Over the years, there have been significant changes in the American election process. These range from how we vote, such as the rising popularity of early voting, to even who is able to vote. However, one of the biggest yet undiscussed changes is how, historically, we used to vote for candidates of different political positions.

Before the 17th Amendment was ratified in 1913, it was the legislatures from each state that chose who would represent the state on the federal stage. This method was designed to strengthen the federalist ideals of those attending the Constitutional Convention. However, because of this amendment, it will be you voting for your senator on November 5.

The argument for this change was to increase the power of the voter by allowing them to directly affect who would be the federal spokesperson for their state. Paradoxically, the unforeseen consequences of this action have led to a loss of freedom for individuals in any particular state. The focus and incentives for a senator shifted from protecting the state’s autonomy to focusing on the next election cycle.

This resulted in what is referred to today as dual federalism. Instead of the federal and state governments operating in two different spheres, they are now combined in fundamental ways. Instead of fighting to keep the federal government out of their turf, senators are now fighting to allow the government to enact laws in their states called “federal mandates” so they can receive more funding from the federal government.

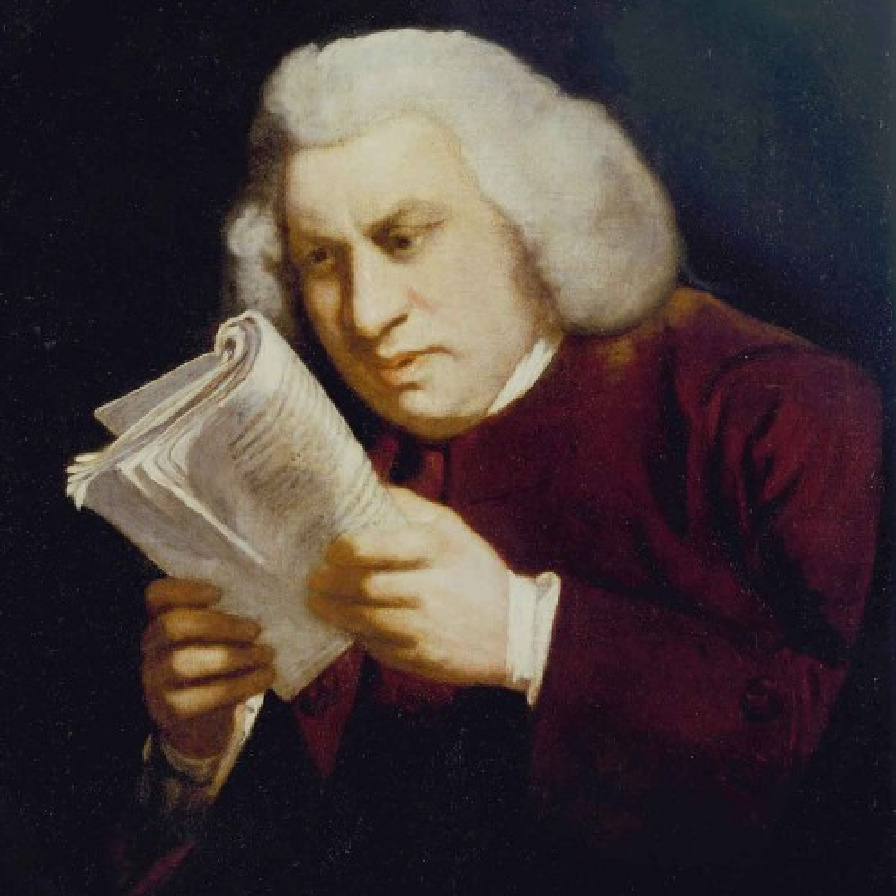

This compromising relationship between the state and federal governments has seemingly led to the squandering of the rights of the average citizen so the state can make a quick buck—all done under the guise of increasing democracy. The checks and balances of the legislative process were carefully considered by wise men.

The Senate is not the only office affected by America’s shift from a constitutional republic to the vicious wolves of a pure democracy. Even the high office of the president is being influenced by this cultural shift.

What is the purpose of the President of the United States? I don’t believe either candidate would have the correct response to that question. Donald Trump would probably start talking about Haitian migrants eating cats and dogs, while Harris might monologue about being raised in a middle-class family in Canada. Both candidates would probably answer as they have before, explaining their different policies.

But that’s not the role of the president. Perhaps someone with a strong understanding of the Constitution will point to Article II broadly and say, “Here, this is the role of the president.” Even so, I think we need to be more specific than that. Although Article II enumerates the executive powers of the president, one line explains the role of the current president: the Oath of Office.

As the U.S. Constitution, Article II, Section 1 states, it is the president’s duty to “preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States” to the best of their ability. And as George Washington so beautifully put it, “So help [them] God” if they don’t.

If that’s the role of the president, then shouldn’t that be the standard by which we elect them? Maybe when voting for the POTUS, we shouldn’t be asking ourselves what their views are on taxes, transgender athletes in women’s sports, climate change, or IVF. Instead, we should ask ourselves who would do the best job of preserving, protecting, and defending the Constitution as it is written.

That’s not to say that these issues aren’t important. They are. Both sides of these debates need to be discussed and considered at the federal level. However, that is the role of the House of Representatives—to discuss and promote what you, the person they represent, feel about any one of these issues. For this reason, the Electoral College was conceived. Its goal was to prevent the office of president from being one of pure populism.

The checks and balances of the legislative process were carefully considered by wise men. The goal of the Constitution in this aspect was to involve the consent of every involved party before anything could become law. First, a bill must be proposed by either the House or the Senate and approved by the other. The passing of a bill in the House will signify the will of the majority of current citizens of the United States. The Senate will then convey the concurrence of the majority of states on the same matter before the bill can be moved from Capitol Hill to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue.

Then the president will read through the bill. Before signing it into law, it is their duty to determine if it aligns with the wisdom of the ages as portrayed in the Constitution. No matter how important, prudent, or popular a bill may be, it is the sacred obligation of a president to veto that bill if it does not align with the Constitution. If that bill is truly important and widely accepted enough, then there should be a national consensus to support an amendment that would allow for such a bill.

This election, I would encourage you to try to adopt this perspective. Don’t treat your senator like a representative. Vote for a senator who will stand up for the rights of your state. Conversely, when voting for the president, ask yourselves: Who do I trust to preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States of America?