Increasingly, I get the feeling that educated friends, relatives, peers, and acquaintances leaving the Church aren’t leaving the Church so much as they are joining—what exactly? Something else. They’re not becoming Catholics or Presbyterians or Muslims or going through any deliberate conversion process. It’s something a little different. If you ask them about it, they’ll probably be confused—denying they are joining anything at all. They’re just growing apart from the Church. If anything, they say, it’s the Church that, having become too toxic or conservative or dogmatic, has left them!

Yet their “it’s not me, it’s you” stories don’t quite add up. Church messaging has, if anything, become more accommodating and less hard-edged over the last few decades. Church leaders from apostles down to bishops are pouring enormous amounts of energy into listening, talking, praying, and planning, trying somehow to help. There have never been more resources available to those struggling with their faith. But these outpourings are often met with indifference and grimacing glances in the other direction. “It got to the point that we felt we should set up an evening class for those struggling with these issues in our ward,” one bishop told me recently, in a story that felt very familiar. “We got a couple of excellent and knowledgeable facilitators who were prepared to dig into all the thorniest issues. There were a lot of struggling members who had told us they wanted answers. But then the day of the class came and nobody showed up. I don’t get it.”

The strange disaffection continues. I recently put my finger on what the feel of it was. Namely, the feeling is that of a marriage in which one spouse gradually-then-suddenly loses interest in the marriage, to the confusion of their partner. The faithful spouse, terrified, searches desperately for the faults of their own which must have caused the rift, redoubles their efforts to work on the marriage, begs their partner to stay, assumes their spouse’s complaints are in good faith, forgives increasingly hostile behavior … but the overtures, if anything, seem to make things worse. The wayward spouse is contemptuous and indifferent and continues drifting and turning away until the marriage suddenly ends. Some weeks later the faithful spouse discovers their beloved had simply fallen in love with someone else, become unfaithful, and left.

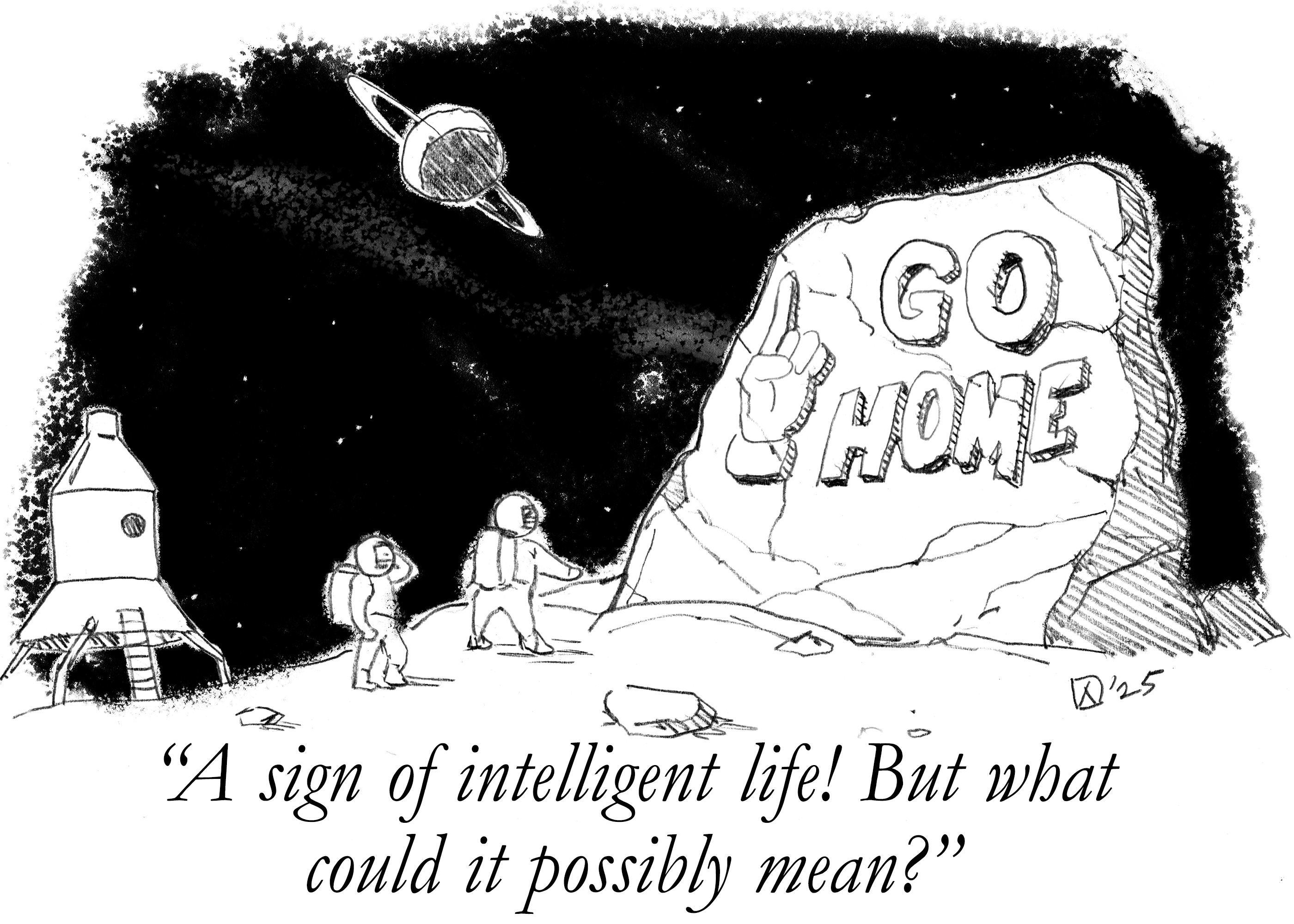

This comparison captures an important dimension, I think, of the relationship between the Church and its disaffected members. But if the Church is the faithful spouse and disaffected members the delinquent beloved, where is the other lover? Who is the homewrecker? This is, if you ask me, the most underrated question in the discourse. “Leaving the Church” is only half the story. When it comes to educated white members in North America drifting into dissent and disaffection, there is indeed another lover—another religion—in the picture. It’s just hard to see at first.

Almost immediately after writing the paragraphs above, a recent article of Dan Ellsworth’s popped up in my feed. In the article (which you should read if you haven’t), Dan makes the same comparison I make to marital disintegration, toward a slightly different point. “Just like ancient Israel,” he says, “I believe we are facing as a people an epidemic of emotional affairs with a variety of extra-covenantal influences that are poisoning our vertical and horizontal covenant faith commitments, leading many church members to adopt the compare-and-criticize behaviors that are fatal to covenant joy.” Dan recommends “pruning our social media consumption” and unfollowing influencers who might be leading us astray in whatever direction. The faithful spouse, terrified, searches desperately for the faults of their own which must have caused the rift, redoubles their efforts to work on the marriage, begs their partner to stay…

It’s missing the big story, if you ask me, to think of this strange disaffection as an epidemic of individual affairs as if church members are spontaneously becoming less virtuous and more prone to unfaithfulness. Rather, it’s more like one collective love affair whose proximate cause is, simply, the appearance (circa 2013) of an appealing new lover. There have always been seductive influences on the fringes of our faith, but, at least among educated white North American members, there is only one competing religion that has left the fringes and begun exerting its influence on almost everyone. It’s the official religion of our social class, the one with influence in practically every institution, and the one that does not regard itself as a religion because it does not have to.

It doesn’t even have a name (its adherents refuse to acknowledge it exists, let alone to name it), and I hesitate to identify it because it gets circumscribed into “politics.” It’s wokeism, or social justice, or critical theory, or baizuo-ism, or the successor ideology, or contemporary American progressivism. It’s the religion whose taboos you and all your peers know implicitly and must observe if you would like to get or keep a white-collar job. It’s the reason you can’t watch a movie from ten years ago without having alarm bells go off subconsciously—because even if you don’t accept the critiques you can make them as well as anyone because you hear them constantly.

I mean it literally when I say it is a religion. It’s a comprehensive worldview with taboos, authority, myths, sacred objects, a moral framework, and unfalsifiable beliefs. And I don’t mean “religion” as an insult: contemporary American progressivism isn’t bad because it’s a religion, rather, it’s bad because it’s a false religion. But even more, it is dangerous because most people, inside or out, don’t recognize it as a religion.

I’m clearly not the first to make this observation. In 2018, John McWhorter, a writer and professor of linguistics at Columbia University, observed that in the previous few years, “social justice warrior ideology” among his students had started to look more like religion. “And I must make it clear that when I use the word religion, I don’t mean it as a battering ram. I don’t mean it to be funny. I mean that there actually is something that has settled in, in our campus discussions now, that an anthropologist from Mars would recognize as no different from, for example, strong Christian fundamentalism.”

But he noted that adherents do not see it this way:

In 1500, nobody in Europe considered themselves religious. It was just in the water. If there was such a thing as an atheist, they kept that to themselves … that’s where we are now. And so many of the people now who are religious would resist the label because especially a modern, secular, educated person often won’t like the idea of being told that they have a religion. But that doesn’t mean that the analysis isn’t accurate. There’s a religion.

In this important sense, contemporary American progressive religion, the theological water in which educated people in our society swim, is postmodern to the point of being … premodern. In most cases, believers simply do not know they are a part of it. Even most non-believers don’t see the religion for what it is.

For a recent illustration of the strange encounters this dynamic gives rise to, consider US Sen. Marsha Blackburn’s recent question to Supreme Court nominee Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson: “Can you provide a definition for the word ‘woman’?” In an important sense, the question was deeply inappropriate. It tried to force someone to confront a paradox at the heart of their religious worldview. In contemporary American progressive theology, maleness and femaleness are categories of gender identity, a gnostic sense of one’s identity that is perfectly knowable by the individual but not verifiable or falsifiable by others, even in principle. The paradox is that this concept has no meaning apart from a common, pre-woke understanding of male and female—but that basic biologic understanding is itself anathematized in the faith. Even if Jackson didn’t believe the dogma herself, she could not deny it and remain in good standing in her faith. To ask her what a woman was is sort of like asking a Catholic judge a tricky question about transubstantiation.

But there is a key difference, at least in modern times: virtually no one intends that the law will ever require non-Catholics to live as if the doctrine of transubstantiation is true. This is because Catholicism is contextualized in our society as a religion, and people are thus entitled not to believe in it. On the other hand, contemporary American progressivism is not contextualized as a religion, or even as a worldview—to believers, it’s understood as “literally just being a decent person.” Accordingly, they expect everyone to live as if their beliefs are true.

In this way, contemporary American progressivism wants to have it both ways: it wants the privileges rightly claimed by believers against intrusive questions about one’s deepest spiritual beliefs, but also wants its dogmas to be made normative for everyone. It should be one or the other: if you want a belief of yours to be binding on others, you should defend and answer questions about it (think of Catholics on abortion). If, on the other hand, you want to shield a belief from criticism or even inquiry, you should avoid arrogantly expecting nonbelievers to live as if it is true (think of Catholics on transubstantiation). Instead of becoming defensive or apologetic, we should treat the other religion as a peer, not as a superior who is above criticism nor an inferior too fragile for it.

And maybe there is something hopeful in this possibility. After all, sometimes a spouse committing an emotional affair doesn’t fully realize what they are doing—the faithful spouse needs to realize he or she is being cheated on and be willing to talk about the homewrecker if there is some hope of interrupting the process of abandonment. In this case, sparking reconciliation may need to begin with contextualizing the other religion as a religion and helping the disaffected awake to the fact that their church has not somehow left them, they have just joined another one.

Too often we don’t do that. Like the blindsided faithful spouse, we take criticisms from disaffected members at face value, laboriously producing responses that in most cases are ignored or simply further picked apart. The faithful spouse could be a saint, and the Church could be spotless, and the wayward partner would remain contemptuous and aloof because the fact is they are in love with someone else.

Instead of becoming defensive or apologetic, we should treat the other religion as a peer, not as a superior who is above criticism nor an inferior too fragile for it. Disaffected members critiquing our faith from within the framework of their new faith can be asked to show their cards, explain their own beliefs, and make an affirmative case for them if they want us to agree. We should stop accepting terms of debate where church members are required to justify their beliefs from within the framework of the contemporary progressive worldview, while those of the other faith can perpetually disclaim any burden of proof for theirs.

This change in approach is hard. We have been playing defensively not because we don’t want to win but because the deck is stacked against us. But it’s possible: people can be—and have been—woken up to the fact of their unintended conversion. They must be if there is to be any reasonable hope that they will return.