President Monson liked to say, “Life by the yard is hard; by the inch, it’s a cinch.” Well, then how difficult is it by the mile or parsec? I love the eternal perspective advanced by the Church of Jesus Christ, but when it comes to dating and marriage it can feel like more than we can handle sometimes. For some, it’s already a lot of pressure to imagine an entire life with someone, but then we layer on “all eternity” after that. Especially when a person with same-sex attraction or who identifies as gay, lesbian, or bisexual has concerns about his or her ability to be a fulfilled and faithful spouse, the added pressure of an eternal future together can feel unbearable. Under that pressure, even under the best of circumstances, it can be difficult for the delicate flower of attraction and deeper intimacy to develop.

People with a number of identities and persistent feelings around sexuality can experience this concern—including those who experience same-sex attraction, and those who identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual. What I’m about to say also applies equally well to those who are identifying in greater numbers as polyamorous and/or pansexual. For convenience sake, for the rest of this article, I will refer to all of these individuals as sexual minorities.

In the Church, two historical strains of thought are currently influencing the question of heterosexual marriage for sexual minorities, and both of them work against the chances of formation and success of these marriages.

Marriage as a cure. The older strain is the folk belief, sometimes still espoused by members and leaders, that heterosexual marriage will fix, or resolve homosexual attractions. By (a) “doing what comes naturally” and given time and care, the encouragement goes, whatever nervousness or awkwardness or lack of skill or enjoyment is initially present in intimacy will soon give way to a deep and abiding sexual and emotional fulfillment, and then (b) any same-sex desires or temptations will fade and eventually disappear altogether in the solvent of wedded bliss.

While part A of this formula is reassuring advice for the typical jittery heterosexual virgin on his or her wedding night—these kinds of things can and do grow over time for most any couple— the overall formula represents terribly insufficient advice for sexual minorities preparing for marriage. Some took this advice without disclosing their sexuality to their spouse (after all, why bother if it’s just going to go away soon?) and were eventually disappointed. Shame piled upon secrecy, and all too often the marriage ended with not only the couple heartbroken but children as well. Some sexual minorities within these marriages found that while they could perform sexually with their spouse, there was still a void, a yearning, for a same-sex relationship that included sex and romance. No amount of sex within the marriage, no matter how frequent or enjoyable, entirely eliminated that yearning.

Others were not able to do even that much, either avoiding all sexual contact except on rare occasions or having fantasized that they were with a same-sex partner in order to function sexually. Such marriages might last, but they were far from satisfying for either partner. The heterosexual spouse, in particular, felt deceived and betrayed. Heartache and disappointment for both partners were frequent in at least some of these “this will fix me” marriages.

The pendulum swings too far the other way. This prompted President Gordon B. Hinckley, then First Counselor in the First Presidency, to say in 1987, “Marriage should not be viewed as a therapeutic step to solve problems such as homosexual inclinations or practices.” This statement, however, led to the development of the newer strain of thought within the Church. This position cautions that any sexual minority, and definitely no one who identifies as gay, should ever marry heterosexually—with any such marriage seen as inauthentic for the sexual minority and unfair to the spouse. From this line of thought, no one who does so is being “true to oneself” and anyone who attempts this is engaged in a pathetic sort of playacting. (This is somewhat ironic because this is how many first- and second-wave gay rights activists viewed same-sex marriage, as a sort of play-acting on the part of gays who were dealing with internalized homophobia and felt a more conformist lifestyle would increase acceptance of their minority sexual behavior.)

As more and more people have been acknowledging, the idea of marriage as a therapeutic vehicle for personal self-actualization is a relatively new idea and a highly damaging one. By many measures, this noxious (and seductive) notion has led to countless broken homes and two generations of children of those divorces suffering subsequent harms, both small and large. I would go further than President Hinckley. I would say that marriage should never be undertaken by anyone as a therapeutic step to solve any sort of problem. Individuals should take responsibility for their psychological issues rather than expecting their partner (or children) to “fix” or change them. Marriage itself is a powerful and amazing form of therapy, but those therapeutic effects happen when both partners take full responsibility for their own growth and healing and share an ironclad commitment to each other.

Returning specifically to the idea that sexual minorities should not consider heterosexual marriage, this strain of thought is also an overreaction, and it can be seen by viewing President Hinckley’s comments within their full context:

The Lord has proclaimed that marriage between a man and a woman is ordained of God and is intended to be an eternal relationship bonded by trust and fidelity. Latter-day Saints, of all people, should marry with this sacred objective in mind. Marriage should not be viewed as a therapeutic step to solve problems such as homosexual inclinations or practices, which first should clearly be overcome with a firm and fixed determination never to slip to such practices again.

Lest that final bolded phrase spark an explosion, let’s clarify what exactly President Hinckley is saying—and not saying—there.

Hearing President Hinckley clearly. As I will discuss in a follow-up article, there are a number of factors that increase the chances that these marriages can thrive. One of the most important ones is the history of past behaviors. Whether these are substance addictions or sexual behaviors that have the potential of inducing betrayal trauma in the spouse, the spouse has a right to know beforehand the scale of these past behaviors, because while we believe in change and repentance, what has happened before can happen again. While there are no guarantees in marriage, the spouse should have enough information and history to feel confident that serious behaviors are in the distant past and any recurring ones are manageable.

The Latin proverb “falsus in uno, falsus in omnibus” also applies here; small evasions or lies about significant matters are a red flag. Therefore, the most important element is a willingness to be completely and promptly honest, because when the earlier issues are disclosed the less likely they are to snowball to truly tragic ones. During the courtship process, if a culture of openness and willingness to discuss difficult topics even when painful can be established, this will bear tremendous fruit across a wide variety of areas in the ensuing marriage.

When President Hinckley says “inclinations” should “clearly be overcome,” I do not think he is espousing some sort of conversion therapy. He’s not saying the person should no longer experience any attraction to the same sex anymore, since reduction/elimination of homosexual feelings is neither necessary nor sufficient for a successful marriage to the opposite sex, even though significant shifts in homosexual attraction spontaneously occur much more commonly than many suppose.

Instead, I think he is referring to the persistent and debilitating yearning that many sexual minorities have for a romantic and sexual relationship with the same sex. Quite a few sexual minorities will tell you that the strictly sexual temptations to lust and other behaviors can be quite manageable, especially as they get older. They may be temporarily distracting and intense, but they pass within hours or days. It’s this chronic emotional longing for a romantic and sexual relationship outside of a current (or theoretical) heterosexual relationship that is for them much more difficult to handle over time. In my experience, the inability to quell this yearning, and the resultant depression and anxiety, is what leads to divorce (or not marrying in the first place) far more often than extramarital sexual behavior per se does. Marriage should never be undertaken by anyone as a therapeutic step to solve any sort of problem.

Read carefully, President Hinckley is not counseling against heterosexual marriage for sexual minorities. In fact, his conditions for entering marriage are excellent advice for anyone attempting marriage. You will note that nowhere in there does President Hinckley say that marriage is a vehicle for personal fulfillment or self-actualization. He, and other Church leaders, have a totally different view of marriage than we see in popular media. While romantic love and sexual expression certainly have a role, President Hinckley speaks of “trust” and “fidelity.”

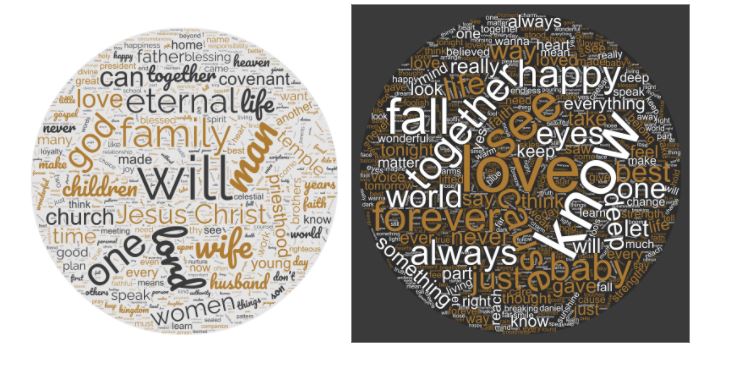

Two very different love conversations. While not a very rigorous method, I like word clouds to show how prominent certain words (and the concepts and worldviews that underlay them) show up in texts. They are an aesthetic way to illustrate word frequencies. I built two word clouds using an online word cloud generator. The first word cloud is composed of the top ten most helpful general conference talks about marriage given recently as compiled in this list. I removed words like marry, marriage, married, because that was the topic of the talks. I also combined plural words like brethren/brother.

Next, I compiled all the words in ten popular secular wedding songs as compiled by a popular wedding magazine. I did not remove any references to marriage in this word cloud (as there were hardly any anyway). Here are the results of both exercises:

Viewed side-by-side, the contrast is striking. The only reference to anything transcendent or long-lasting are the words “love” and “forever” (including, arguably, “always”). Any references to family or children are wholly absent. (The “baby” here is not referring to an actual infant, but the term of endearment for one’s romantic partner.) There are no references to religious, moral, or ethical principles, and it is fair to say that the “love” that is so prominently mentioned refers to the feelings around romantic love, rather than the ideal of Christlike, sacrificial love.

But it really is the latter kind of love which Jesus calls us to, rather than the personal romantic ecstasy worldly voices encourage us to crave today. As Ty Mansfield recently pointed out, Jesus did not say “Greater love hath no man or woman than this, that any and all consenting adults should experience passionate romance, intimate pair-bonding and maximized sexual fulfillment all the days of their life—and, be wary of children, for they may inhibit life satisfaction.” (Though that is a fair summary of the way these songs see love and the marital relationship).

Comparing the two word clouds, what stands out to me is that the first word cloud is focused more on the eternal and transcendent, and has an action-oriented view. The second one seems to be more passive, more about what one feels—especially in the immediate moment. The only overlap I can discern is the related concepts of “eternal” and “forever.” (A fun rock n’ roll-gospel connection that Loren Marks and David Dollahite explored two years ago around Valentine’s). This represents a yearning for lasting love, but nothing else in the cloud provides any tools to ensure that the marriage can even endure a lifetime, let alone encourage the covenant-making and keeping required to harness the sealing power which, alone, ensures that these relationships endure beyond death.

Real-life consequences of competing narratives of love. So why does any of this matter? Well, it turns out the ideas and words and language we choose to emphasize, even unaware, all have enormous implications for the practical details of our lives, and the directions we end up going. In this case, anyone holding to this more recent, self-centered, therapeutic ideal of marriage has little reason to enter into a traditional marriage, and even less so for a sexual minority to do so with the opposite sex.

From this vantage point, traditional marriage commitments are too limiting, too likely to impair life satisfaction and happiness. And since that is some people’s highest goal, traditional, committed marriage is just going to get in the way of that. This is why when a sexual minority person marries traditionally, it is seen as something inauthentic, abnormal, freakish, and almost certainly doomed to fail. And so these marriages become subjects of public discussion, as with Ty and Danielle Mansfield, Josh and Lolly Weed (now divorced), mine and my friends’ marriages, Skyler and Amanda Sorensen, and most recently, Nicholas and Jordan Applegate. In recent years, some skewed-sample research has been weaponized to cause some people to incorrectly believe that these marriages are miserable, with higher-than-average divorces, and more physically harmful than lupus.

The popularity of these opinions combined with the veneer of scientific respectability adds heat and light to the sometimes overwhelming pressure I described above. With that kind of deck stacked against them, it sometimes seems like it would be a miracle if any of these marriages survived. And here is the paradox: many, many marriages like these do! Great heat and pressure under the right conditions are what transform ordinary, worthless charcoal into beautiful and precious diamonds. After diamonds are forged in this crucible, they are among the strongest substances known to man, and they reflect light brilliantly.

Proposing a new name. So far, I have carefully avoided the term “mixed-orientation marriage.” You might have noticed. That’s because I hate this term. It’s certainly a widely-accepted scientific term, but I dislike it because it seems to validate this idea that marriages like mine are unusual, freakish, and exotic—worthy perhaps of gawking at during a trip to the zoo, but rarely encountered in the wild. They are a scientific curiosity but largely irrelevant to daily life. As I will show in a moment, they are not that unusual. Contrary to popular rhetoric, there is evidence that more sexual minority people are heterosexually coupled than are in same-sex relationships, and if anything, they are becoming more common.

Some will lament this fact—wringing their hands about an expanding array of people destined to be unfulfilled. But that is as short-sighted as the rest of the conversation about “mixed-orientation marriages.” Certainly, all marriages face challenges and real threats to happiness, and these marriages are no exception. But the dire and dark estimates miss the profound happiness that most such marriages find—despite these enormous added forces of opposition designed to thwart them at every stage. When a sexual minority person marries traditionally, it is seen as something inauthentic, abnormal, freakish, and almost certainly doomed to fail.

The relative frequency of marital types. How can I possibly claim that sexual minorities are more likely to be in heterosexual relationships? The best survey ever conducted on sexual behavior was the National Opinion Research Council (NORC) study conducted by Edward Laumann and colleagues in the eighties. While not highlighted in the findings, when you look at the numbers, it showed that most of the men who experienced some degree of homosexual attraction had never had homosexual sex. It also found that more of them did not identify as gay than did, and more of them were in heterosexual relationships than were in homosexual relationships.

These numbers are clearly older—have they changed since the acceptance of same-sex relationships is much greater now than in the eighties? Unfortunately, a study as exhaustive and well-sampled as the NORC study has not been repeated in the United States since then, but we do have some suggestive Gallup polling data. Since 2015, just before the Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage nationwide in Obergefell v. Hodges, Gallup has been surveying LGBT Americans about their relationship status annually. Two articles, one published in 2017, and another follow-up published last year by Gallup, show some interesting trends in polling.

Gallup’s survey data say that the share of LGBT individuals who are single has actually increased since gay marriage was legalized nationwide. (Slightly more are married since it’s become available nationwide, but that is compensated for by an even greater decrease of those unmarried but living together.) The share of single, never-married LGBT-identifying individuals has gone up about six points since before Obergefell. The percentage of LGBT individuals in opposite-sex relationships in 2021 was 20.6% and the percentage in same-sex relationships was about four points lower at 16.7% in that same year. This latter number has gone down four percent since 2015 (before nationwide gay marriage), while the share of LGBT individuals in opposite-sex relationships has gone up by almost two points. (The total number of people identifying as LGBT has grown over these years, so it’s important to note that these are relative numbers; absolute numbers in all of these categories have increased.)

So we have an interesting picture. More and more people are identifying as LGBT (the omission of Q+ is deliberate; the survey does not have a sampling size sufficient to say anything definitive about these other identities yet so rather than adding these characters as is dictated by current style guidelines, I have kept the older formulation for precision’s sake). But among that increased number, fewer are in same-sex partnerships than before—about 4% more of the pie are in heterosexual relationships and the balance are now in the never-married/single slice of the LGBT relationship status pie.

To be sure, most of the LGBT individuals in opposite-sex marriages identify as bisexual rather than gay, but this percentage no doubt also significantly undercounts diamond marriages, because there are a lot of people, like me, who experience same-sex attraction and who are traditionally married yet do not identify as gay or bisexual. People like me would not even be counted in Gallup’s survey. The pollster would call me, ask me if I identified as LGBT, I would say no, and the pollster would hang up and call someone else.

Yes, but aren’t these marriages unhealthy? To assess the health of these marriages, some researchers across the ideological divide followed up on the earlier, flawed study I mentioned above by recruiting a broader and larger sample population. This survey asked respondents about their relationships and satisfaction. Known as the Four Options Survey, the results showed that 80% of the respondents in opposite-sex relationships described themselves as satisfied with their relationship. The survey also showed that diamond marriages had an average duration several years longer than same-sex relationships. (A helpful review article on gay, lesbian, and bisexual relationship stability can be found here. An interesting claim you will hear repeated is that bisexuals have a better prognosis for a successful heterosexual marriage than gay-identified individuals, but according to this review article, the research doesn’t seem to bear this out.)

We can’t take this Gallup survey data too far, and though the Four Options Survey’s subject recruitment was broader than the original survey, it is still also a convenience sampling. I wish we had better-sampled data with follow-ups with the same people over time to see how sexuality and relationships evolve and mature over time, and how they compare to both exclusively heterosexual couples and same-sex couples. But what I have shared here should be more than sufficient to demolish the wearisome canard that diamond marriages are (a) rare, (b) almost always unhealthy, and (c) won’t last.

February is a time to focus on relationships, so it’s a good time to ask questions when it comes to these relationships. First, can people who are part of a sexual minority develop a sufficient attraction to the opposite sex? Secondly, what factors can best ensure a successful and happy marriage, if a sexual minority person decides to undertake such a marriage?

I will be taking these up in a follow-up article. For now, a final word about those who may not be able to be married.

Unnecessary burdens & incredible solace. Despite all the foregoing suggestions, for some people, marriage may not be in the cards. Sometimes, people make their best efforts, exercise faith, and yet still the opportunity and capacity for marriage may not present itself. For these, I have a suggestion and an observation that together will hopefully provide some relief and comfort.

The suggestion: I started this essay with a quote from President Monson. I think saying “I will never get married” makes things unnecessarily heavy and bleak—this is “hard by the yard” thinking. This may be a protective, natural reaction to the disappointment and heartache that comes with a failed relationship. But we then can compound that pain by adding an unnecessary “never again” to it.

Consider, instead, what it would feel like to try embracing the tensions within a seeming paradox. On one hand, recognize that your hope is fragile, acknowledge your pain and disappointment, and accept that marriage may never happen for you in this life. That acceptance is important, but the other half of the paradox is too: don’t surrender to the despair of never. You may just end up being surprised at what is possible! In this way, foster a very healthy uncertainty and openness to the future. This is a tough balance, but to my mind, it is the correct balance to strike. None of us know what the future holds. We take one day at a time, each day as it comes, challenging the tendency to project our current situation infinitely into the future.

My uncle married for the first time in his sixties. My belief over many years that I would never get married and never have a successful relationship significantly added to my already heavy burdens, adding an unnecessary weight of despair and depression. Being single and dating can already be difficult for any of us, without adding this additional, avoidable burden.

The observation: Some of the most extravagant promises the Lord makes, in some of the most beautiful language in holy scripture, are to the single and childless who remain faithful to Him. To them, the Lord says if they “take hold of my covenant,” He will “give in mine house and within my walls a place and a name better than of sons and of daughters: I will give them an everlasting name, that shall not be cut off.”

Did you hear that? In the Old Testament (and most cultures except our own), about the worst thing to happen to someone was to be deprived of offspring—and here the Lord is promising these people something better than having sons and daughters. Rather than some afterthought, the Lord assures them they do have a place “within His walls.”

He continues, “Even them will I bring to my holy mountain, and make them joyful in my house of prayer … their sacrifices shall be accepted upon mine altar; for mine house shall be called an house of prayer for all people.” It can sometimes be painful to be single in a church like the Church of Jesus Christ, which puts such emphasis on family that you may feel like an outsider or forgotten. But the Lord boasts that He is one who “gathereth the outcasts” and that they are not forgotten, but given an “everlasting name, that shall not be cut off.”

A couple of chapters earlier the Lord speaks to those without offspring. The Lord tells them not to be ashamed, that “more are the children of the desolate than the married wife,” and promises that the Lord shall join with the entire Church in a wedding feast of the Lamb. Christ is the Bridegroom, and we, the entire Church, are His joyful bride whom He promises to join with in eternal union. No mortal spouse can surpass this beauty, or compare with this magnificent promise.

Here and elsewhere, the Lord calls out to the “afflicted, tossed with tempest, and not comforted.” And speaking of precious gemstones, the Lord promises to the childless (and I would add, unmarried) that He “will lay thy stones with fair colors, and lay thy foundations with sapphires. And I will make thy windows of agates, and thy gates of carbuncles, and all thy borders of pleasant stones. And all thy children shall be taught of the LORD; and great shall be the peace of thy children.”

In dark times, these promises may seem difficult to believe. I don’t blame anyone who decides that this invitation is too difficult to even consider (believe me, I get it!)—although I’ll likely still mourn what knowledge and blessings I believe you are giving up by doing so.

These “sapphire singles” who “take hold of [His] covenant” are granted perhaps the greatest promises of all. Far from second class, the Lord says to those who keep their covenants, “the mountains shall depart, and the hills be removed; but my kindness shall not depart from thee, neither shall the covenant of my peace be removed, saith the Lord that hath mercy on thee. … This is the heritage of the servants of the Lord, and their righteousness is of me.”

I believe these promises apply doubly for those sexual minority sapphire singles who remain open to the possibility of heterosexual marriage, who are dating or who are open to dating the opposite sex, despite the many difficulties and worldly scoffing that frequently ensues.

Sapphire singles and diamond marriages might be dismissed or disdained by the world. But for those with eyes to see, the promises are great and the blessings are rich. I testify that the Lord’s promises are sure, that as we learn to rely on Him a richer and deeper relationship than any earthly one will develop, and that it will become one of our most cherished gifts, “more precious than rubies.”