Ever since working at the University of Illinois on research with Nicole Allen, a national expert in family violence, I have kept returning to the same question: What would it take to prevent the abuse of children and women—not only to punish it after the fact, but to reduce the conditions that allow it to keep recurring?

Several years ago, Public Square Magazine provided initial funding for a research team to gather published studies that get at the roots of this question. Our small team reviewed thousands of studies to identify those focused specifically on risk factors making children more vulnerable to sexual abuse by parents, other relatives, or older teenagers.

These studies from around the world also examine the assault of children ages six to twelve and teenagers in various contexts, including competitive sports clubs, youth-serving nonprofits, churches, and schools, with dating violence also receiving much more attention in recent decades.

For many years, scholarship emphasized individual offenders and individual victims—perpetrator motives, disorders, and victim-level correlates. In more recent decades, researchers have increasingly examined the broader context around abuse: family stability, supervision, peer dynamics, institutional oversight, and community accountability—what some studies call “enabling factors” that make abuse easier to commit and harder to detect.

Last summer, I completed this in-depth review of approximately 500 abuse studies (285 involving adults, 215 involving youth), publishing summary versions of results focused on children and adult victims in the Deseret News, with the full-length, 60-page version released later that fall.

This three-part series synthesizes findings from that deep dive into the risk factor research focused on the sexual abuse of young people. Part one outlines five recurring patterns that show up across countries and contexts—patterns that tend to increase vulnerability to child sexual abuse by weakening stability, supervision, and community safeguards.

Fragile Economic Well-Being

Consistently, studies demonstrate that children growing up in families and neighborhoods with limited economic resources are more likely to experience sexual victimization—a risk that appears to grow as poverty deepens (parents unemployed, families going without food, living in substandard housing, adolescents forced to work).

The opposite is also true. For instance, youth whose fathers were employed were “about four times less likely to experience sexual abuse than respondents whose fathers were unemployed,” according to one Nigerian study from 2017.

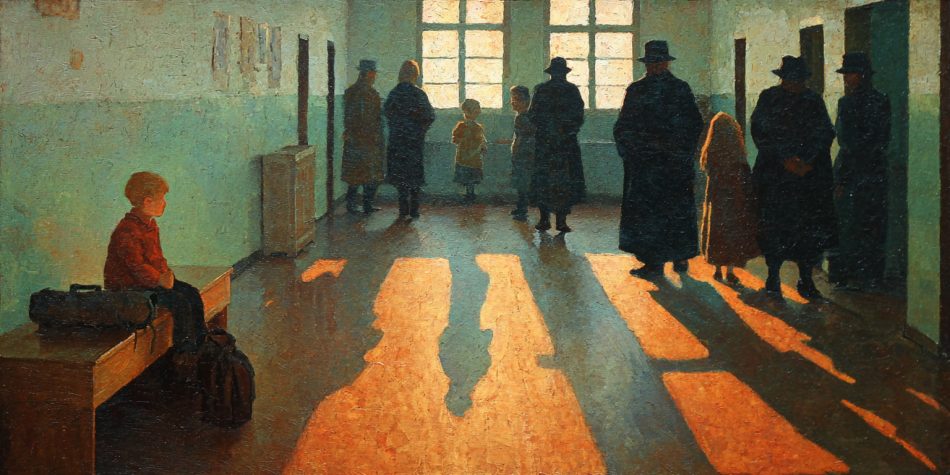

Limited Educational Opportunities

Children with lower levels of education are more vulnerable to victimization—especially those who drop out completely. As Canadian researchers summarized in a 2007 review, “adolescents who have no intention of pursuing postsecondary schooling or who have not obtained their high school diploma are at greater risk of being victims of sexual and physical violence.”

By comparison, when children grow up where education is encouraged and valued, they are less likely to be sexually victimized. This shows up first in analyses of parental education level—with studies from Africa to Brazil to the U.S. showing that boys and girls whose parents have more education are also more likely to be protected against victimization (with risk consistently increasing as parental education declines).

Children’s own higher education level also decreases this risk, starting with just being in school at all. This is especially true if the schools are smaller, if the child feels comfortable at the school, and if they are doing well academically.

Growing Up Without Both Parents in a Loving Relationship

Following parental separation, divorce, or death, a child naturally experiences more residential instability and often significantly less parental supervision. That frequently includes a greater likelihood of being in close, regular contact with other older men who are “not the biological father.”

Children living with both parents are less likely to be victimized.

Consistently, children with incarcerated fathers also were 5.5 times more likely to experience child sexual abuse in one New Zealand analysis. Even higher risk comes when children live with neither of their parents, such as living with friends or another relative; living in foster care or other institutions; or especially if they are homeless and on the streets.

By contrast, multiple studies found that children living with both parents are less likely to be victimized—with the same Nigerian analysis finding children living in these homes “two times less likely to experience sexual abuse.”

Although most sexual abuse happens within homes, studies repeatedly show that children growing up with married parents are less likely to be abused in any way, including sexually. This is especially true when that marital relationship is cooperative and healthy—with “parental togetherness” and “harmony” identified in the Nigerian study as “protective factors that buffer children from sexual abuse.”

No such marital protections exist, however, in the presence of significant amounts of conflict and other kinds of emotional and physical aggression in the marriage and home generally. Another African study found a 2.5-fold increased risk of children being sexually abused when they experienced conflict between parents—a result that aligns with some U.S. data.

Low Quality of the Parent-Child Relationship

While you would expect negative parent-child relationships within any abusive context, there is repeated evidence that poor relationships with a mother and father also precede and predict abuse of various kinds, including sexual violence.

Available studies look specifically at vulnerability to victimization connected to a “lack of closeness” with a parent and “low warmth” relationships within a “rigid” family climate. Children whose parents display harsh, authoritarian parenting behavior are also at greater risk of being sexually victimized.

“Frequent parental monitoring” is connected with less sexual violence.

Also at risk are children whose parents exhibit “laxness of monitoring” and overall neglect. U.S. and Finnish researchers report that “adolescents who had older friends and parents who did not monitor their social relationships were at greater risk of sexual abuse.”

One Canadian study of abusive coaches observed how they often admitted to persuading mothers and fathers to “relinquish some or all parental control” to themselves—with the researchers acknowledging that “for the abused athlete, the bond of trust established between him or herself and the perpetrator is often a substitute for a weak relationship with a parent.”

By contrast, studies in Africa and the U.S. found, unsurprisingly, that “high” and “frequent parental monitoring” is connected with less sexual violence against children and teens. This is also true for positive, warm, healing relationships between parents and children overall.

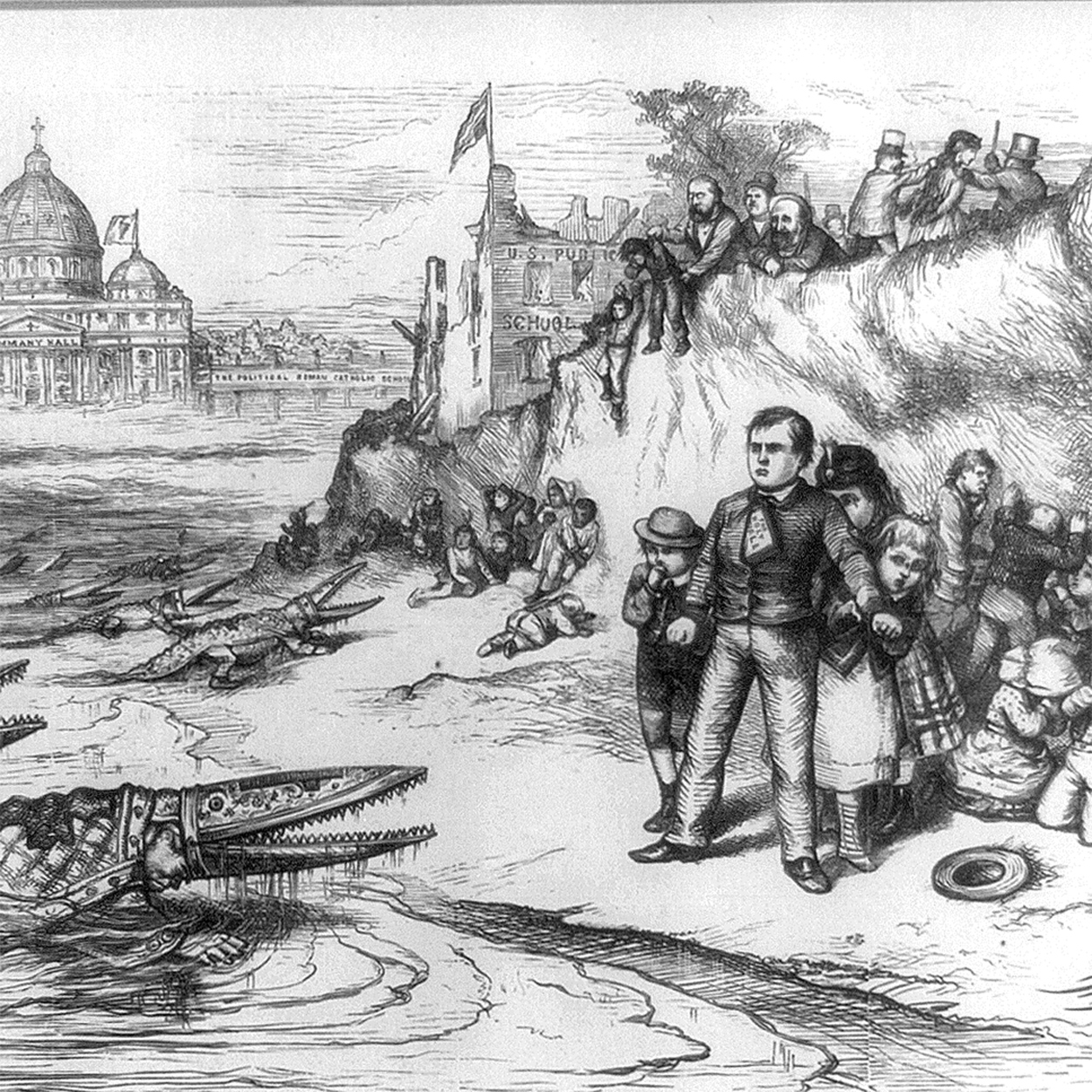

Spotty Community Accountability

To the extent any community has allowed isolated access to children historically, this has sadly been shown to raise the risk of victimization. That includes abuse connected with ‘unguarded access to children’ by religious leaders, ‘unsupervised coaches,’ rogue law enforcement officers, predatory physicians, leaders of boys’ and girls’ clubs, and other organizations where perpetrators can seek out ‘volunteer work with organizations through which they can meet children.’

One study of 41 serial perpetrators found that 57 percent reported having picked their profession either partly or specifically in order to access children. Such privileged, close contact with youth is often taken for granted within special trusted roles—clergy, coach, teacher, mentor, counselor, camp staff, and scout leader.

Healthy peer groups make such a difference.

This is also why healthy peer groups make such a difference, and why negative friend and sibling relationships increase the risk of children being sexually abused. That includes settings where older adolescents have “unsupervised opportunity with younger victims.”

In the absence of this kind of proactive, robust community supervision, what’s clear is that isolation of any kind appears to be quickly exploited by adult and older teenage perpetrators. Australian researchers report that sibling sexual abuse is “the most common form of intra-familial child sexual abuse”—an outcome that is more likely among “step-siblings and half-siblings,” when compared with full siblings.

Five groups of young people, in particular, experience higher levels of sexual violence: (1) girls; (2) younger children; (3) youth who identify as sexual/gender minorities; (4) children who have experienced abuse previously; and (5) children with disabilities—all of whom consistently show higher risk for sexual victimization.

In part two, we turn to patterns tied more directly to mental health, risk behaviors, substances, and the evidence on faith and religiosity—factors that can either amplify vulnerability or strengthen protection depending on how they play out in real communities.

If you or someone you love has experienced sexual assault of any kind and needs additional support in the U.S., contact the National Sexual Assault Hotline (1-800-656-HOPE)—with virtual and text-based options available. This is a confidential networking service in the U.S. that helps connect victims with local agencies that can offer therapeutic support across the country. Similar kinds of hotlines exist in many countries around the world.