I grew up as an actively involved member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Oregon, land of the religious “Nones.” In my circle of high school friends, almost none were church people of any stripe, with the exception of a cute girl I dated until her pastor delivered a scathing and apparently convincing sermon on the “evils of Mormonism” that irreparably divided us. As I learned at a tender age, sometimes religion unites, sometimes it divides.

Yet I also learned that vital religious and life lessons can come from widely varied sources.

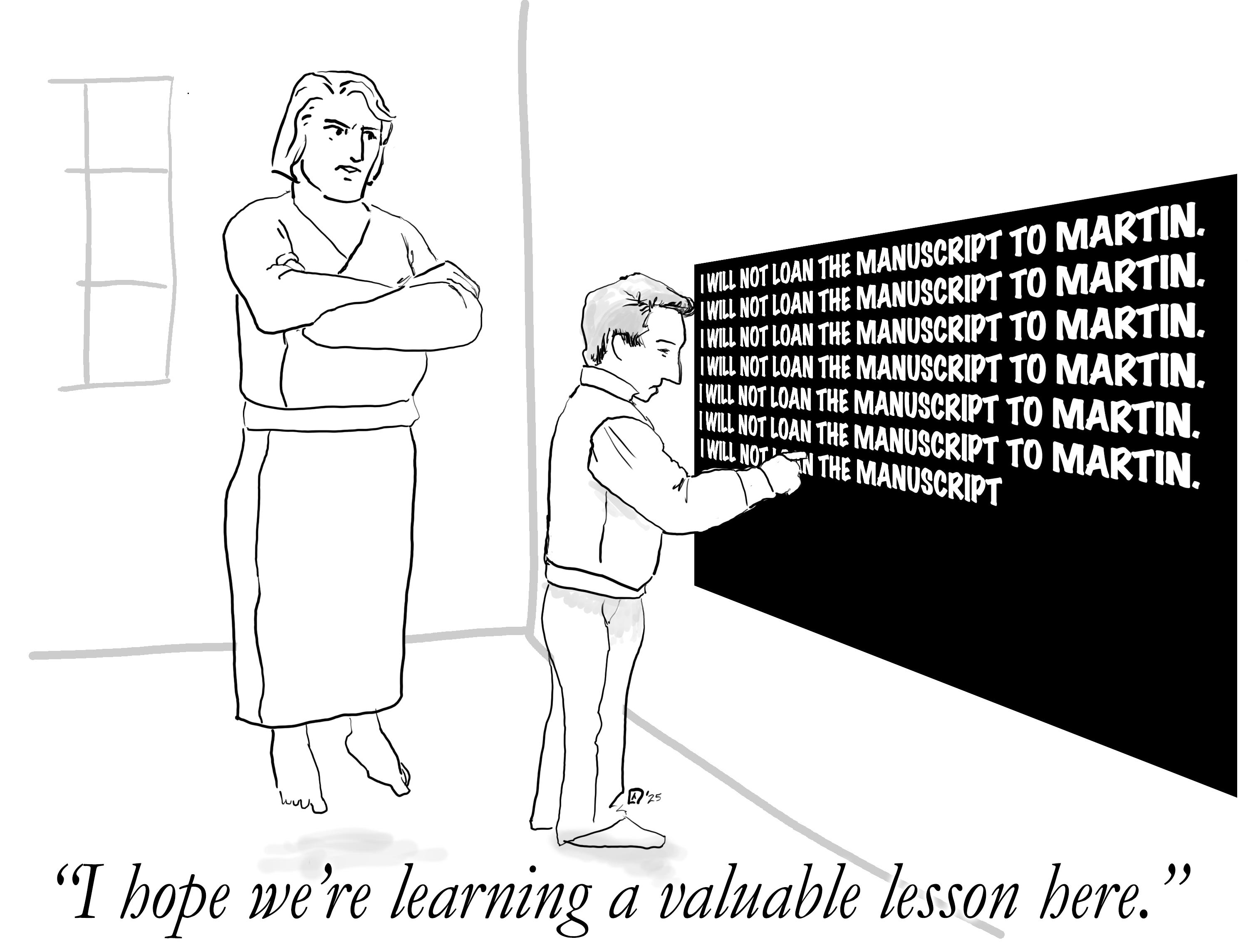

One source of life learning was Tom “Coach” Owens. To this day, despite continued visits together, I have no idea what his religious affiliation is—or if he is a confirmed “None” like many Oregonians. What I do know is this: during my senior year we won two basketball tournaments early in the season with a team that had very little depth. Coach thereafter dismissed three of our strongest members from the team—one for drug use, one for stealing, and one for academic failure. We would lose all but three of our subsequent games that season. If he wanted to, our coach had the needed “pull” to sweep at least one of these violations (which occurred on a team bus trip) under the proverbial rug. Only Coach and the player would have ever known. It was a quiet decision based on integrity.

At one time, Coach Owens ranked number eight on the list of most wins in Oregon high school basketball history. However, he had learned that at its best, basketball is a tool to build boys into men and to teach important lessons, including the hard ones. In watching him, I resolved that I, too, wanted to be a man of integrity and principle.

My two high school camping buddies were, respectively, a hearty hedonist and an avowed atheist tolerant enough to include “the Mormon boy”[ref num=”1″] in their shared worship of the stunning beauty of the southern Oregon coast, with its mountains, rivers, dramatic coastline, and mammoth trees. Their religious tolerance met an epic test, when on a wilderness outing our senior year of high school, my hedonist friend extracted from his car trunk a whole case of wine for non-sacramental use. They knew I would not be partaking, and Ted and Adam looked forward to a two-way split of the spirits. However, knowing a “minor in possession” violation would get me kicked off the basketball team, I had an extreme reaction that I hesitate to even relate. I violated laws of hedonism, atheism, and environmentalism, and commandeered the case of wine coolers and smashed every bottle against a large evergreen tree as my hedonist and atheist friends watched, frozen in disbelieving horror. Ted and Adam somehow refrained from killing me for my prodigality. In retrospect, their restraint probably qualified as a modern day miracle involving wine—although my dear friend Dave Dollahite has pointed out the irony that Jesus provided wine freely, while I ungraciously took it away.

Later that night around the campfire, as we drank soda with widely ranging levels of enjoyment, the topic of our sexual histories arose, and my friends learned that I had no history to report—and that I intended to keep it that way until I one day found a woman crazy enough to marry me. After a long pause, one of my booze-bereft friends, Ted, asked a sincere question.

“Loren, you really believe, don’t you?”

“Yep.”

“That’s cool. I respect you for that.”

One of my first lessons in authentic religious tolerance, forbearance, and respect came not from a member of any faith’s clergy but from a profoundly forgiving 17-year-old hedonist who had just witnessed gallons of alcoholic bliss shatter before his eyes. I still love Ted for that.

As a member of a strong but small faith community, it was necessary (thank heaven!) to reach outside my faith and my own generation for friendships. Two of my dearest friends were a couple of older Presbyterian women—Miss LouElla Kurle and Miss Betty Jean Waite. Both of them were retired school teachers who had given their lives to serving in our community of Brookings, Oregon. I attended a handful of religious services in their building, but what most impressed me was their love and devotion to “their kids” in the community. They rarely missed athletic events and were legendary boosters for both the girls’ and the boys’ high school teams.

I later learned that at least one of the two, Betty Jean Waite, in life and in death, gave significant financial contributions, not only to her own Presbyterian church but also to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and to an Episcopalian church in town. Even though Miss Waite had no formal ties to the latter two churches, she honored different aspects of those churches’ missions and what she saw them striving to do in the community and for others. In the case of the Episcopalian church and their leader, Bernie Lindley, they did (and still do) the beautiful and thankless work of reaching out to the homeless. I learned important things about the kind of man I wanted to be from these marvelous Presbyterian women, and from the quiet example of an Episcopalian clergyman I do not even know.

Another important religious teacher of mine was Wyn Dioletto. I got to know “Grandma Wyn” when she provided a home for her grandson, due to paternal abandonment and his mother’s drug addiction (that she overcame years later). Wyn’s grandson Jeremy and I became friends and her home was always open to me. On multiple occasions, Grandma Wyn, a Jehovah’s Witness, entrusted me as the driver of a group of boys in her car(s) on road trips to Medford, Oregon, nearly three hours away. The first car did not make it back to her due to a blown transmission—and yet she entrusted me with her next car as well. I tried to honor that trust and solemnized our friendship by eating much of the food in her house on a regular basis. She modeled service in all she did for her grandson and she strongly encouraged me to serve a two-year, full-time mission for my church. Until her death, my trips back to Brookings always included her marvelous company—and cooking.

I was a 17-year-old high school senior with little but basketball on my scattered brain when my guidance counselor, Mrs. Marilyn Huslander, hunted me down in the hallway between classes, physically pulled me to the side, and said, “Loren, YOU have not taken the SAT college entrance exam yet and there is only one more chance. I have paid your $40 fee out of my own pocket and you WILL be there to take it next Saturday. Do you hear me, young man?”

“Yes, Mrs. H.”

I did take the blasted test and somehow slipped into college. Mrs. H passed away after I graduated from high school and I drove to her Catholic church in Gold Beach, Oregon, to attend her funeral mass and memorial. I was struck by how many students and former students were there but said to myself, “None of them know that I was her favorite. She even paid for my SAT.”

A light then penetrated my self-centered adolescent brain with the following thought, “Loren, most of the students here today believe that they were her favorite—and that is part of what makes Marilyn Huslander beautiful.”

God bless you, Mrs. H, without you, I may never have made it to college. She is my personal Catholic saint, Saint Marilyn, rescuer of clueless and irresponsible teenage boys. I never paid Mrs. H back her $40. It is a debt that is impossible to repay. Her Christ-like example of reaching out to the one lost lamb still moves and uplifts me more than three decades later.

A little over a year after Mrs. H paid for my SAT exam, I was wrestling with my decision of whether or not to serve a two-year mission for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (a.k.a., LDS Church). Ironically, it was my hedonistic buddy Ted, who paused from frat party carousing long enough to say, “What the hell are you thinking, Loren? You need to go on your ‘LDS trip’ [Ted’s playful combination of LDS mission and LSD trip] and then come back and marry a Mormon girl who is as wonderful as your Mom. You know that!” Angelic and inspired messages are sometimes delivered by earthbound personages. I did serve a mission and it did change my life, but that is another story.

Another influential example in my life was Robert Allsup, my Uncle Bobby. Bobby was a quiet introvert from an Assembly of God background who made the frightening leap of marrying into a family of loud, extroverted Latter-day Saints—Heaven help him.

Bobby and I have shared two loves, basketball and Aunt Doris (“A.D.”), but his greatest impact on me came through observation of his profound efforts to “Honour thy father and thy mother …” (Exodus 20:11). As his mother Lucille aged, he was there for her daily. After her passing, he was there for his father Darrell—morning, noon, and night, year after year. Gentle, caring, solicitous; as consistent as the rising sun. Although he kept the LDS faith at a long arm’s distance, Uncle Bobby was as devoted and faithful an adult son as I have ever witnessed. No Sunday School lesson, in my own church or any other, could teach me more about how to live the “honor commandment” than Bobby’s quiet example of devotion to his parents across decades.

During my graduate school years on the East Coast, I made a dear friend, Pearl Stewart, who also taught me much in her own way. Although from a Black family of modest means, Pearl still gave three years of her life to Peace Corps service in West Africa, allowing both money and time to pass on by. Pearl was my older and wiser sister through our Ph.D. program. She helped me find summer employment, offered sage guidance, and even volunteered to watch our babies for several hours while I took my wife Sandra to a 76ers–Jazz game.

Pearl invited me to attend services with her at her African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, where for the first time in my life, I broke into a full sweat in church trying to keep up with the music. I still treasure Pearl’s warmth, faith, and willingness to serve across boundaries of race, region, and religion. I continue to reflect on her impassioned counsel: “Loren, you know I love you, but you have got to learn to meet people where they are at, instead of where you wish they were at.”

The grad school years also warrant the mention of a dear Jewish mentor, Tamara Hareven. Tamara treated my wife Sandra and me to thousands of dollars in dinners during a time when we could not afford the McDonald’s drive-through. I was touched that she would always call me from Lyon, France, or Kyoto, Japan, before her departing flight to ask me to please pray for her safe and peaceful arrival at her destination. This was not a gentle request but a beseeching. She wanted me to pray over the phone so she could hear the blessing of shalom (peace). I was touched by her faith, except when the calls came between 1 and 4 A.M.

Tamara had almost unparalleled knowledge of family history and was asked by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the early 80s to educate the world’s leading LDS genealogists in some of her unique research methods. She once joshed me, in her thick Romanian accent, “Loren, you served a Mormon mission, yes? And you and your family paid for it?” Then with a dancing twinkle in her eye, she quipped, “I always want you to remember that I was a missionary to the Mormons—and I got paid … handsomely.”

As I reflect on some of the lives that have impacted and blessed my own—a hedonist, an Atheist, a “None,” two Presbyterian school teachers, an Episcopalian priest, a Jehovah’s Witness grandma, a Catholic guidance counselor, an Assembly of God uncle, an African Methodist sister, and a Jewish woman who survived a Nazi concentration camp as a child—I am grateful to have the lasting impressions of noble friends of many faiths on my soul.

I retain a deep and profound love for “my” faith, but if I claim to have any truth in me at all, I must acknowledge that if I am ever to become the man God wants me to be, it has required and will yet require the love, friendship, example, and efforts of a wide array of religious and nonreligious souls to bring that miracle to pass.

[footnote num=”1″] In recent years, we “Mormons” prefer to be called “members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints” but “Mormon” was the common term when I was growing up and no disrespect was intended by my friends in this article who referred to me as a “Mormon boy.”[/footnote]

For additional reading:

Strong Black Families: God, Relationships, and Deep Faith

What is Holy Envy and How Can it Change Our World?

Mainline Protestant Families: Loving God and Family Members

Mainline Protestant Families: Loving God and Family Members

Catholic and Orthodox Christian Families: Confession and Forgiveness

Jewish Families: How Teachings and Traditions Strengthen Marriage and Family Life