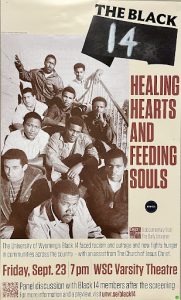

A few weeks ago, a documentary premiered in the Brigham Young University Varsity Theater entitled, The Black 14: Healing Hearts and Feeding Souls. It’s a story 53 years in the making, and although initially born of discrimination, the happy ending is one of redemption, forgiveness, and healing. It’s not the kind of story that typically gets national attention.

And this one didn’t. That’s unfortunate. Despite national headlines that focus on negative accusations and controversial claims about BYU, the school is getting a lot of really important things right.

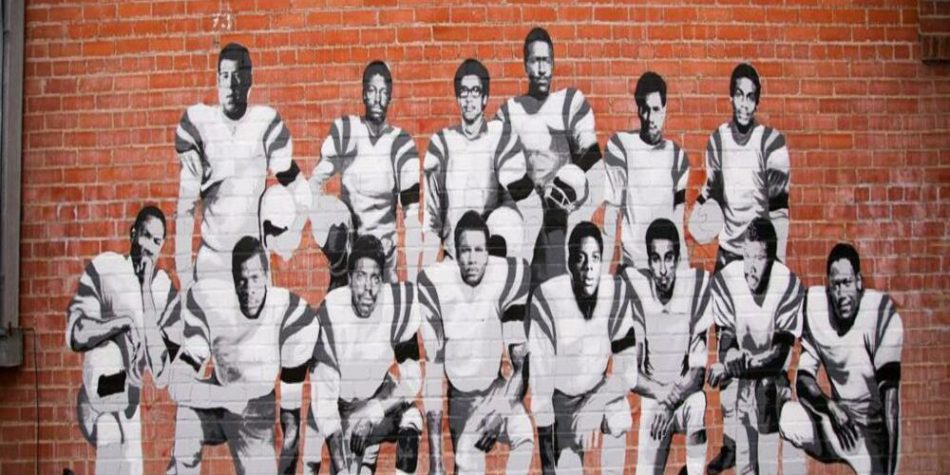

Pointing to exactly what America needs. BYU Journalism professors Alan Neves and Melissa Gibbs, along with five of their journalism students, worked for over a year to gather the story of The Black 14. Their travel included eleven states in ten days and hundreds of hours of research, interviews, and edits. All this hard work brought together details of a profound story that began in 1969 when fourteen Black University of Wyoming football players had concerns about an upcoming game against BYU, based on policies about race by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. They wanted to wear black armbands during the upcoming game to signal their protest and approached their coach with the request. Yet they were caught off guard by an unexpected tirade of racist rage from their own coach toward the team members—including hours of berating and humiliating rebuke. This was followed by every one of them immediately being removed from the team, expelled from school, and reeling from an outcome they couldn’t have seen coming.

Understandably, years of anger and resentment plagued many of the fourteen. Although they each achieved a measure of success in making peace with the past, questions and frustration remained. Bitterness toward the school, their coach at Wyoming, BYU, and the Church was difficult to assuage. In 2019, the first formal efforts of reconciliation were made when many of the fourteen men returned to the University of Wyoming to receive letterman jackets and an official apology. As part of that visit, a relationship with The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints began when students from the Church’s affiliated Institute of Religious Studies also invited them to speak and, in a gesture of goodwill, welcomed them by wearing black armbands to the event. Later the former players were hosted in Salt Lake City, Utah, by Elder S. Gifford Nielsen, a General Authority Seventy, himself a former BYU quarterback (who played several years after the controversy). As part of that meeting, a sincere question of how the Church could help was answered by Mel Hamilton, one of the fourteen. He and several of the other men had begun an effort to help with food insecurity in their communities, and he wanted to know if the Church could do anything to help in that effort. A truckload of food and supplies from the Church went a long way to feed souls and heal hearts. The documentary tells this story in play-by-play detail and packs a punch—inspiring in its viewers a desire for continued efforts and participation in good-faith racial reconciliation.

I arrived early to see the premiere of this documentary, planning to stand in line for a seat and hoping not to get ushered to the overflow. But, worries unfounded, I easily got a seat toward the front of the theater. Posters, invitations, and press releases to the public resulted in the auditorium filling to about two-thirds of its capacity. A couple of rows in front of me sat President Worthen, along with administrators from the Business, Communications, and Athletics departments. Guests from Church Public Affairs, the University of Wyoming, and, most exciting, two members of The Black 14 were there. It was a meaningful event that merited significant time and attention.

Distracted by the drama. I wasn’t the only one who responded with emotion to the film, and I participated in a standing ovation at the conclusion of the live thirty-minute Q&A that followed the documentary. Many stayed to visit with other guests afterward, just wanting to linger in the goodwill displayed. It was one of those moments you just want to share with others. But where were they? Media reps, journalists, and lots of others? Where was the crowd? Why wasn’t the theater and overflow packed?

The story was filled with everything culturally relevant; a thoughtful study of history that provides a concrete illustration of actionable solutions for the future—but critical guests were missing, and I couldn’t help but feel disappointed.

Even so, I recognize criticism and controversy are sure paths to attention—evident in the recent news cycle. Indeed, a review of national headlines about BYU in just a little more than a month reveal plenty of attention for critics like a Duke volleyball player, Oregon fans, pamphlet distributors, disgruntled employees, and the Black Menaces (who were invited to the screening but seemed to have more pressing engagements). In each case, there’s seemingly plenty of time for staging and reporting protests and stirring the collective pot of mounting American hostility, but that doesn’t leave much time and interest for an event that features hope and healing.

Why is that? Honest question. We hear so much these days about mounting racial hostilities. In a day and time when there are so many fears about these escalating conflicts, you would think that any concrete illustration of a better way would be received like water in a parched desert. It certainly felt that way to some of us in attendance. Yet the reality is that for far too many people, the conflict is what they’ve signed up for. And if your attention, energy, and resources are going towards that, it’s understandable why you’d not only have little bandwidth for anything else—you might even see the hard, soul-stretching work of real racial reconciliation as, at worst, a threat, and at best, a distraction (the revolution calls!).

Appreciating the innovative steps being taken. I’m writing not as an apologist for BYU but to ask that we give credit where credit is due. This documentary and the hospitality surrounding it represented encouraging opportunities to focus on the positive and were hosted in part by BYU’s new Office of Belonging. Blake Fisher, an administrator in the new office, explains how this office is different from what one might typically think of as Diversity and Inclusion efforts. As Elder Clark Gilbert has said:

The DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion) programs in the world are not the way BYU should do it. We should find a gospel-centered approach. We should be better than we are now, and we should be a light to the world but not replicating the world.

University President Kevin Worthen has also recently elaborated, “Our belonging plans and efforts will be based on gospel principles at every step. That will necessarily mean we do some things differently than would be done in other places.” He then underscored the importance of “ensur[ing] that we remain in alignment with gospel methodology, concepts, and insights” in a way that “will help us avoid the divisive and polarizing forces generated by some approaches to this important issue.” Ultimately, he reminded the audience the aim is to “have a truly unified, and unifying, gospel-based belonging effort that will have long-lasting effects.”

Saying more about diversity and inclusion, Fisher told me, “They are beautiful ideas but not the goal. Diversity at its root is a focus on the ways we are different. We are working to create a place where everyone feels they belong by placing emphasis on our common purposes and goals as a body of Christ. In that effort, language matters.” As he continued. “So we are rethinking invitations, processes, and initiatives,” admitting that they won’t always get it right but reassuringly adding that “there are a lot of things going well.”

It’s true there are deans, professors, students, parents, and interested members of the community (across the spectrum of opinion) who will be watching this new office very closely. Some will be looking for secular creep, while others are concerned that legitimate episodes of discrimination will be ignored. Either way, Fisher assures that the office won’t mind being held accountable to their Statement on Belonging, which reads as follows:

We are united by our common primary identity as children of God (Acts 17:29; Psalm 82:6) and our commitment to the truths of the restored gospel of Jesus Christ (BYU Mission Statement). We strive to create a community of belonging composed of students, faculty, and staff whose hearts are knit together in love (Mosiah 18:21) where:

- All relationships reflect devout love of God and a loving, genuine concern for the welfare of our neighbor (BYU Mission Statement);

- We value and embrace the variety of individual characteristics, life experiences and circumstances, perspectives, talents, and gifts of each member of the community and the richness and strength they bring to our community (1 Corinthians 12:12-27);

- Our interactions create and support an environment of belonging (Ephesians 2:19); and

- The full realization of each student’s divine potential is our central focus (BYU Mission Statement).

Admittedly, the efforts of this office are positioned for criticism from both within and without. But Fisher is hopeful. “People come with a framework that’s different from what we are trying to do. We believe it is possible to stress primary identities that honor individuals and align with principles of truth. And if we can accomplish this, the Office of Belonging could really help us all prepare to live together as a Zion people.” Die-hard critics aside, elements of Zion were on display at the premiere, and the goals of belonging are worthy of attention. Next time, if we can pack the house, I’ll happily sit in the overflow.