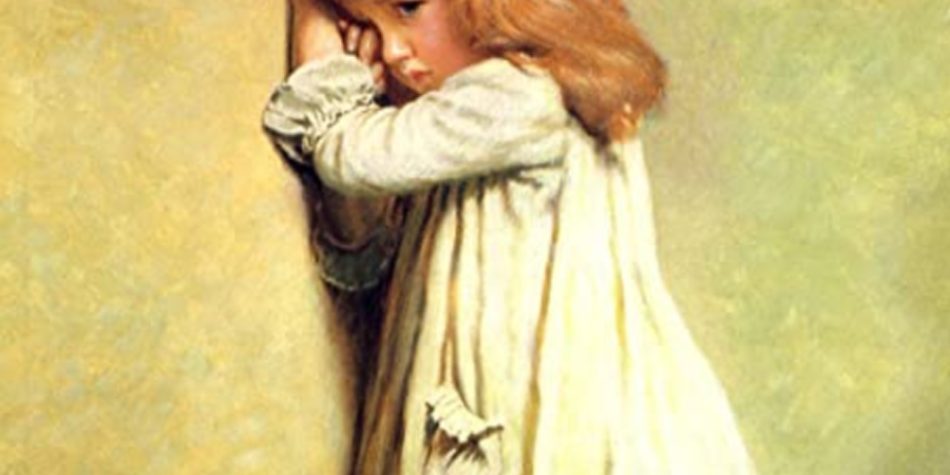

As a young child, I would often feel warm and happy singing with everyone else in church. But when I sang lines like “with parents kind and dear” and “There is beauty all around when there’s love at home,” something felt confusing and heavy in my heart. Singing those words didn’t feel the same because of what was happening at home.

I am a survivor of many years of childhood sexual abuse. When something despicable happens to any child, it’s beyond confusing; it exceeds what a child is capable of comprehending. What I experienced was so traumatizing my mind blocked the most horrific abuses from memory. It was only years later, working with trained trauma specialists, that the extent of abuses became clearer, and I began to explore the cause of frequent night terrors, which prompted new questions regarding once vague childhood memories. I was not prepared for what I learned. For over a decade—not just the few times suspected—I suffered many sexual traumas and other abuses from people both inside my family and in the area where we lived. Yet except for those involved, no one—not even my parents—were aware of all that was taking place.

The discrepancy between how my family presented themselves at church and what was actually happening at home was dramatic. I remember receiving an award with my siblings for being the most well-behaved and reverent children in Primary. But I knew I hadn’t been sitting quietly because I was “thinking of Father above.” Instead, I was just doing my best to hold still to avoid a knuckle rap to the head for wiggling.

When I was disciplined, it was rare for Dad to question accusations against me; punishments were often swift and painful, yet I was nearly always innocent. When I did err, it was due to normal developmental learning mistakes. I was never purposefully disobedient; I wanted to be good, but I feared his anger if I was not. “Do what you are told” (with an implied “Or Else!”) was drilled into my head so well that when a teen from down the street warned, “Now, don’t tell anyone, or you know you will be punished like before,” I froze in fear. I believed him.

How could our family present so well at church while so many dark secrets remained hidden? Why is it that there can be such a sharp discrepancy between public and private behavior, leading those around to miss what’s actually going on in individual homes?

Part of that painful question can only be answered in the hearts of perpetrators, many of whom have likewise endured traumas. I’m confident another part can be answered by improving system limitations—the focus of much public discussion these days. But there’s another significant answer to the question that we’re not saying much about right now, that is critical to explain and perhaps better understand why abuses continued so long in my family and in so many others.

Namely: it is extraordinarily difficult for others to know when sexual abuse is happening. I know—because even when surrounded by kind members of the Church, they did not—and in many cases, simply could not—know about what I was experiencing at home. While some occasionally picked up on my dad’s anger issues, that was it! Unlike physical abuse, sexual abuse doesn’t leave any identifiable markings on the body that might alert others. And considering the tendency of many believers to assume the best and focus on the positive, religious communities haven’t always had enough awareness regarding these painful possibilities (and realities). Because of this, it doesn’t surprise me that leaders and members who interact with victims perhaps only once or twice a week are sadly so likely to miss the signs that do exist.

We can all do a better job keeping our eyes open for them. In addition to parental anger issues, those signs include children who are extremely well-behaved or who exhibit high anxiety or depression, avoiding eye contact, poor social skills, and flinching when adults come too close. Incontinence issues and frequent UTIs at a young age are also signs. Evidence of bullying that goes beyond normal sibling arguments and inappropriate remarks or jokes about developing bodies within families should also be taken seriously.

These and other clues were evident in my family, but they were missed. That is heartbreaking, but it’s a painful reality for many families who experience ongoing abuse—including perhaps the recent case of the girls in Arizona. The more I read about it, lack of awareness seems central to what actually took place there—especially when you examine the court documents. And yet the difficulty of seeing these signs did not show up in the extensive report appearing about the case. Not once did I read or hear it mentioned how easy it can be to miss clues that sexual abuse is happening in a home.

And as a friend recently pointed out to me: “this difficulty is common knowledge among those studying abuse, with reviews of available statistics confirming that the “vast majority of child sexual abuse incidents are never reported to authorities.” As one research team recently noted, since child sexual abuse is “highly stigmatized, and blame can be placed on the victim, rather than the perpetrator,” there is a risk without “adequate safeguards” that “disclosure can potentially put participants at risk of retaliation, social exclusion and without access to their basic needs, if the perpetrator is someone they are dependent upon.”

I know many have welcomed recent reports on the subject as something that can help us move forward in improving our current accountability system. But even with my own similar experiences, I can’t help but feel the opposite is actually true. I worry that the way reporting and commentaries are unfolding, they are far more likely to set us back.

Why? Because abuse situations of any kind—especially sexual abuse cases—require great sensitivity and discernment—all of which become more difficult in an atmosphere of fear and anger. That kind of charged public conversation can drive any of us to oversimplified conclusions without sufficient attention and consideration of the many factors involved. Because circumstances are so unique and individual, we need more wisdom and discernment—not swift reactions to establish more blanket rules.

I’m in my 60s, and I still fear exposing painful family secrets, but I feel compelled to offer my perspective because of the specific and narrow conclusions being reached in this important conversation today. I believe vulnerable children would be better protected if we recognized the complexity of sexual abuse situations and the great variability of each and every case.

Without that kind of wisdom and discernment, we may too easily fall into imbalanced tendencies with heart-rending outcomes. For instance, I’ve observed extreme overreactions to curious children engaged in one-time sexual experimentation—which prompted immediate reporting to authorities, and one of the children was labeled “a child molester” until reaching adulthood. While what happened was obviously wrong, I believe this could have been handled in a more sensitive and compassionate manner. In the opposite direction, one of my abusers made a limited disclosure regarding the actions of a sexually abusive babysitter that were not taken seriously enough. As a result, this person acted out on me the traumas he experienced and then continued to sexually assault me for many years.

It is possible to overdo reaction and accountability, just as we can tragically underdo it. And in especially complex situations, such as the Arizona case, we need to encourage and support those tasked with the very difficult decisions of navigating what to do and how to help—not weigh them down with heavy accusations.

With all the acclaim a particular AP journalist has received, I don’t believe he’s aware of the damage he is causing. Rather than invite greater sensitivity and attention to the difficult task of supporting families, his words have unleashed a kind of lynch-mob mentality against the Church as a whole, connected directly to the misrepresented story he tells about what happened.

Maybe the greatest negative consequence that could emerge from this kind of accusing public discourse on abuse would be to push away those suffering the effects of child sexual abuse from the one ultimate and true source of healing.

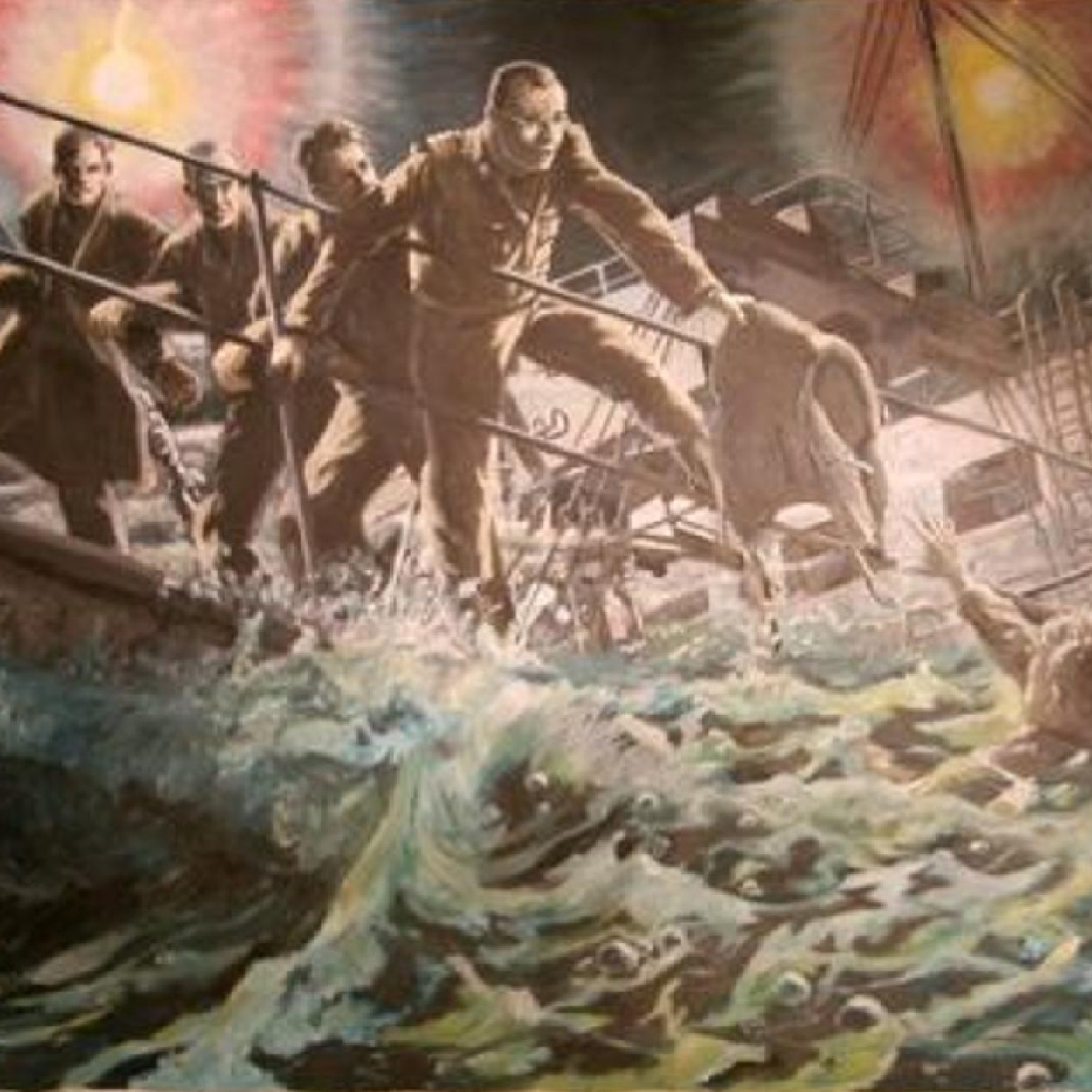

Although healing can be agonizingly long, I know it is possible. After many sacred and miraculous experiences, I recognized that the Lord has been in the many details of my healing journey—leading me along the way, as I was ready, to those who could help me take the next right step. To others walking similarly long paths, no matter what has taken place or how painful the experiences you’ve passed through, please keep going—please keep trying! The Lord can likewise help you find the healing you so desperately seek.

On a particularly challenging day, I recorded in my journal: “Heavenly Father, How do those sinned against learn to feel again, to trust again, to have corrupted experiences of sacred things be healed …?”

Soon after, Elder Patrick Kearon spoke directly to my heart in answer to my heartache—attesting that the Lord Himself “has suffered the very torment you are suffering and endured the very agony you are enduring” so as to “give you the power to not only survive but one day, through Him, to overcome and even conquer—to completely rise above the pain, the misery, the anguish, and see them replaced by peace.”

Long before I began trauma work, I found much peace working with ecclesiastical leaders who eventually taught me how to come unto Christ for help and healing. My parents gave me a most cherished gift when they became members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when I was a toddler. As I learned of the plan of redemption and progressed on the covenant path, I gained hope for myself and my family. Engaging in sacred gospel practices empowered me to overcome great affliction, blessing my family beyond measure. The abuse stopped with me!

The traumas I suffered are not excusable, but they are somewhat understandable—considering past generational abuse issues. Because of church involvement, members of my family are also healing; through the Gospel of Jesus Christ, we are experiencing greater peace and happiness.

As complex and difficult as healing has been for me, it’s exceedingly hard for some to imagine it ever happening for them. How do we help those experiencing ongoing trauma or the memory of it? Exactly how does healing come to pass for those experiencing something so awful they block it out, do not have the courage to break the silence, or fear disclosure, yet no one sees the signs? There are no easy or quick-fix answers.

If we’re serious about helping more of the wounded find answers to such questions—along with protecting the most vulnerable among us from suffering anything like I and the girls in Arizona suffered—we need to ensure that the conversation brings our hearts and minds together.

That’s not what’s happening around us right now, but let’s not give up; we must keep trying!

I believe we can still come together with greater wisdom and love and make progress.