Americans have always been divided over politics, but the divide seems to be getting worse. Members of the two major political parties overwhelmingly see members of the other party as “immoral” and “dishonest,” according to Pew Research. Approximately 11% of Americans are less likely to support a topic if they think there is bipartisan support for it, a YouGov poll found. For at least 11% of the electorate, not letting the other guy win is more important than winning.

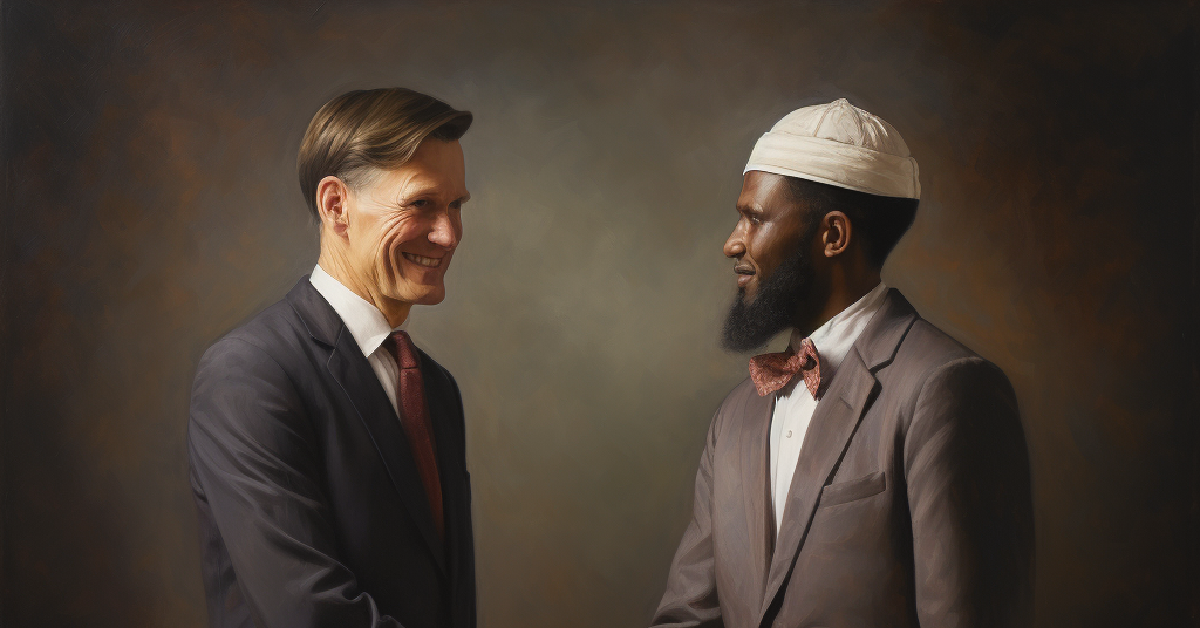

But focusing on the statistics of divisiveness too much can obscure a different truth: Americans are not as divided as they seem. In fact, there is near consensus among Americans on a range of important political issues. Americans need to begin to see the political spectrum not as two sides split down the middle, but as a large block of consensus with extreme ideas at the ends of the opinion spectrum. Approaching political controversies from a perspective of unity rather than division is the first step to resolve the urgent political challenges we face today.

Americans are not as divided as they seem.

Media biases are well documented by groups like Ad Fontes and others that study media biases. Many modern media conglomerates combine incomplete facts with biases to present a cultivated reality, as several organizations have shown. When outlets are so skewed, the citizenry splits.

President Dallin H. Oaks has also spoken of the dangers of division. In a 2023 address at the University of Virginia, he observed, “Extreme voices influence popular opinion, but they polarize and sow resentment as they seek to dominate their opponents and achieve absolute victory. Such outcomes are rarely sustainable or even attainable, and they are never preferable to living together in mutual understanding and peace.”

The result of this manufactured contention is division among Americans. Pew’s repeated values index shows the share of Americans at the ideological “tails” of the political spectrum roughly doubled from 1994 to the mid-2010s, with shrinking overlap between parties. The public is sorted more by party identity and values than in the 1990s, people feel colder toward the out-party than before, and elected officials vote in more unified, polarized blocs. Not only are politicians unwilling to work to achieve bipartisan successes, but prominent political leaders and media demonize their opponents.

In contrast, President Russell M. Nelson repeatedly called upon us to be peacemakers:

“Too many pundits, politicians, entertainers, and other influencers throw insults constantly. I am greatly concerned that so many people seem to believe that it is completely acceptable to condemn, malign, and vilify anyone who does not agree with them. Many seem eager to damage another’s reputation with pathetic and pithy barbs! . . . Anger never persuades. Hostility builds no one. Contention never leads to inspired solutions.”

Are Americans really as divided on the issues as we are led to believe? No! Though this may come as a surprise, there is unity and consensus in America if we are willing to look for it. Some of the hottest political topics this year enjoy agreement from the overwhelming majority of the country. For example, 91% of Americans agree that protecting the right to vote is “extremely important,” according to a recent YouGov poll. Americans also overwhelmingly agree on establishing terms limits for Congress, capping annual out-of-pocket costs for prescription drugs, increasing federal funding to improve cybersecurity, and many other issues.

In spite of broad agreement among the electorate, political topics are often politicized, and the electorate and its representatives become divided. Yet the majority of both major parties agree on at least 109 policy proposals, according to a recent YouGov poll. In many cases the government actively works against the will of the people by neglecting this consensus.

A few examples of the 109 areas of agreement include:

- Increasing federal funding for public school accommodations for students with disabilities. Approximately 86% of respondents agreed federal funding should be increased for schools to support students with disabilities. This is a consensus opinion. Those who disagree are on the fringe on the topic.

- Requiring presidential candidates to take cognitive exams and disclose the results. 80% of all respondents think there should be a cognitive exam given to presidential candidates and those results be published before a candidate can be elected. That is a massive consensus.

- Increasing funding for the maintenance of national parks. 80% of respondents agreed that the federal government should spend more on national parks. The value of such parks is recognized globally and Americans overwhelmingly want their parks protected.

Areas of agreement exist for even the most controversial topics, such as abortion. For example, ninety-two percent of Americans agree that abortions should be legal in at least some cases. On the other side, seventy percent agree that elective abortions should not be legal in the third trimester. This consensus could be the beginning point of more productive discussions about preventing and regulating abortion.

If there is common ground on abortion, there is common ground everywhere. On nearly every political issue, points of common acceptance and understanding can instigate paths to consensus solutions.

There is common ground everywhere.

To be sure, we will not be able to resolve all political challenges in ways that make everyone happy. But that does not absolve us of our obligation to make a good-faith effort to find inspired solutions. President Oaks said, “As a practical basis for co-existence, we should accept the reality that we are fellow citizens who need each other. This requires us to accept some laws we dislike, and to live peacefully with some persons whose values differ from our own. Amid such inevitable differences, we should make every effort to understand the experiences and concerns of others, especially when they differ from our own.”

As followers of Jesus Christ, we can follow the counsel of our modern prophets as well as the example of our Savior, Jesus Christ. We start by respecting those around us and seeing them as our fellow brothers and sisters, in spite of their political positions. Satan seeks to divide us using geographical, societal, and political divisions to inspire disharmony. Rejecting labels placed on others for political reasons helps us to see situations—and others—more clearly.

True study of the issues, challenges, and potential solutions will drive us to open our minds and recognize what we have in common both as citizens and as children of God. The General Handbook of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints teaches us to “seek out and share only credible, reliable, and factual sources of information.” Following this counsel will naturally drive us to limit polarized sources and seek out real truth, which likely requires engaging multiple perspectives and opening our minds to accept truth when we see it. When we start from the assumption that there is common ground, we can break free from the bifurcated political landscape in which we live.

Satan seeks to divide us.

“We urge you to spend the time needed to become informed about the issues and candidates you will be considering. Some principles compatible with the gospel may be found in various political parties, and members should seek candidates who best embody those principles. Members should also study candidates carefully and vote for those who have demonstrated integrity, compassion, and service to others, regardless of party affiliation. Merely voting a straight ticket or voting based on “tradition” without careful study of candidates and their positions on important issues is a threat to democracy and inconsistent with revealed standards (see Doctrine and Covenants 98:10). Information on candidates is available through the internet, debates, and other sources.”

Leaders of the Church of Jesus Christ have delivered repeated prophetic counsel. Our duty as followers of Jesus Christ is to actively fulfill it by becoming peacemakers. So the next time you find yourself feeling outrage or contempt for what “they” think or do, remember: you probably agree with them on a lot of issues. The divide may not be as wide as you imagine. If we’re willing to look, perhaps we’ll find that “they” are standing right next to “us” on some important political topics. Peacemaking starts by rejecting the voices that look to divide us, recognizing what we already have in common, and building from there.