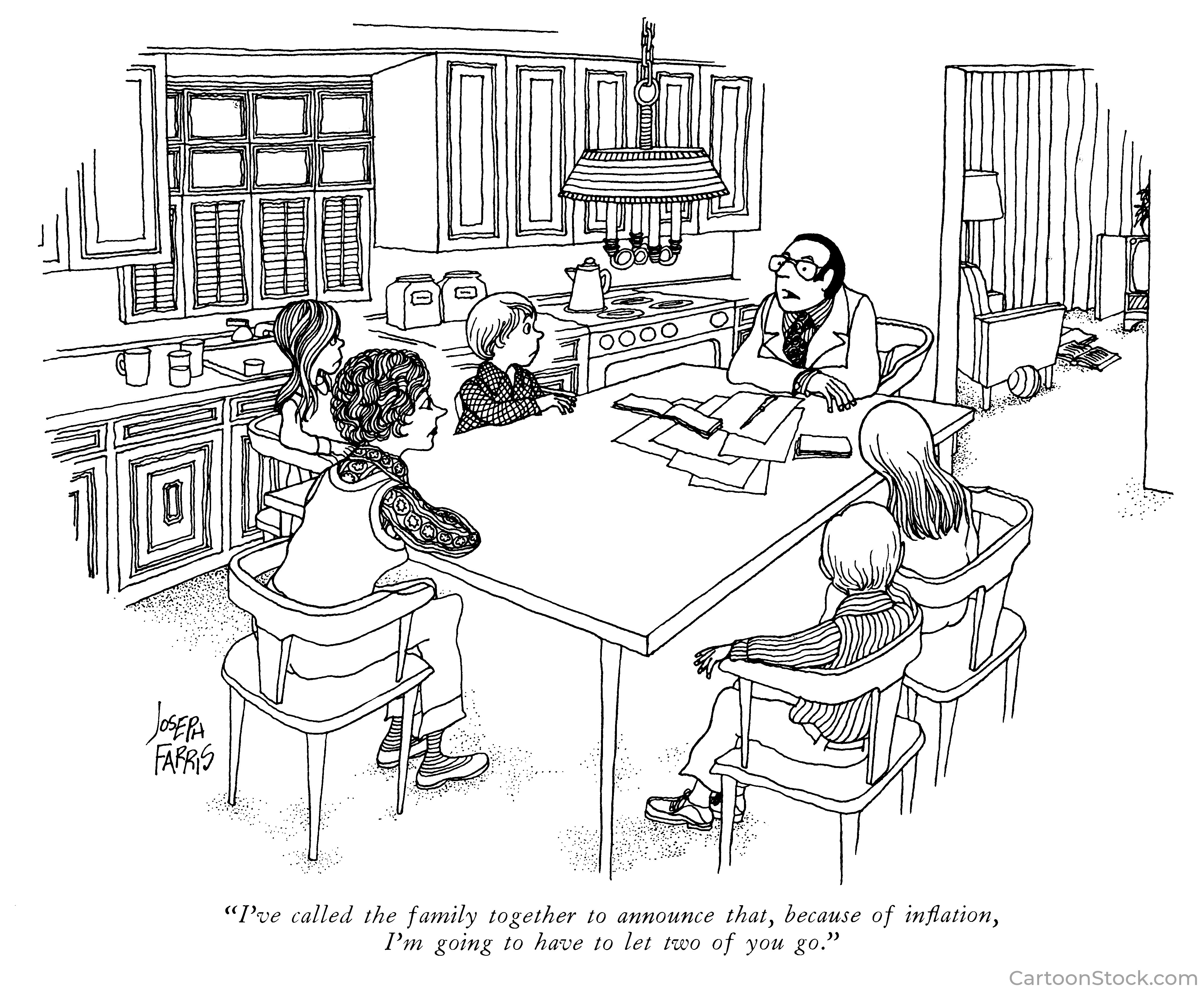

We are now living, it appears—or so we are told by a growing number of cultural commentators—in a “post-truth era” or an “age of doubt,” a world where all the old certainties are now up for endless debate, skeptical scrutiny, and deconstruction. It often seems as if the world is every day becoming more and more a place where the unquestionable truths held firm by previous generations are taken to be hopelessly mired in bias and contradiction, nothing more than the socially constructed products of particular economic and social interests, cultural interpretations, and political power grabs.

The 19th century German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche perhaps saw most clearly our current situation when he spoke of a world populated by those who are such “admirers of mystery and the unknown, that they worship the question mark itself as their god.”

Unsurprisingly, the truth claims of traditional religious faith and practice have received special critical attention in our newly emerged world of uncertainty and deep questioning. Indeed, as one religious leader recently observed, “There are few members of the Church who, at one time or another, have not wrestled with serious or sensitive questions.” This kind of careful and probing questioning of one’s own beliefs and religious commitments, of course, need not be understood as an essentially negative or faith-corrosive endeavor. As the theologian Matthew Lee Anderson suggests, “Questioning is a form of life, a habit, and even a disposition. It is one way our loves and desires take shape—and a practice that also shapes our desires.” Likewise, Liberty University English professor Karen Swallow Prior notes in a recent book, “Scrutiny can be evidence of a living faith—one that is active, growing, and bearing fruit . . . a faith that never feels challenged is most likely dead.”

“Questioning is a form of life, a habit, and even a disposition.”

There is, of course, an important distinction between thoughtful questioning, even of one’s most cherished and foundational beliefs, on the one hand, and doubting for the sake of doubting on the other. Doubt unguided by humility and thoughtful reflection is simply an indulgent exercise in pseudo-intellectual skepticism. Sincere questioning, in contrast, is a matter of intellectual responsibility. As ordained minister and biomedical research scientist Christina M. H. Powell makes clear, religious believers, especially Christians, “must be willing to face the difficult questions about their faith. However, intellectual responsibility also requires a commitment to question doubts in all the various forms they may arise.”

In other words, genuinely responsible and intellectually honest questioning of one’s religious beliefs, including the truth claims of one’s religious tradition, demands not simply entertaining, or even obsessing about, doubts about the trustworthiness of such things, but a genuine openness to critically reflecting on those doubts, their origins, and the (frequently hidden) assumptions upon which such doubts are often based.

Before proceeding, however, it is necessary to first dispel a common misconception about faith and the struggle for understanding. Sometimes it is easy to assume that anyone beset by doubt or experiencing a crisis of faith must be doing so because they have committed some sort of sin, allowing themselves to be drawn away from the light of truth and into confusion because of indulgence in one or another act of proscribed wrongdoing. The presumption seems to be that the only reason the doubter is doubting is because it promises to make an appropriately felt sense of guilt or unworthiness go away. From this vantage point, doubt is primarily driven by a deeper desire to get oneself “off the hook” for one’s sins by finding a way to escape rightful punishment.

Unfortunately, while there may be cases in which this understanding holds true, it is, I suspect, far from typical or necessary. As with so much in life, things are simply not that simple.

Over the years, many of my friends and family have experienced periods of doubt—often intense—about their religious beliefs, scriptural doctrines, and Church teachings. In some instances, there were clear signs that these individuals were living their lives in ways that alienated them from the Spirit of God. In one or two cases, they had simply chosen to take offense at something a particular Church leader or fellow believer had said or done. More frequently, however, the seeds of doubt were primarily intellectual in nature. Now, that does not mean that the seeds of their doubts were always the result of careful scholarship or the best thinking and analysis. It only means that their concerns and questions were not intrinsically rooted in some moral failing or rebellious and sinful desire.

I have had friends, for example, who found themselves questioning their faith when they discovered that certain sacred religious practices had changed over the course of time. Others began to question their faith when they encountered statements made by previous Church leaders that seemed to contradict current Christian teachings, and vice versa. Yet others I know and love found their faith in question when they learned that a particular teaching they thought was theologically sure and certain turned out to be nothing of the sort, more a matter of policy than enduring doctrine. I have also watched, especially in recent years, as some of my friends have called into question the authority of religious leaders, and even scripture itself, because of particular teachings on sexuality, marriage, abortion, or other controversial political topics. There are other friends of mine who began to doubt their faith because they could not seem to find a way to reconcile the latest theories and findings of science with the scriptural teachings they had grown up learning and believing. And, finally, I am acquainted with some whose doubts are the manifestation of their deep dissatisfaction with the hierarchical and authoritative structure of the Church, something they feel places unnecessary and burdensome constraints on the expression of their individual freedom and agency.

I am convinced that many of the questions that so frequently seem not to have any answers . . . only seem so because they are approached from the wrong premises.

Unfortunately, these few examples do not exhaust the issues and concerns that I have witnessed family members, friends, colleagues, students, and neighbors struggling with over the years—though I sincerely wish it did. I know their pains and frustrations are very real, that the bouts of mental and emotional anguish, the gnawing doubts, and the frustrations that fueled so many sleepless nights are no mere affectations, but in fact are very real. That said, however, I believe that in a great many of these cases, the faith crises my friends and loved ones were undergoing were in large measure unnecessary and avoidable—though perhaps not easily, and not without serious effort being made. You see, many of the questions and doubts that constitute the essential “stuff” out of which so many faith crises spring do so from a common (though often hidden) source. I am convinced that many of the questions that so frequently seem not to have any answers—or that seem only to have answers that end up in a diminished faith or in abandoning religious belief—only seem so because they are approached from the wrong premises. In other words, I do not believe it is the particular questions we have regarding our faith—or even the fact of entertaining questions in the first place—that is the most central problem here. Rather, I would like to suggest that the real problem we face is to be found in the taken-for-granted secular assumptions that lie at the root of so many of our doubts and questions, and which subtly but profoundly frame how we think about such things as God, sexuality, agency, science, reason, history, culture, and the nature and meaning of faith and truth.

While the doubts and struggles so many have as they try to make sense of their faith, of scripture, and of prophetic teachings are clearly both authentic and agonizing, perhaps the real source of frustration and confusion is that they are looking for the corner of a round room. The influential historian Robert Louis Wilken once wrote, “Christianity is more than a set of devotional practices and a moral code: it is also a way of thinking about God, about human beings, about the world and history.” Unfortunately, in our increasingly secular and religiously illiterate society, the way in which religious faith and ritual offers not merely a set of prescribed and proscribed practices and statements of belief, but also (and most importantly) a distinctive and textured way of making sense of ourselves, God, our world, and our place and purpose in it is often lost and underappreciated. As a comprehensive and coherent worldview, and one that stands in stark contrast to that of secularism, Christianity (understood broadly) provides a very different intellectual foundation upon which to think deeply about who and why we are. To paraphrase Elder Dallin H. Oaks, a senior apostle of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, on a great many important issues, a Christian worldview simply allows for us to think differently. That is not to say that “we have a different way of reasoning in the sense of how we think,” but rather that “on many important subjects our assumptions—our starting points or major premises—are different from many of our friends and associates.” Indeed, taking some time to consider just how differently we think within a broadly Christian, religious worldview—and how such different thinking can help us navigate the challenges of living in a “post-truth world” to find some resolution to the crises of faith that plague us in our “age of doubt”—is the central purpose of this series of short essays.

In that light, then, I would like to extend an invitation to consider that many of our most basic beliefs as Christians actually hinge on very different premises than the ones we may have unwittingly absorbed from our larger, secular world through our everyday engagement with and immersion in it. And, because this is so, the premises of our questions about those beliefs, begetting as they so often do deeply painful crises of faith, matter very, very much. In other words, if the premises out of which our doubts flow are inadequate to the task of understanding the nature and meaning of our religious beliefs and practices in the first place, then perhaps we might avoid finding our faith in crisis if we paid more attention to the alien, often toxic, nature of those premises. In short, I want to open a space in which we can step back a bit and “doubt our doubts” before giving up on our religious faith and commitments by more carefully and critically examining some of the unquestioned “secular certainties” upon which so many of our doubts and concerns are founded. If it should turn out that those certainties are less than certain, less than the solid and stable foundation we tend to naively take them to be, then it might just be that there is a way out of what otherwise seem like insoluble conundrums.

“For Christians, thinking is part of believing.”

Over the course of subsequent essays in this series, a central and sustaining theme will be that the questions and doubts at the root of so many of our contemporary crises of faith must be met by more sustained and careful reflection on the premises from which they spring. In order to do this successfully, we must be willing to not only critically examine and interrogate the assumptions upon which doubts are founded, but also thoughtfully and honestly consider the alternative assumptions and starting points upon which faith is founded. This is really nothing more than an invitation to critical reflection and questioning—or, in other words, thinking: thinking about faith, thinking about God, thinking about truth, and thinking about those things we take to be true but question, as well as those things we take to be true but seldom question.

Finally, it must be remembered that embracing doubt simply because something or someone can be doubted is not really thinking, though it far too often passes for such in our world these days. Rather, such doubting is really just intellectual laziness masquerading as critical thinking, and, as such, it demands far, far too little of us, either in mind or spirit. Engaging in the strenuous work of genuinely and honestly probing of one’s beliefs and ideas by critically reflecting on the presuppositions of those questions, while at the same time seriously entertaining the possibility that there might be more, even far more, to the Christian worldview than might have previously been supposed, is the essence of what I mean here by thinking. As Robert Louis Wilken also wrote, whether in the vise-grip of doubt or comfortably confident, “For Christians, thinking is part of believing.” My sincerest hope is that by engaging in some critical reflection on the likely sources of the expanding number of doubt and faith crises—critical reflection grounded in and enlightened by the Christian worldview—we may come to see what the real and most fundamental difference is between secular starting points and sacred ones. Perhaps, in the end, we may come to see that Christ Himself is the only foundational premise that makes any real sense.