When Loren taught a graduate course in family at Louisiana State University, the mostly white class of graduate students had just finished reading nearly 400 pages about Black families in America. Katrina Hopkins, an exceptional young woman from Portland, Oregon, asked, “Why is it that when I read about Black families, I hear about criminality and incarceration and non-marital childbearing and the lack of marriageable males, but I do not get to read about strong, marriage-based Black families like the one I grew up in?”

Silence.

Social scientists tend to focus, if not fixate, on bad news. As in journalism, if it bleeds, it leads. Some demographers are proud of focusing on the Three D’s of “death, divorce, and disease.” Sociologists tend to devote much ink and emotion to fighting what Jonathan Kozol has called “savage inequalities” across race, class, and gender.

In family studies, we found that, for every study focusing on building strong marriage, there were more than 30 studies on divorce. Like most medical and scientific research, our own field is focused on pathology. Sure, it is important to address problems as an essential step towards fixing them, but is there no room at the academic or cultural inn for an occasional celebration of relational health, strength, and wellbeing? Must every hymn be a dirge?

Katrina’s question was a piercing one. Did we have nothing to offer in terms of authentic hope, best practices, and lived models that were imperfect but exemplary? After a couple of days of unsettling mental wrestle, Loren asked Katrina how she would feel about interviewing her parents over Christmas break. She was delighted, did so, and went on to interview many other women and men in strong Black marriages and co-author several related publications conveying health-focused principles instead of pathologies. In this way, Katrina’s insightful identification of a glaring omission and her willingness to do something about it helped commence and grow the Strong Black Families branch of our American Families of Faith research project—a 20-year national effort to interview nearly 300 racially, regionally, and religiously diverse families in healthy long-term marriages. Almost 50 of these families are Black. Is there no room at the academic or cultural inn for an occasional celebration of relational health, strength, and wellbeing? Must every hymn be a dirge?

According to a Pew survey, Black Americans are the most religious racial/ethnic group in the United States. Of Black Americans, 83% identify as Christian and Black Americans attend church more often and rely more on religious communities than white Americans. The most salient themes in the empirical literature on religious Black Americans include a tendency towards a deep faith in an all-powerful, familiar God; and . . . how this deep faith serves as a resource during challenging times.

The high attendance rates of Black Christians provide a rich and deep social network of support that has been associated with lower levels of mental illness and loneliness. The potential benefits extend beyond the psychological and social. In one of the most striking studies we have seen in our careers, the prestigious journal, Demography, published research by Hummer and his research team that found that Black male Americans that attend worship services more than weekly live an average of 13.7 years longer than those who never attend. (Incidentally, an article that Katrina helped write that explored reasons for this difference won a sectional “Paper of the Year” award at a national research conference).

In summary, previous research indicates connections between the religious faith of Black Christians and increases in mental health, physical health, and longevity on a personal level—and with higher quality marital and parental relationships on a familial level. However, we know little about the deeper meanings and processes involved regarding why some Black marriages thrive. Next, we offer a few brief insights gleaned from a recent study entitled, “Weathering the Storm: The Shelter of Faith for Black American Christian Families.” By “giving the mic” to the couples themselves, we are able to uncover some of the underlying reasons for why and how religion reportedly influences many strong Black marriages and families.

Many participants expressed how God helped with “the cares of life” and gave them strength. A mother named Jocelyn (all participant names are pseudonyms) said:

There’s somebody much greater than you who can carry those burdens for you, and you don’t need to be up all night worrying and caring, going through the cares of life, because scripture teaches us that we can cast all our cares upon the Lord. For He cares for us and He’s gonna take care of us and He’s gonna sustain us.

A mother named Monique spoke of God’s active role in her life’s trials:

I think that no matter what happens in our lives—and there have been some negative things, even aside from [our serious car] accident—you can always go [to God]. [W]e believe in what God says in His word, and there’s always something in the word that will make it good. . . . [W]e believe that all things work together for good, so even if the things aren’t good, we know that God is . . . there. . . . [W]e know that we’ve got a source of strength.

Monique’s oblique reference to Romans 8:28 (“[W]e know that all things work together for good to them that love God . . .”) was echoed by other mothers and fathers, across denominations.

In addition to a belief in a God who “cares,” “sustains,” and helps “things to work together for good,” many Black women and men emphasized that “the power of prayer gets us through.” One mother shared:

One strong belief that I have is in the power of prayer. I do believe that prayer will get you through any[thing] and everything . . . that’s my testimony. I know that I can go to God in prayer and even if I pray and I don’t get the results that I’m seeking, the Lord does give me peace to know that He has heard my prayer. And just because I don’t get the answer I want . . . does not mean that He has not . . . heard or answered my prayer.

A father named Jamal shared how the “prayers of others” reportedly helped him through a particularly challenging time:

It may not have been [my] prayers, but it was prayers of others that helped [me] get through those hard times. . . . [M]aybe that’s why a lot of us don’t have [more] hard times. It may not always be our prayers, it may be prayers of others. (See this article for more on this topic).

A mother named Jocelyn offered a glimpse into her life approach to personal prayer. She said:

I don’t have just one special time that I set aside to meditate or pray . . . I do it all day long. I do it in the course of my workday, driving in my car, in my home, in my bed . . . and that helps me make it through challenging times. When I’m faced with a difficulty, no matter where I am, I can always whisper a prayer to God and just ask for His strength to sustain me when I’m going through some things. It helps. It does.

When asked about sources of strength that helped His marriage, a father named Calvin said, “[I have] constant conversations with the Lord, in good times and in bad.” Another participant explained that she did not try to fit her faith into her life, but that my “faith is [my] life.” Many participants shared with us reports of a deep faith without temporal boundaries. Their faith was not a Sunday practice or even a morning and evening ritual, it was an “all day long” commitment—a commitment frequently challenged by work, financial struggles, racism, and the “burdens of life.” We will return to these burdens shortly.

The belief that marriage is sacred or “ordained” by God was expressed widely by our Black participants, for whom marriage was a holy commitment involving God. A wife named Gwendolyn expressed her belief in marriage as a sacred institution:

[Y]ou both want a marriage that lasts and you want your marriage to glorify God. You want it to be an example of Christian principles and biblical principles. And you make up your mind that my marriage is going to testify of Christ. And when you both say you are going to do that, you don’t let the little things interrupt that.

A husband named Randall shared similar thoughts regarding the sacred nature of marriage, as well as how that perspective helped him and his wife Tanya work through differences in their marriage. He explained:

We’re individuals. We battle, and a lot of times, she [doesn’t] like the differences in me, and a lot of times, I don’t like the differences in her. But because we both believe that marriage is a sacred vow, and that it’s a vow we took before the Lord, we’re gonna honor that vow, and we’re gonna go through with it. And we said the same vows, “For better, for worse, in sickness and health, for rich, for poor.”

Another husband named Rashaad expressed:

We both feel that a marriage is a bonding thing. As He says, “Whatever I join together let no man put asunder.” I believe that my faith made me love my wife a lot more. We are very different. If it weren’t for faith, I probably would have run a long time ago. “You don’t want to do what I want to do. We just don’t see eye to eye. I’m gone.” But when you believe in God . . . yes, the boat still gets to rockin’ but the Bible says, “In me you can weather the storm.”

When asked about advice she would offer to young Black couples about marriage, Raven replied:

They need to realize that marriage is God’s design and you can’t truly experience marriage without having God be a part of it. When God is part of your marriage, that’s when you can experience the true fulfillment of what a marriage is. The two come together and they may be different in many, many ways. But when they come together and love each other and respect each other and do marriage the way God has designed it to be, it’s very fulfilling.

Most of the couples we interviewed were referred to us as “exemplary” by their respective clergy—we wanted to interview couples who not only were “still together,” but who were exceptional. We were therefore surprised when one-fourth of the “exemplary” couples we interviewed spontaneously told us that without God, they would have divorced long ago. Had we asked, we suspect the figure would have at least doubled. Our image of “exemplary” marriages was transformed from a “marriage without significant problems” (there likely is no such thing) to a “marriage where the partners unite to face their problems.”

One wife and mother spoke of how “the word” helped with her marital ups and downs:

We have our ups and downs and our differences and disagreements, and I think being able to go back to the word and read scripture and [to see] what scripture says about it helps. That is my roadmap for my life and for my marriage.

Many Black parents spoke of God and emphasized the importance of a relationship with Him. One mother, Kayla, explained how this focal “relationship” influenced her parenting. She said:

In raising kids, you want to teach them to take everything that happens in their lives to God, whether it’s a test or whether it’s a decision about if they’re gonna go to the prom or go on a certain date . . . just to make God the focus of it and include Him, because it is a relationship more . . . than a religion.

Orlando referenced fatherly “responsibilities” as outlined by God:

The more that I study about my Creator, [He] really . . . outlines my role . . . and what my responsibilities are. And what that means to me is to really embrace [my family] with all the heart and all the love that I have. . . . [T]he life that I have and the world that I live in sometimes are opposing each other. This world tries to pull people apart, but through my religious faith I’m able to hold my family and the people I love together [even though] I know that there’s a force that’s working against love, peace, and harmony.

Orlando later spoke of how his faith influenced his feelings of familial responsibility:

There is a higher standard, there is a much higher standard I’ve learned about, and what that standard means . . . is that with this life that I have, I must give my life for my family.

Tara shared a similar sentiment, selecting the word “obligation” in connection with motherhood:

I have a strong commitment to family and I feel an obligation to our kids. Once you have children you have an obligation to present to them a marriage or a family so that they can . . . [know] what it looks like . . . and what it feels like, so . . . they’ll know what’s right.

Other Black parents explained how the love they felt from God helped them to better love themselves and their children. They also spoke of the importance of showing affection. A father named Marcus shared his related perspective that:

In order for me to love my kids, I must first love myself. So when the Lord loves me and I get to know who I am and get to love myself, then I can reach that love out to [my kids]. The love I have for them is the same kind of love [God] has for all of us. . . . [At least] one time in the course of every day, I tell my kids, ‘I love you,’ give ‘em a big hug . . . hold ‘em, let them know I care. I let them know I love [them]—not because it’s just the thing to say, but because I DO. And [I tell them], ‘God loves you too.’ So even when we do go through little life struggles, it’s okay, because someone who loves them is going to be there throughout the good and the bad.

Similarly, when asked what advice she would give to other Black couples about marriage and parenting, a mother named Jacqui said: “Always remember to tell each other that you love each other. Don’t be afraid to hug, [to] embrace. . . . [L]et your children see you embracing.” This image of a loving marital embrace with the love of two parents flowing towards the children is the lost story that Katrina needed to have told. Issues such as absentee fathers and single-parent homes, have dominated research on Black Americans since the Moynihan Report in 1965, while the notable strengths of Black families have been overlooked. “The life that I have and the world that I live in sometimes are opposing each other. This world tries to pull people apart, but through my religious faith I’m able to hold my family and the people I love together.”

Our own research has revealed several noble features that have elicited our “holy envy.” Contextually, we note that 80% of the marriage-based Black families we interviewed hailed from inner-city contexts. These were often blue-collar families whose married status was the exception on streets lined with single-mother families, poverty, and need. For these families, the United States is not a “post-race” nation. Poverty, often deep poverty, as well as unemployment, inadequate educational opportunities, discrimination, incarceration, and many other social ills were far too familiar.

We have called many of our married couples “wealthy poor”—if your income is $30,000, you are wealthy compared to your neighbors with one-half or one-third of that. Accordingly, these marriage-based families were often the first to receive “knocks of need” (requests for money, help, and even temporary housing) from the less fortunate who surrounded them. It is telling that every Black family we interviewed had taken in at least one “temporary child” who was not their own at some point. One couple had taken in so many children at varying times, they weren’t even sure of the number.

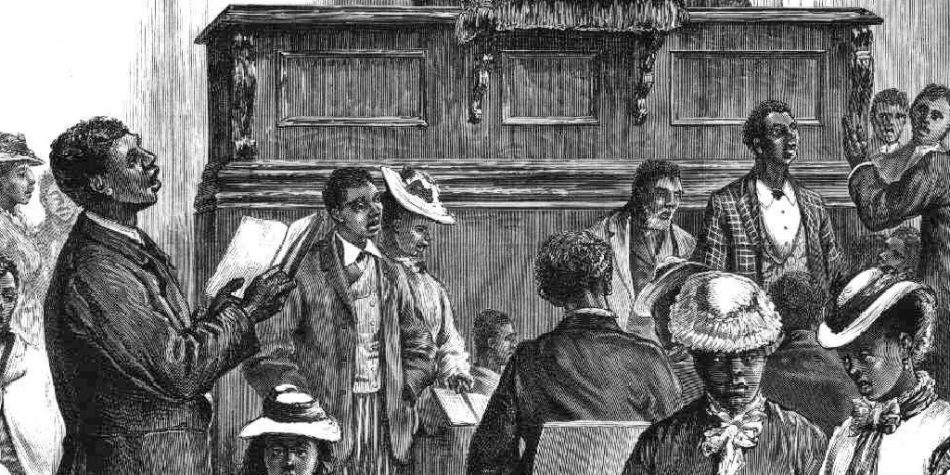

The lived religion of most of these families was not a sanitized, upper-middle-class spirituality, it was a desperate, profound, and pleading faith of survival that, even in 2021, still contains echoes of the mournful notes of the shame of American slavery. Theirs was not merely a faith that enriched or added meaning to life. Their faith was often life itself.

While we cannot claim to envy the plight of one of the most discriminated-against groups in U.S. history, we do envy the profound depth of their living faith in and relationship with a personal God that heard and sustained them through pain and storms. Like Katrina, we want you to know that such families exist and that because of them, our world is a better one.

About the Authors: While we ourselves are active (devoted) members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, in our work in the American Families of Faith project, we seek to highlight the strengths of our friends of various faiths. We have developed a sense of deep respect and even holy envy for these families and their faiths. Additionally, the book chapters from which these articles are adapted each included two coauthors who are devoted members of those faiths.

If you like listening to audiobooks and podcasts, we have recorded a set of conversations about the families we interviewed that includes additional quotes from mothers, fathers, and youth, more of our experiences in attending their services, as well as personal experiences with friends of other faiths. These podcasts are available at: