As the house quieted down after a busy Sunday dinner, I got my laptop out to watch the young adult devotional that had been broadcast earlier that evening. I was eager to listen to Elder David A. Bednar’s address, “Things as They Really Are 2.0,” because his message had been so prophetic fifteen years earlier. What would he say now?

As Elder Bednar discussed both the possibilities and the perils of modern technology, I was taken aback when he said:

Consider the following perilous possibility. An AI-developed companion, a girlfriend or boyfriend, can be ‘meticulously designed to [offer] engaging and addictive experiences, appealing to a wide range of emotional and social needs.’… The allure is further heightened by their 24/7 availability and the absence of the complexities often found in [authentic] human relationships…Counterfeit emotional intimacy may displace real-life emotional intimacy—the very thing which binds two people together.

My husband had been reading nearby but put his book down when he heard this. We exchanged bewildered looks and questioned if this was really a problem. With a heaviness, my husband said, “It must be if Elder Bednar is talking about it.”

We live in perplexing times, and even though Elder Bednar offered reassurance, his prophetic warning felt serious as a definite theme emerged—we must be on guard so we aren’t “transformed from agents who can act into objects that are only acted upon.” He repeated a variation of this phrase nine times, and when specifically discussing AI companionship, he said, “It is a set of computer equations that will treat you as an object to be acted upon, if you let it. Please, do not let this technology entice you to become an object.”

Elder Bednar then taught something familiar but new in the way he applied it to the challenges of our day. He said,

The fundamental purposes for the exercise of agency are to love one another and to choose God. Consider that we are commanded—not merely admonished, urged, or counseled—but commanded to use our agency to turn outward, to love one another, and to choose God [Emphasis added].

Using our moral agency to choose God and to love others is the purpose of our mortal existence, and we need to turn outward to do those things. This seems obvious, but if we are being warned so strongly by an apostle, it must be that the enticements to turn inward are so pervasive and the counterfeits so deceptive that they are successfully undermining human agency.

Consider similar warnings against turning inward that were given at our most recent General Conference. Elder José A. Teixeira said:

When our lives are filled with purpose and service, we avoid spiritual apathy; on the other hand, when our lives are deprived of divine purpose, meaningful service to others, and sacred opportunities for pondering and reflection, we gradually become suffocated by our own activity and self-interest …[Emphasis added].

Elder Ulisses Soares taught:

[There is a] current growing trend in the world, adopted by so many, of people becoming consumed with themselves …This way of thinking is often justified as being “authentic” by those who indulge in self-centered pursuits [and] focus on personal preferences … My dear friends, when we choose to let God be the most powerful influence in our life over our self-serving pursuits, we can make progress in our discipleship and increase our capacity to unite our mind and heart with the Savior. [Emphasis added].

And Elder Bednar warned:

We always must be on guard against a pride-induced and exaggerated sense of self-importance, a misguided evaluation of our own self-sufficiency, and seeking self instead of serving others.

As we pridefully focus upon ourselves, we also are afflicted with spiritual blindness and miss much, most, or perhaps all that is occurring within and around us. We cannot look to and focus upon Jesus Christ as the “mark” if we only see ourselves. [Emphasis added].

Using our moral agency to focus outward on God and on others is a protection against suffocating self-regard.

These warnings of church leaders bring to mind the great Jewish thinker Martin Buber (1878-1965), who voiced similar concerns. Buber cautioned against the objectifying tendencies that have accompanied scientific advancements. While he expressed appreciation for the good that has come with progress, he also warned about the possible negative impacts on relationships.

Buber explored human relations through his theory of dialogue, in which he differentiated I-Thou from I-It relationships. He focused on the way in which each of us, as the “I,” relate and communicate with the other. There is a difference between the “I” who interacts with the other as a Thou in contrast to the “I” who interacts with the other as an It. Buber explained, “The primary word I-Thou can only be spoken with the whole being. The primary word I-It can never be spoken with the whole being.” In I-It relations, the ‘I’ looks to the other as an object, and the interaction takes place within the ‘I.’ In I-Thou relations, the subject-object dichotomy is overcome.

In genuine dialogue, when the other is recognized as a Thou, there is an understanding of the other as an individual while, at the same time, sharing an intimacy with them. In such a relationship, there is genuine effort to balance the contradictory expectation of an individual retaining personal uniqueness with the expectation that there will also be a sharing of each other in dialogue. “The real self appears only when it enters into relation with the Other. Where this relation is rejected, the real self withers away…”

There is a pessimism in Buber’s writings as he observed that humans often fall short of I-Thou relations:

In our age, the I-It relation, gigantically swollen, has usurped, practically uncontested, the mastery and the rule … this I that is unable to say Thou, unable to meet a being essentially, is the lord of the hour. This selfhood that has become omnipotent, with all the It around it, can naturally acknowledge neither God nor any genuine absolute which manifests itself to men as of non-human origin. It steps in between and shuts off from us the light of heaven.

In Buberian thought, if we are unable to enter I-Thou relations with one another, we are also unable to enter relations with God. Buber continues,

Life cannot be divided between a real relation with God and an unreal relation of I and It with the world—you cannot both truly pray to God and profit by the world. He who knows the world as something by which he is to profit knows God also in the same way.”

Conversely, however, if we seek a renewal of relation between humans, we will also experience relation with God. God transforms human beings “from self-centeredness to relationship-centeredness,” and it changes the obsession with the self into a genuine and renewing relationship with God and others.

Buber’s dialogical theory underscores Elder Bednar’s warnings about being transformed into objects that are acted upon. With the incredible advances in communication technology since Buber’s death, it is fascinating to imagine the heightened cautions he would now give.

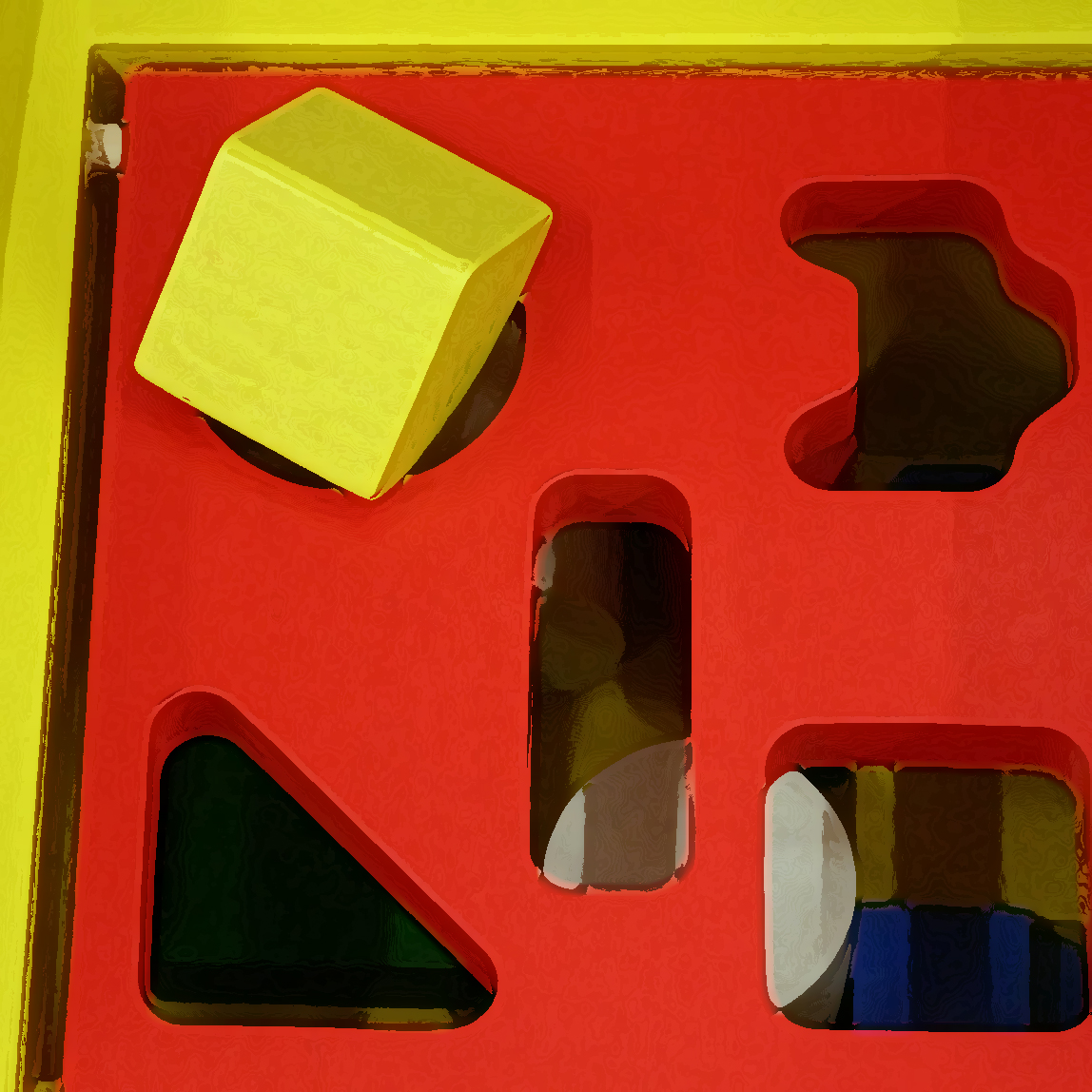

It is sobering to think how our relationships can potentially be harmed. AI companions may not be the thing that entices us, but there are many other ways in which real human interactions, with their attendant complexity, can be replaced by simpler imitations. This goes so much deeper than wasting time on our phones to the neglect of family members, replacing in-person interaction with social media, or only seeking affirming voices online. It is those things, but it is also much more fundamental. It strikes at the core of who we are as human beings who need to be in real relation with one another.

To better understand how objectification hurts individuals and their relationships, we can look at the uniquely powerful example of human sexuality. This most intimate of relations has the potential to profoundly bring a husband and wife together, or conversely, it can alienate men and women from one another. C.S. Lewis masterfully addressed what is lost when sex is used for one’s own use. His description predates the digital age with its easy access to pornography, but it becomes more meaningful, not less, when applied to our day. The temptation to turn inward has always existed, but it is heightened by virtual reality. He said:

For me, the real evil of masturbation would be that it takes an appetite which, in lawful use, leads the individual out of himself to complete (and correct) his own personality in that of another (and finally in children and even grandchildren) and turns it back; sends the man back into the prison of himself, there to keep a harem of imaginary brides.

And this harem, once admitted, works against his ever getting out and really uniting with a real woman.

For the harem is always accessible, always subservient, calls for no sacrifices or adjustments, and can be endowed with erotic and psychological attractions which no woman can rival.

Among those shadowy brides he is always adored, always the perfect lover; no demand is made on his unselfishness, no mortification ever imposed on his vanity.

In the end, they become merely the medium through which he increasingly adores himself … After all, almost the main work of life is to come out of our selves, out of the little dark prison we are all born in. Masturbation is to be avoided as all things are to be avoided, which retard this process. The danger is that of coming to love the prison.

Lewis’ description is powerful, and while his focus is the male viewpoint, women are also susceptible to counterfeits which offer to fill needs without the demands of real human interaction. The enticement of fake companionship, whether emotional or physical, is something everyone needs to guard against.

There is a shared heaviness in these various warnings that I’ve mentioned, and it’s easy to feel discouraged or even alarmed, but Elder Bednar promises that there aren’t just perils but also great possibilities in this “remarkable season of the dispensation of the fulness of times.” As we use our agency to turn outward, we will be able to resist perilous self-focus, but we desperately need one another to do this. In the busyness of life, we may think at times that the toddlers at our feet, the youth we serve, the neighbors we share a fence with, the man full of answers in Sunday School, our co-workers, and our spouses are roadblocks to attaining our personal goals. They aren’t. They are the reason we are here on earth. Amidst the complexities of life, there is great sweetness, meaning, and growth to be found in relation with God and others.

So many voices call to us with the ‘how-to’ of living our best life. The ones to pay attention to are those undergirded by the command to “use our agency to turn outward, to love one another, and to choose God.”

For “Every particular Thou is a glimpse through to the eternal Thou.”