In modern culture, we worship the new, the young, and the future. We seek out a new theory, the next fashion, or a fresh perspective. This “cult of progress” reaches deep into academia. I was a research assistant for several social science professors at a university where the pressure to publish weighed heavily upon them. To be published, you must come up with something “new” and eye-catching in your research. If your work included a paradigm-shifting idea, your chances of publication dramatically increased. Research is now conducted with the goal of being original. Interview questions are composed, phenomena described, and statistics analyzed in the hope of catching the eye of a prominent research journal.

This modern emphasis on over-valuing the original and distinctive features bothers me. I find it hard to believe things presented as “new.” If, in the thousands of years of human thought, no one else “made the connection,” is it worth making now? There is often a deep arrogance in supposing that what is new is better. This is how we end up with Reese’s peanut butter cups with potato chips in them.

Much of my disillusionment with modern thought started in high school. My mother encouraged me to read The Brothers Karamazov by Dostoyevsky. That book changed my life and my perspective. How could an author from 19th Century Russia speak so deeply to my 1990s heart? I continue to be amazed by the wisdom found in even more ancient writings. From Aristotle to Chesterton, the long-dead still speak to my soul. When I compare much of our modern culture to antiquity, it seems clear that standards are lower. Old Town Road was a #1 song after all, and in 1750, even Bach wasn’t good enough. He only became popular after his death.

Progress on Wise Backs

We certainly have made progress. We live in the age of novocaine and indoor plumbing. Much of our most tangible progress has been made in the hard sciences—technology, engineering, science, and medicine. The advances made in these fields are truly staggering. Yet, when we compare rockets going to Mars with recently published research in sociology, the difference in quality is quite stark. So why have the hard sciences advanced while the arts and social sciences haven’t as convincingly? Hard sciences are humble. They know that progress is only made on the back of previously gained knowledge. But in the “softer sciences” and even in our own lives, we frequently presume the opposite—think we can leave behind and ditch the “old.” We take for granted they were “backward” in earlier eras; that the world has changed fundamentally since then and that we have evolved and advanced beyond their morality. Really?

We are the descendants of generation upon generation of deep-thinking human beings—generally more deep-thinking than ourselves. If you doubt it, read a letter written by the average uneducated soldier in the Civil War. The eloquence and depth found there will leave us ashamed of our emoji-laden texts. We take for granted they were “backward” in earlier eras; that the world has changed fundamentally since then and that we have evolved and advanced beyond their morality.

That fame and recognition, of course, pull on our ambitions every day online across various social media channels. Who could not be somewhat allured by the pull of what is popular? Yet as C.S. Lewis said in his book The Problem of Pain, “I take a very low view of ‘climates of opinion.’ … All discoveries are made, and all errors corrected by those who ignore the climate of opinion.”

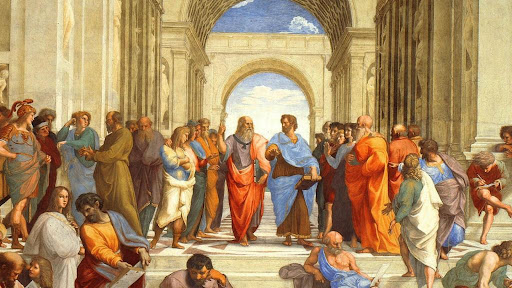

While the climate may change, ultimately, there are no “new” philosophies. Plato, 300 BC, would not be surprised by any arguments for justice and equality made by Marx or in Critical Race Theory. Thrasymachus, a character in the Republic, argued “might makes right” thousands of years before Nietzsche.

A.N. Whitehead said, “The safest general characterization of European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato.”

There have been hedonists, material determinists, polyamorists, utopians, anarchists, etc. since we started writing down ideas. The human mind has many centuries of experience going deep and shallow, skeptical and faithful, pessimistic and optimistic, far and near. Our ancestors’ moral backwardness is only equaled by our own. Our sins are not unique; our virtues are not “progress.”

The author of Ecclesiastes suggests, “What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun.” Later, we read from Paul, “There hath no temptation taken you but such as is common to man.”

However, we see that some of these old philosophies become predominant over time. Scientific materialism, while adopted by a small segment of philosophy, such as the Sophists in Greece, now rules our scientific community. And moral relativism is now the hidden tyrant of modern social science. So, while there is nothing new under the sun, some trees have grown so large that they block out the sun of all other philosophies, particularly any that claim objective truth. (I recommend Stephen C. Meyer’s The Return of The God Hypothesis, where he discusses the relatively recent rise of materialism in science.)

Classical Education

Previous generations valued “classical education.” They looked to the wisdom of the past before disdain for the old became the dominant philosophy. The moral progress we can claim, such as the abolition of slavery in the West and equal treatment under the law of women and minorities, was achieved by men and women who respected and utilized the scholarship of the past to make advancements in modern times (Check out this clip from Catholic Bishop Roberton detailing the influence of “old” Christian ideas and traditions on the civil rights leaders of the past, including Martin Luther King, in sharp contrast to the modern progressive movements which are often antagonistic to such tradition.)

Rather than labeling the imperfect men and women of the past as unworthy of their time and attention, previous generations accumulated wisdom by reading “the greats.” To be “educated” meant to have common knowledge of key works of literature, philosophy, art, and music. While there are still many private schools and home-school curriculums that provide a “classical education,” focusing on teaching great works of logic, art, and literature, the prevailing view of being “educated” is very different. At university, we are schooled primarily in criticism and how to identify the failings of past scholarship. We are encouraged to read works from earlier eras seeking out biases and agendas far more than truth. We are to be the judges of our predecessors, not their students.

We return to C.S. Lewis, this time in his book The Screwtape Letters: “The Historical Point of View, put briefly, means that when a learned man is presented with any statement by an ancient author, the one question he never asks is whether it is true.”

Universities are now dropping requirements to study classical literature such as Shakespeare and Homer. A piece in the National Review described the reason behind the decline in teaching the classics: “Critics believe that the study of classics ‘has been instrumental to the invention of ‘whiteness’ and its continued domination.’”

This is folly. The traditions and philosophies of the past were built on the backs of millions of minds gathered together for the benefit of mankind. Why throw that away? We need not accept every tradition, every past belief—for human vice certainly influenced the development of many. But surely we can learn from our intellectual ancestors. We now have an expanded ability to pull knowledge from various cultures and religions—great thoughts were thought in every land. But let’s not toss out what has proved beneficial and enlightening because it is “western” or “old.” We need to read Shakespeare. There will never be another like him.

Referring to Christ, George MacDonald once said, “Our Lord never thought of being original. The older the saying the better, if it utters the truth He wants to utter.”

When I look at our modern world, it is clear we are missing something: we are missing something old. C.S. Lewis describes this old and deep wisdom as the Moral Law, written in the heart of every man. Because all men through all ages have had contact with this Moral Law, we can look back in confidence that they were not, in fact, simply morons. Practical morality may differ between cultures, but there are commonalities among all cultures because the idea of right and wrong is innate.

G.K. Chesterton in his book Orthodoxy said, “The soul might seek the strangest and most remote lands and ages and still find essential ethical common sense.” And Aristotle said in Rhetoric, “There really is, as everyone to some extent divines, a natural justice and injustice that is binding on all men, even on those who have no association or covenant with each other.”

While Aristotle understood that different cultures have unique laws, social stigmas, and customs, he emphasized that universal law must undergird these “particular laws,” or we will end in moral chaos.

No Boundaries, No Truth, No Respect for the Old

Henry David Thoreau said, “Every generation laughs at the old fashions, but follows religiously the new.” Today, as we increasingly and overtly reject the idea of a moral law or transcendent truth, the wisdom of the ancients becomes irrelevant. Progress, to many, means moving beyond any fences, any morality which may stifle us. Our customs and our new traditions need not be “good” to be acceptable; they simply must be accepted to be acceptable.

In The Thing, G.K. Chesterton says, “[Consider], a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, ‘I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.’ To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: ‘If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.’” Chesterton continues by explaining:

If he knows how it arose, and what purposes it was supposed to serve, he may really be able to say that they were bad purposes, that they have since become bad purposes, or that they are purposes which are no longer served. But if he simply stares at the thing as a senseless monstrosity that has somehow sprung up in his path, it is he and not the traditionalist who is suffering from an illusion.

We are tearing down fences without considering why they were built. We tore down sexual morality; are we better off now? As we tear down the constraints and encouragements of religious dogma, are we more compassionate and happier?

The Wickedness of the Past Guides us to Future Righteousness

Let’s be clear—the past was certainly not full of virtue. Ghengis Khan and Vlad the Impaler could have benefited from reading Plato, too. The past has been full of wickedness. Morally, we may be no better than them, but they were arguably no better than us either. Vices like envy, greed, and the drive for power have always lived side by side with virtues. As much as we can learn how to be good from our ancestors, we can also learn how they went bad.

We can read from the words of the wise who lived in dark times—“saints” who sought to pull people out of the darkness and back towards the light of morality. These greats of the past were often those most rejected by the people of their time or honored for their bravery in pointing out their society’s excesses. Sound familiar?

Again we read from G.K. Chesterton, in his biography of St. Thomas Aquinas, explaining that the “Saint” is often a “martyr” because “he is mistaken for a poison because he is an antidote”— adding:

He will generally be found restoring the world to sanity by exaggerating whatever the world neglects … he is not what the people want, but rather what the people need. Therefore it is the paradox of history that each generation is converted by the saint who contradicts it most.

Seek Out the Old to Build a Better Tomorrow

We all seek a better future—a Utopia, a Zion. Young people especially believe we can build a better world. I pray they are right. But how do we build it? We have rockets going to Mars because wise scientists still read Einstein and Newton. Can we build a Utopia without Aristotle? Without Jesus Christ?

I believe it is time to revisit the wisdom of the past. We must read old books and point our idealistic youth to them. If we gather wisdom from the ages, we are much less likely to be swayed by the fads of the day—the modern trends that will fade into history like so many before them.

C.S. Lewis warned against focusing our study on modern books alone, “Where they are true they will give us truths which we half knew already. Where they are false they will aggravate the error with which we are already dangerously ill. The only palliative is to keep the clean sea breeze of the centuries blowing through our minds, and this can be done only by reading old books.”

Nothing New for Christians

I had an interesting encounter online recently with a young man, a devout atheist. He was protesting one of my pieces, which I am fairly certain he didn’t actually read. His retorts were right out of the atheist scriptures: “If God were good, why would he let children die painfully?” and “Why doesn’t God just show himself?” In speaking with this young man, it became obvious that he thought these questions were “new” ideas that Sam Harris or one of his other idols had originated and which now “debunked” religion. He was surprised when I pointed him to old philosophy that answered his “new” doubts. Our customs and our new traditions need not be “good” to be acceptable; they simply must be accepted to be acceptable.

God doesn’t conform to the “climate of opinions;” He deals in ancient laws and truth. He has seen all vice, all trends, all doubts, all the tactics of the adversary, and He gave us their remedy 2022 years ago. While we certainly have modern challenges, divine solutions to them are unquestionably old—even while they continue to be continually relevant, even “new and everlasting.”

Even in our faith communities, the worship of the “new” thrives—manifested in the vaunting of a different interpretation of scripture, a modern understanding of doctrine, or a new movement we should adopt into the gospel. Each idea is accompanied by hundreds of voices backing or refuting it on social media. While there is value in this wealth of information, we must not lean too much on others’ interpretations or trust excessively in those who must keep audiences entertained (I include my own writing in this criticism). Our wealth of resources, even in ancient wisdom, can quickly turn to excess, to noise. It becomes more difficult to remember which principles are “first” as we become preoccupied with peripheral doctrines. We may need to return occasionally to the pure word of God to praise—to the ancient gospel of joy and simplicity.

In The Screwtape Letters, a demon explains with disdain the stillness of a “believer’s” home as a “sickening resemblance” to how one writer described heaven, namely “the regions where there is only life and therefore all that is not music is silence.” The demon continued, “Music and silence—how I detest them both! …[Hell] has been occupied by Noise. We will make the whole universe a noise in the end. … The melodies and silences of Heaven will be shouted down in the end.”

We have collected so much wisdom at an ever-increasing rate, it has become noisy—endless Christian podcasts, articles, and Facebook groups. Our abundance can be stressful and unsteadying. Our ancestors treasured their copy of the Bible and, if they were lucky, The Pilgrim’s Progress or Book of Common Prayer. They were no less righteous for the lack.

If we find ourselves overwhelmed or overly influenced by the new, by the excess, we should retreat to the melodies and silences of Heaven. When it is time to dig more deeply into wisdom, let us not forget to reach for the words of our ancestral teachers. As we stop valuing originality, but rather value truth, we may discover that what we truly seek is very old indeed.

_______________________________

Further Quotes on the Value of Modern Arrogance and Ancient Wisdom

“In place of the old beliefs of a civilization based on godliness, judgment and historical loyalty, young people are given the new beliefs of a society based on equality and inclusion, and are told that the judgment of other lifestyles is a crime. … The ’non-judgmental’ attitude towards other cultures goes hand-in-hand with a fierce denunciation of the culture that might have been one’s own.” ~Roger Scruton

“The two most potent post-war orthodoxies—socialist politics and modernist art—have at least one feature in common: they are both forms of snobbery, the anti-bourgeois snobbery of people convinced of their right to dictate to the common man in the name of the common man.” ~Roger Scruton

“My attitude toward progress has passed from antagonism to boredom. I have long ceased to argue with people who prefer Thursday to Wednesday because it is Thursday.” ~G.K. Chesterton, New York Times Magazine, 11 Feb. 1923

“Men invent new ideals because they dare not attempt old ideals. They look forward with enthusiasm because they are afraid to look back.” ~G.K. Chesterton “The Unfinished Temple,” What’s Wrong With the World

“Tradition means giving votes to the most obscure of all classes, our ancestors. It is the democracy of the dead. Tradition refuses to submit to that arrogant oligarchy who merely happen to be walking about.” ~G.K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy

“Only the learned read old books and … they are of all men the least likely to acquire wisdom by doing so.” ~C.S. Lewis, The Screwtape Letters

“It is always easy to let the age have its head; the difficult thing is to keep one’s own. It is always easy to be a modernist; as it is easy to be a snob.” ~G.K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy

“In the first place [Barfield] made short work of what I have called my ‘chronological snobbery,’ the uncritical acceptance of the intellectual climate common to our own age and the assumption that whatever has gone out of date is on that account discredited. You must find out why it went out of date. Was it ever refuted (and if so by whom, where, and how conclusively), or did it merely die away as fashions do? If the latter, this tells us nothing about its truth or falsehood. From seeing this, one passes to the realization that our own age is also a ‘period,’ and certainly has, like all periods, its own characteristic illusions. They are likeliest to lurk in those widespread assumptions which are so ingrained in the age that no one dares to attack or feels it necessary to defend them.” ~C.S. Lewis, Surprised by Joy

(Advice from one demon to another) “The use of Fashions in thought is to distract the attention of men from their real dangers. We direct the fashionable outcry of each generation against those vices of which it is least in danger and fix its approval on the virtue nearest to that vice which we are trying to make endemic. The game is to have them all running about with fire extinguishers whenever there is a flood, and all crowding to that side of the boat which is already nearly gunwale under.” ~C.S. Lewis, The Screwtape Letters

“To regard the ancient writer as a possible source of knowledge—to anticipate that what he said could possibly modify your thoughts or your behavior—this would be rejected as unutterably simple-minded. And since we cannot deceive the whole human race all the time, it is most important thus to cut every generation off from all others; for where learning makes a free commerce between the ages there is always the danger that the characteristic errors of one may be corrected by the characteristic truths of another.” ~C.S. Lewis, The Screwtape Letters

“It is obvious that tradition is only democracy extended Through Time. It is trusting to a consensus of common human voice rather to some isolated or arbitrary record.” ~G.K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy

“Tradition means giving votes to the most obscure of all classes, our ancestors. It is the democracy of the dead. Tradition refuses to submit to the small and arrogant oligarchy of those who merely happened to be walking about. All democrats object to men being disqualified by the accident of birth; tradition objects to their being disqualified by the accident of death.” ~G.K Chesterton, Orthodoxy