There is a disconnect between the coalition of Trump supporters—including everyone from his most ardent fans to the least-enthusiastic, “lesser-of-two-evils” cynics—and the #NeverTrump conservative opposition. The disconnect stems from fundamentally different ways of thinking about the election. For the most part, Trump supporters apply conventional policy analysis. In this regard, Trump is actually in a slightly better position in 2020 than he was in 2016. His political philosophy may be as hard to pin down as ever, but now he has a track record, and in at least a few crucial ways (e.g. Supreme Court nominations) that track record is as good as any conservative could hope for from a President.

While the #NeverTrump opposition certainly has a list of policy disagreements, any debate on those terms is doomed to acrimonious failure because over on the #NeverTrump side the policy analysis is secondary. Even their (I should say: our) complaints about Trump’s fitness for office—while sincere and important—do not get to the heart of the matter. As a #NeverTrumper myself, I have wasted a lot of my time and everyone else’s because I haven’t fully realized just how true this is. My interests in policy and character are sincere and deeply held, but ultimately the core of #NeverTrump opposition isn’t about either of those things. It’s about something more important and more abstract. It’s about the nature of the United States as a liberal nation.

What is Liberalism?

Before we go any farther, it’s essential to provide a working definition for “liberalism.” For many people, “liberalism” is associated with the Democratic Party and the American left more broadly, but the sense I have in mind is much older and less partisan. Scott Alexander, writing for his influential blog Slate Star Codex in 2017, provides a good example of the definition I am using:

People talk about “liberalism” as if it’s just another word for capitalism, or libertarianism, or vague center-left-Democratic Clintonism. Liberalism is none of these things. Liberalism is a technology for preventing civil war. It was forged in the fires of Hell—the horrors of the endless seventeenth-century religious wars. For a hundred years, Europe tore itself apart in some of the most brutal ways imaginable—until finally, from the burning wreckage, we drew forth this amazing piece of alien machinery. A machine that, when tuned just right, let people live together peacefully without doing the “kill people for being Protestant” thing. Popular historical strategies for dealing with differences have included: brutally enforced conformity, brutally efficient genocide, and making sure to keep the alien machine tuned really really carefully.

By “making sure to keep the alien machine tuned really really carefully,” what Alexander means is that liberalism relies on a suite of formal and informal institutions (like laws and cultural assumptions that work together to support free speech in practice) that are constantly under threat from either the left or the right. In the case of free speech (just as one example), we constantly have to remind ourselves—and both sides—that the point of free speech is to enable speech we disagree with, and resist the temptation to try and suppress what our opponents want to say. This requires constant negotiation and renegotiation of both formal laws, policies, and regulations and informal social norms. Liberalism is an unstable equilibrium. It’s not self-perpetuating. Without constant support and adjustment, it will invariably give way to older forms of human government, all of which are predicated on coercive conformity and incompatible with peaceable diversity.

The most striking thing to me about Alexander’s definition is that while it seems a little irreverent and comes from an amateur, anonymous blogger it aligns quite squarely with Francis Fukuyama‘s definition in a piece for American Purpose just a couple of weeks ago:

Classical liberalism can best be understood as an institutional solution to the problem of governing over diversity. Or to put it in slightly different terms, it is a system for peacefully managing diversity in pluralistic societies. It arose in Europe in the late 17th and 18th centuries in response to the wars of religion that followed the Protestant Reformation, wars that lasted for 150 years and killed major portions of the populations of continental Europe.

From an American perspective, liberalism found its purest expression in the founding of our nation. Writing for The Atlantic in 2018, Amy Chua and Jed Rubenfeld expressed this view:

For all its flaws, the United States is uniquely equipped to unite a diverse and divided society . . . America is not an ethnic nation. Its citizens don’t have to choose between a national identity and multiculturalism. Americans can have both. But the key is constitutional patriotism. We have to remain united by and through the Constitution, regardless of our ideological disagreements.

That is to say, the Constitution of the United States is a deliberate and explicit attempt to instantiate the hard-won ideas of liberalism in the operating system of our country at the deepest possible level. America is, in this conception, a monument to liberalism. And “constitutional patriotism” may as well be read: loyalty to liberalism.

I was astonished to see just how forcefully this view of liberalism and its connection to America was promulgated in the most recent General Conference of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Reverence for the Constitution goes back to the days of Joseph Smith and is a well-known distinction of the Latter-day Saint faith, so there wasn’t anything groundbreaking in Elder Quentin L. Cook’s reaffirmation that “In our doctrine, we believe that in the host country for the Restoration, the United States, the U.S. Constitution and related documents, written by imperfect men, were inspired by God to bless all people.”

What made this General Conference different, however, was that for the first time the leaders of my church went farther and tied reverence for the Constitution to the liberal principles of tolerance and diversity. A lot of this was implicit in the frequent and consistent discussion of diversity and culture, but President Dallin H. Oaks made it explicit in his talk, Love Your Enemies.

The United States was founded by immigrants of different nationalities and different ethnicities. Its unifying purpose was not to establish a particular religion or to perpetuate any of the diverse cultures or tribal loyalties of the old countries. Our founding generation sought to be unified by a new constitution and laws.

Then he cited the exact same passage from Chua’s and Rubenfeld’s Atlantic piece that I did just a few paragraphs earlier.

In decades past, conservative Christians (including Latter-day Saints) could depend on a close correlation between their values and those of the Republican Party. The inertia of this cooperation cannot blind us to the very real divergence we are witnessing. Conservative Latter-day Saints in particular must not dismiss as meaningless, rhetorical concessions of convenience the frequent references to diversity and multiculturalism in the most recent General Conference. Elders Cook and Oaks and others mean what they say.

Although I was surprised by the directness of the defense of liberalism, perhaps I shouldn’t have been. Liberalism is the child of Christianity. Its central tenets—universal human dignity and tolerance —derive from Christian theology and tradition. Elder William Jackson taught this in The Culture of Christ, referencing the definitive conflict between Gentile and Jewish cultures in the first generation of Christians. Out of Paul’s inspired resolution to that conflict, we learned:

We can, indeed, all cherish the best of our individual earthly cultures and still be full participants in the oldest culture of them all—the original, the ultimate, the eternal culture that comes from the gospel of Jesus Christ.

This is the heritage of all Christians, as David French (who is an evangelical Christian) exemplified in a recent essay: “Your commitment to Christ is permanent, eternal. Your commitment to a party or a politician is transient, ephemeral.”

I wish to be clear about the limits of what I am claiming. Based on the history and theology of Christianity along with the specific teachings of LDS leaders, we should acknowledge that liberalism (as defined here) is divinely inspired.

But that doesn’t tell us how to vote.

The ideals are pluralism and tolerance, the dream that different people can live together in peace despite their differences.

Liberalism is not the only sacred value in play, here. Another even more important value (to name just one) is the sanctity of human life. With the nomination of Amy Coney Barret, President Trump may very well be instrumental in bringing about the end of the Roe-v-Wade and allowing the American people a chance to enact laws that respect the sanctity of human life.

How do we balance these competing values? We have to not only weigh their relative importance, but also make a whole host of practical inferences, guesses, and assumptions. All of these fall outside the clear implications of Christian faith. Having made the case that liberalism is inspired, from here on out I am going it alone and do not claim to have Christianity in general or LDS General Authorities in particular on my side. The rest of the case is mine to get right or wrong.

So liberalism, then, is both a set of ideals to which we aspire and a set of institutions and norms intended to implement, at least partially, those ideals. The ideals are pluralism and tolerance, the dream that different people can live together in peace despite their differences. The institutions and norms to instantiate this dream (even imperfectly) include an emphasis on rule of law (especially Constitutional law) that privileges process over outcomes, along with specific civil liberties that are enshrined in both law and custom, and finally an accompanying culture that regards peaceful disagreement and voluntary rule-following as civic virtues.

For the most part, this project has been wildly successful and viewed as incontestably worthwhile, but that is no longer universally the case. Liberalism, like any good compromise, fully satisfies no one. Both the left and the right have their reasons to be skeptical of liberalism and, in recent years, that skepticism had grown to outright hostility, especially from the progressive left.

The most prominent recent example is the New York Times’ controversial 1619 Project. As covered by Daily Kos in 2019,

The 1619 Project is a major initiative from The New York Times observing the 400th anniversary of the beginning of American slavery. It aims to reframe the country’s history, understanding 1619 as our true founding, and placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of the story we tell ourselves about who we are. [emphasis added]

(I linked to Daily Kos because the NYT, under fire for historical inaccuracies, has been trying to retroactively fix the 1619 Project, up to and including a denial of the whole Project’s raison d’etre: to repudiate America’s liberal foundations and recast the country as originally, unquestionably, and irredeemably racist.)

Illiberalism is on the rise on the right as well, as we will see later in this piece.

Secularism and the Progressive Left

According to Fukuyama, the left is historically dissatisfied with the way that liberalism’s necessary defense of private property (see above, re civil liberties) has led to an exaggerated and unnecessary fervor for deregulation that, in turn, drives spiraling economic inequality.

The right’s historic dissatisfaction, by contrast, is that liberalism’s primary mechanism for allowing peaceful pluralism is “to lower the temperature of politics by taking questions of final ends off the table and moving them into the sphere of private life.” What this means is that questions of ultimate meaning—like the correct idea of human nature or the proper definition of a good life—are excised from the political institutions that have universal authority and removed to voluntary religious institutions (or no institution at all).

The alternative, to leave the question of final ends in the hands of the state, makes pluralism impossible because whichever religious or political persuasion dominates the state has the chance to co-opt the state’s coercive power on behalf of their ideology, kicking off an existential struggle to control the state. The only long-term solution in this scenario is endless balkanization into ever smaller and more homogeneous sub-states or some variant of ethnic cleansing. (Note, these two concepts are exactly the specters that most concern watchers of American politics today: secession and civil war.)

Stripping the government of its power to dictate “final ends” short-circuited this process. It enabled Catholics and Protestants to start coexisting peacefully in the 17th and 18th centuries and it continues to allow religious, ethnic, and political diversity in modern liberal states. However, as Fukuyama notes, it leaves dissatisfied those religious individuals who yearn to see their beliefs and values reflected back at the highest levels of society.

Thus, according to Fukuyama’s analysis, we would expect left-originating attacks on liberalism to have a distinctly economic concern. But that’s not what we’re seeing today. Instead, contemporary social justice is based on identity (race, gender, and sexual orientation).

This is not to say that the progressive left accepts capitalism (an inseparable partner of liberalism due to liberalism’s guarantee of private property as one of the core civil liberties). On paper, at least, they find capitalism just as loathsome as ever, and income inequality is also often cited as an outrage. However, both capitalism and income inequality are increasingly seen as secondary symptoms of the true evil: white supremacy, patriarchy, homophobia, and transphobia.

Thus, citing Fukuyama again:

Many progressives on the left have shown themselves willing to abandon liberal values in pursuit of social justice objectives. There has been a sustained intellectual attack on liberal principles over the past three decades coming out of academic pursuits like gender studies, critical race theory, postcolonial studies, and queer theory, that deny the universalistic premises underlying modern liberalism.

In other words, liberalism raises universalistic premises that are not always met in the messiness of real life—especially historically—and that gap continues to lead to impatience with liberalism itself. There’s certainly truth to that, but what the analysis misses is the fundamentally religious nature of the progressive left’s illiberalism.

John McWhorter has been one of the most trenchant observers of this strange phenomenon, although it’s widely known enough that the entire progressive left’s anti-racist ideology has been nicknamed “the Great Awokening” as a parody of the historical American religious revivals known as Great Awakenings.

Here is McWhorter for the Daily Beast in 2017 defending his assertion that anti-racism is a religion:

Of course, most consider antiracism a position, or evidence of morality. However, in 2015, among educated Americans especially, Antiracism—it seriously merits capitalization at this point—is now what any naïve, unbiased anthropologist would describe as a new and increasingly dominant religion. It is what we worship, as sincerely and fervently as many worship God and Jesus and, among most Blue State Americans, more so.

He reaffirmed the position for The Atlantic in 2018, stating that “antiracism is a profoundly religious movement in everything but terminology,” and then providing an extended analysis of that claim:

The idea that whites are permanently stained by their white privilege, gaining moral absolution only by eternally attesting to it, is the third wave’s version of original sin. The idea of a someday when America will “come to terms with race” is as vaguely specified a guidepost as Judgment Day. Explorations as to whether an opinion is “problematic” are equivalent to explorations of that which may be blasphemous. The social mauling of the person with “problematic” thoughts parallels the excommunication of the heretic. What is called “virtue signaling,” then, channels the impulse that might lead a Christian to an aggressive display of her faith in Jesus….When someone attests to his white privilege with his hand up in the air, palm outward—which I have observed more than once—the resemblance to testifying in church need not surprise. Here, the agnostic or atheist American who sees fundamentalists and Mormons as quaint reveals himself as, of all things, a parishioner.

In reality, the most deeply religious individuals are the least likely to feel personally affected by the relocation of “final ends” from the public to the private sphere precisely because their membership in a rich religious community means that they have a robust fall-back to satisfy the human need for communally-affirmed meaning.

The situation is much direr among the areligious, however. Although many atheist humanists have tried in the past to replicate the communal aspects of organized religion, these artificial attempts to recreate organic social institutions have been about as successful as Esperanto.

It is secular individuals, bereft of the bolstering backstop of religious communities, who have far less recourse for anchoring their values. For this reason, I would argue, the seemingly areligious must have their “final ends” in the political sphere or they cannot experience them communally at all.

McWhorter’s analysis of anti-racism as religion deserves to be taken seriously and at face value. We’re witnessing the rise of a new religion in all but name to fill the void experienced by the growing population of Nones. According to Wikipedia,

The term “nones” is sometimes used in the U.S. to refer to those who are unaffiliated with any organized religion. This use derives from surveys of religious affiliation, in which “None” (or “None of the above”) is typically the last choice. Since this status refers to lack of organizational affiliation rather than lack of personal belief, it is a more specific concept than irreligion. A 2015 Gallup poll concluded that in the U.S. “nones” were the only “religious” group that was growing as a percentage of the population.

Unlike Protestantism and Catholicism, this new religion has no institutional memory of the painful lessons of religious wars. It therefore has no appreciation for the necessity of abiding by the terms of liberalism and keeping its own values rooted in the private sphere.

Even more importantly, the adherents of this new religion don’t see it as a religion. Without this awareness, adherents believe they are exempt from the old liberal compromises, like the separation of church and state. Their values are considered objectively true, as opposed to the subjective claims of other religions, and therefore they see no reason to accommodate themselves to the private/public compartmentalization as other religions do (grudgingly, at times). Unchecked by the constraints of liberalism and ignorant of their own nature as a religion, they have stumbled unintentionally into religious supremacy.

In short: the progressive left’s secularism led it to become acutely illiberal in a way not true of prior liberal malcontents from the left or the right.

Liberalism’s Escape Hatch

Although the secular progressive left started out on a collision course with liberalism, it still arose out of a liberal context, and that has unfortunately accelerated its animus towards liberalism.

To see why this is so, consider that all human tribes demonize their perceived enemies and do so in a way that reflects their own highest values. For a liberal society, the highest values are rationality and tolerance. Tolerance is obviously a vital value because that’s what liberalism is for. The necessity of rationality might not be as immediately obvious, but it is just as indispensable. Rationality posits truth as an objective, independently existing reality that is accessible universally (to the extent that it is accessible at all). This enables persuasion to work as a replacement for coercion. As long as both parties believe that the truth is out there, and that logic and evidence can reveal it, they both have reason to engage in dialogue with each other and with unpersuaded third parties. Take away rationality, and there is no longer any point to attempting persuasion; only coercion remains a viable strategy for contesting your opponents.

This is another reason for the illiberal turn of the progressive left, by the way. The ideological framework derives from postmodernism, which is itself inimical to liberalism because it rejects the rationality on which liberalism relies for civil discourse and non-violent political contests. Without recourse to the idea of objective truth (even if it is not fully accessible), persuasion is never more than a pretext. Thus the primary strategies of the progressive left are soft coercion and then outright physical violence. For soft coercion, see Bradley Campbell and Jason Manning’s description of how victim status is deployed as a method of “social control” in The Rise of Victimhood Culture. For outright violence, see articles like Is it OK to punch a Nazi? Which is just one example in an entire genre of progressive left opinion on the topic. The bottom line is that any ideology arising from postmodern assumptions will come to see coercion as the first and only resort.

Returning to our prior subject, the progressive left enacted the age-old, instinctual practice of demonizing their opponents by framing them as violators of the core liberal ideals of rationality and tolerance. Thus, in their eyes, anyone who disagrees is a “science denier” and a “bigot.” From this perspective, it is not possible that someone opposed to elective abortion is acting from a reasoned, principled commitment to an ideal of human equality; they just hate women. And it’s not possible that someone opposed to same-sex marriage operates from a logically-consistent, sincere idea of conjugal unions; they just hate gay people.

The tragedy of this inevitable step was that those two defects—irrationality and intolerance—are the exception clause of liberalism. Here’s Scott Alexander from Against Murderism again:

Using violence to enforce conformity to social norms has always been the historical response [when confronting irrational, intolerant opponents]. We invented liberalism to try to avoid having to do that, but you can’t [engage in liberalism] with people who refuse reason and are motivated by hatred. If you give the franchise to green pointy-fanged monsters, they’re just going to vote for the “Barbecue And Eat All Humans” party. If such people existed and made up a substantial portion of the population, liberalism becomes impossible, and we should go back to just using violence to enforce our will on the people who disagree with us. [emphasis added]

And so, precisely because the progressive left arose out of a highly liberal milieu, it chose to demonize its opponents in exactly the way that would ultimately undermine liberalism itself.

Enemies of Liberalism on the Right

The rise of illiberalism on the progressive left has been both obvious and alarming to many conservatives. I published the most widely-read piece my blog has seen, When Social Justice Isn’t About Justice, in November 2015 after over a year of research and interviewing and writing. My point here is the timing: like many other conservatives who went on to enlist in #NeverTrump, I was engaged in opposing illiberalism from the left before the 2016 primary season began and Trump threw his hat into the ring.

Two things happened with the rise of Trump, and possibly because of it. The first is that a degree of latent right illiberalism that had always been there was unmasked. In their Atlantic piece, Chua and Rubenfeld noted that:

Since the 2004 publication of Samuel P. Huntington’s Who Are We?—which argued that America’s “Anglo-Protestant” identity and culture are threatened by large-scale Hispanic immigration—there have been calls on the mainstream right to define America’s national identity in racial, ethnic, or religious terms, whether as white, European, or Judeo-Christian. According to a 2016 survey commissioned by the bipartisan Democracy Fund, 30 percent of Trump voters think European ancestry is “important” to “being American”; 56 percent of Republicans and a full 63 percent of Trump supporters said the same of being Christian. This trend runs counter to the Constitution’s foundational ideal: an America where citizens are citizens, regardless of race or religion; an America whose national identity belongs to no one tribe.

I probably should have recognized the danger of the illiberal right, but prior to the rise of Trump, I never took it seriously. I didn’t see any polls like this when I was busily fortifying against illiberalism from the left. I was blind to the illiberalism on my own side.

Although I’m certainly culpable for that mistake, I think it’s worth a few paragraphs to explain how the right’s illiberalism flew under the radars of many conservatives.

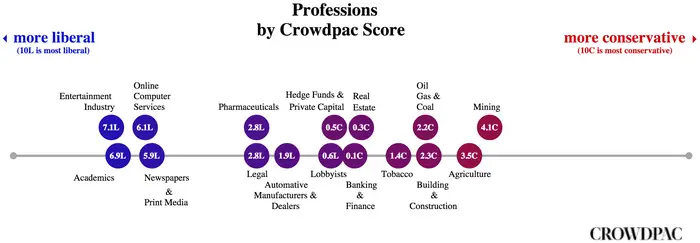

The key realization is that illiberalism is a feature not just of the left generally, but specifically the elite left. Postmodernism and its progressive scion Critical Race Theory are not blue-collar preoccupations. Although it has trickled down substantially, the origin of the left’s illiberalism has always been the Ivory Tower. From that starting point, the progressive left has managed to seize control of basically all of the socially-relevant strategic high points. Identity politics dominate not only academia, but also journalism, entertainment, and Big Tech, as one particularly vivid illustration from Business Insider reveals:

Illiberalism had made essentially no inroads among the elites of the American right prior to Trump. College-educated Republicans are less tied to their home regions, less suspicious of immigration and free trade, and more open to the benefits of globalization. They also suffer far less from the deleterious impacts of these policies, since white-collar work is less susceptible to outsourcing.

This explains why many conservatives, myself included, viewed illiberalism as an exclusively left-wing problem. Because the progressive left dominated culture (and still does), their influence was pervasive and obvious (and still is). Because the illiberal right was largely poorer, less educated, and more dispersed, I failed to take them seriously.

I also didn’t fully appreciate that, as frighteningly dominant as the progressive left had become socially, that threat never really translated into political power. As numerous polls show (here’s one from Cato), Americans today are more afraid than ever to voice their sincere opinions on controversial topics because the progressive left has the means and the motive to silence anyone who steps out of line. Cancel culture, as I’ve written, is real.

Yet despite this, the progressive left failed to make even modest headway with their policy agenda at the national level—even when they held greater political power. Forget reparations or overthrowing capitalism, the progressive left didn’t even manage to significantly move the needle on immigration policy when Democrats held the White House and the Senate and the House (2009 – 2011). It’s possible that the progressive left doesn’t even have serious policy objectives, at least not as a primary consideration. As an (unwitting) religious movement, their preoccupations seem more symbolic and philosophical than policy-oriented.

Liberalism is under threat, but the threat to liberalism from the left is a threat first and foremost to our informal institutions and cultural norms. They cancel speakers and strong-arm entire genres into compliance with “right-think,” but they have little influence among the police or armed forces.

When Trump declared his candidacy, I thought it was a joke. I was completely unprepared for him to be a viable candidate and utterly shocked when he started winning primaries. What’s more, he did it by explicitly appealing to the illiberal right. What was his number one issue? Immigration. Whether or not he was overtly racist, he was tapping into the kind of ethnocentrism Chua and Rubenfeld alluded to. If the right comes to see itself and the nation in ethnic or tribal terms, then the battle to defend liberalism is already lost. Although it won’t start right away, if the illiberal right comes to dominate conservatism as the illiberal left is dominating progressivism, all that remains is the long, downward slide into bloodletting.

Trump did more than just reveal a problem that had always been there. He galvanized the illiberal right and led them to greater heights, especially once he took office. At that point it was impossible to dismiss the illiberal right as impotent and decentralized; they were dominating the party that held the White House and Senate.

Like all aspects of liberalism, free speech has both a formal and informal aspect, and both are necessary

The backlash of the illiberal right is understandable. Because of the way the illiberal left dominates culture (through academia, journalism, and entertainment), the right was acutely aware of the extent to which progressives had effectively declared war on traditional cultures. We talk about the “culture wars” and a lot of the same issues—feminism, abortion, etc.—were involved, but cancel culture of the 2010s was virulent and aggressive in a way that political correctness of the 1990s never was, primarily because its unknowingly religious nature led it to disregard liberal safeguards (as discussed above).

It’s common to mock Christians in America for having a persecution complex, and there is truth to that. After all, the right has continued to retain (and even increase) influence over the formal institutions of power. However, the persecution complex is not a paranoid invention. It’s a reflection of the fact that conservatives in America live and breathe in a cultural context that is implacably hostile to their values. This is why conservatives are so much better at articulating progressive talking points than vice versa. (Nicholas Kristof summarized early research from Jonathan Haidt on this for the New York Times back in 2008, and Haidt went on to expand these themes in his book The Righteous Mind.) In terms of political power, conservatives are secure. In terms of cultural power, their perception as a besieged minority is real.

So this besieged minority looked at their attackers, and they did the natural thing: they emulated them.

Progressive activists are successful in large part because of their wanton disregard for liberal norms. “Canceling” is the most overt example of this. If you say the wrong thing, they will hound you out of your job and out of the public sphere entirely. Any debate about the technical, legal limits of the First Amendment misses the point here. Like all aspects of liberalism, free speech has both a formal and informal aspect, and both are necessary. We need the legal protections of free speech, but we also need an attitude that tolerates differing views. The less latitude Americans give each other to disagree without attempting to punish each other, the less free speech we have regardless of the formal status of the First Amendment.

As the progressive activists threw such informal constraints aside, they cut a swathe through popular culture, with controversies in the sci-fi community (2013), video game community (2014), comic book community (2016), and romance community (2019). In every case, their scorched-earth policies were successful, with conservatives and libertarians hounded to the margins, another formerly neutral space becoming thoroughly politicized and rigorously policed, and history (in Wikipedia and news outlets) being written so that the victors were also the righteous victims.

The success of these ventures greatly exploited the close relationships between the progressive left activists engaged in the conflict and the progressive left activists working as journalists to cover the “story.” I watched some of these controversies from a distance, but for both the sci-fi battleground and the video-game battleground I had front-row seats, including conducting interviews with lots of the participants (on both sides).

The discrepancy between the official line and the actual events was often breathtaking. Reading the Wikipedia entries for these issues and comparing them with my real-time experiences is head-spinning. The sci-fi controversy was known as “Sad Puppies” (it’s a long story) and the entry currently begins: “Sad Puppies was an unsuccessful right-wing anti-diversity voting campaign . . .” It was unsuccessful, but it was neither right-wing nor anti-diversity. The video game controversy was called GamerGate and the entry begins: “The Gamergate controversy concerned an online harassment campaign . . .” A lot of harassment did take place, but only one half of the harassment was covered in the press.

All of this means that by late 2015, there was intense simmering resentment on the American right. Some of the responses to this resentment were liberal and productive, like the launch of Quillette in that year. But a lot of the responses took a different pattern: taking the illiberal tactics that had been used against them and turning them on their enemies.

Back to Trump

It is clear in Fukuyama’s piece that he is more concerned about the illiberal right than the illiberal left. As he says:

Democracy itself is being challenged by authoritarian states like Russia and China that manipulate or dispense with free and fair elections. But the more insidious threat arises from populists within existing liberal democracies who are using the legitimacy they gain through their electoral mandates to challenge or undermine liberal institutions. Leaders like Hungary’s Viktor Orbán, India’s Narendra Modi, and Donald Trump in the United States have tried to undermine judicial independence by packing courts with political supporters, have openly broken laws, or have sought to delegitimize the press by labeling mainstream media as “enemies of the people.” They have tried to dismantle professional bureaucracies and to turn them into partisan instruments. It is no accident that Orbán puts himself forward as a proponent of “illiberal democracy.”

I know it’s been a long road, but all the pieces are now in place to explain why I, and other #NeverTrumpers, agree with Fukuyama’s assessment that the illiberal right—including Donald Trump—is the greater threat.

The only saving grace of the monstrous, illiberal progressive left so far has been its inability to seize control of government. It is bad enough to have “cancel culture” when a mob of private citizens cruelly hounds another private citizen out of a job, out of public life, or maybe into suicide. How much would it be for a similar mob to have the backing of the police, the federal bureaucracy, and the courts?

This is what everyone on the liberal right asked themselves when they saw Donald Trump leading chants of “Lock her up!” in 2016. There is nothing more antithetical to liberalism than the idea of using formal state power to punish political opponents. Obviously, this has occurred before in the past, but not openly and to great applause. We were shocked and horrified by the way so many Republican voters ate up fear-mongering, anti-immigrant rhetoric that repudiated the liberal legacy and aspirations of our country by conceiving “Americanness” in ethnic rather than philosophical terms. After years of gearing up to fight a seemingly losing battle against the illiberal left, we woke up one day to find out that the enemy was already within the gates.

We foresaw the worst excesses of the illiberal progressive left replicated by the illiberal reactionary right which actually would have control of our government. Smug, hypocritical Hollywood scolds are nauseating, but their real power is limited. The prospect of Steve Bannon leading an illiberal policy apparatus from the White House constituted a far, far greater long-term threat.

What does this mean in concrete terms?

Well, I have to admit that Trump’s first presidency is not as bad as I and many #NeverTrump conservatives feared. He is not an ideologically committed illiberal as those on the left are. This is because he has no discernible ideology whatsoever. His illiberal tendencies are the result of a bottomless thirst for popularity wedded with a total disregard for the norms and rules of government that is born of ignorant recklessness rather than philosophical opposition.

Left to his own devices, Trump would long since have trampled every liberal norm into the dirt and the Constitution along with it, but he hasn’t been left to his own devices. He has been stymied again and again by adults in the room who prevent him from doing most of the outrageous and frequently illegal things he has tried to do. (As I write this, rumors abound that he is about to fire yet more Justice Department officials for being insufficiently willing to manipulate the levers of the executive branch to Trump’s personal political ends.)

In addition to these considerations, it must be admitted by any honest conservative that Trump has implemented many important conservative policies, especially in his appointments to the Supreme Court. The case against Trump, from a liberal standpoint, is neither trivial nor open-and-shut.

The real danger I see is not from Trump himself but from the failure to repudiate his actions. Trump is no political mastermind or committed ideologue. What happens if, a presidency or two from now, we get someone who is?

In a world where Trump’s disregard for rule of law and norms of liberal civility has been left to stand without correction, it would be far too easy for a real authoritarian—from the right or from the left—to use these bad precedents and the public’s cynical disregard as a runway for a much more competent, focused attack on American liberalism. That’s how precedent works. Trump has vastly expanded the range of options for all of his successors, and therein lies the long-term danger.

In 2016, Michael Anton wrote a piece in the Claremont Review of Books depicting the choice between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump as the “Flight 93 election,” referring to the doomed United Airlines Flight 93 that crashed in Pennsylvania on September 11 when the passengers attempted to retake it from the hijackers. In it, he excoriated conservatives who were reluctant to vote for Trump, insisting Trump was necessary to combat the “ceaseless importation of Third World foreigners,” and calling for “no more importing poverty, crime, and alien cultures.” He later turned the essay into a book in which, according to Wikipedia, he argued that Trump provided “the first serious national-political defense of the Constitution in a generation.”

So, according to Anton, defending the Constitution means defending America from the wrong ethnicities. This is the opposite of what the Constitution, as an embodiment of liberalism, stands for. This is how Trump and his supporters constitute a battle for the soul of the American right. If Trumpism wins, America will cease to have a partisan defender of her real, essential nature as the world’s first and greatest liberal project.

I do not wish to replicate Anton and replace one flight 93 election with another one. It is not the case that, should Trump win in 2020 again, our liberal order must necessarily collapse. Far from it, I do not believe Trump has the capacity to bring that end. But there is a struggle going on for the soul of America, and it’s not clear how much more strain our society can take before we pass some point of no return where liberalism begins to give way to fracturing (secession) and violence (civil war).

Moreover, this election is the one, last chance Americans have to repudiate Trump’s bad precedents. To try and pick a different path. That’s why the #NeverTrump conservatives have such an important role to play, even though our numbers are small. It’s important not only for Trump to be defeated but for his defeat to represent a rejection of his disregard for our liberal heritage.

Even though this election is not the all-or-nothing decision point, America really does face two possible futures. In one, an illiberal left and an illiberal right engage in an endlessly escalating confrontation that no one can possibly win. Whoever winds up on top of the heap will no longer govern a country worth having, because it will not be the United States of America founded in the liberal proposition that “all men are created equal” and consecrated to the ideals of liberty, diversity, and tolerance through limited government and rule of law.

In the other, a liberal center coalition of Republicans and Democrats beat their respective fringes back into submission and resume conflict within the confines of liberalism. I sure hope the right wins this contest more than it loses it, but even when my side is the losing side, at least at the end of the day I’ll still live in a country that aspires to be a city on a hill.

Which brings me back to where I started: this is deeper than policy. I would rather live in a liberal nation with policies I hate than an illiberal one where an authoritarian strongman imposes policies I happen to agree with.

Trump is not as bad as many have painted him to be. His ideological aimlessness and fear of unpopularity disqualify him as a proto-dictator. He is callous and opportunistic in his ethnocentric appeals, but not an overt racist. Many of his policies and decisions have been good. But a lot of them have been awful, like separating families at the border. And he is a bad person: dishonest, disloyal, and intemperate. But beyond and beneath this all is the fact that Trump rose as the figurehead of the illiberal right. He was the one that the illiberal right turned to when they decided to use the illiberal left’s tactics against it. He is the avatar of right illiberalism, and to save our liberal heritage he must be repudiated.

I understand the temptation of Christians who see that we seem to be losing a cultural battle against a new, insurgent religion that discards the constraints and legacy of liberalism, but we cannot afford to retaliate in kind. Doing so would cost us our soul. For Latter-day Saints in particular the reasons not to give in to the temptation to hit back are strong. Not only do we have a scriptural commitment to the Constitution and the guidance of leaders who connect that to liberalism, but we also have a theological commitment to eschew coercion as we seek to build Zion. Liberalism is not Zion, but the tolerance and non-coercive regime it protects is an essential incubator in which we can, through persuasion and volunteerism, build that perfect community.