The Big Idea: Behind all our beliefs or claims about the truth, there looms the often-unacknowledged figure of Authority. Sometimes it is not possible to effectively consider the truth of a claim without dealing with the authority we trust that supports it.

As we have seen in our previous exploration about truth, rarely is the question—“Is that true?”—posed of the opinions under discussion. Yes, sometimes people say (of other people’s opinions) “that’s not true!”, but rarely does it occur to them to use that all-essential question as a way to frame the conversation itself, as a way to consider … and then reconsider … what is being claimed. Rarely is this curiosity appreciated as something different people could (if they so chose) have in common: namely, the desire to seek the truth, the whole truth, together.

But, even when the question “is it true?” is explicitly and consciously posed, there is another shadowy figure looming behind the opinions being expressed, forming the very basis upon which the disputing parties hope to establish the veracity of their opinions: “authority.”

Take, for example, the issue of marriage between people of the same sex on the one hand, and the issue of global climate change on the other. On the issue of marriage between people of the same sex, many people who are against it (though not all) base their objection to it on the principles of their religious faith, the authority for which they variously ascribe to a supernatural God or to a particular tradition (written or oral), or to certain human beings considered to be uniquely worthy of trust or reference (e.g. ancestors, gurus, etc.). Some religious people have a more internal “personal witness” view of authority, and thus refer to what they might call their own “higher self/Self,” or “inner light,” or “inner moral compass.” Other people who are against ‘gay marriage’ claim for the authority behind their position something more like natural law, or even personal conscience. While still others point towards reason and science as a reliable support—a kind of reliable authority—for their views as well.

Interestingly enough, people who are supportive of marriage between people of the same sex can and do locate the authority for their beliefs in all of the same sources as those who are against it. Many who support marriage between people of the same sex cite for support of their views all of the same authorities as those arguing against it: God, gods, ancestors, gurus, tradition, natural law, tradition, personal conscience, and science.

To take just one example, albeit a politically prominent one, “the” Bible (which Bible—the Jewish, the Protestant, the Roman Catholic, or the Eastern Orthodox is less often specified) is quite frequently referred to as an authority on the issue of marriage between people of the same sex both by people arguing for pro-gay theologies and by those arguing against it. (During the Civil War, it should be noted, the same occurred for and against slavery.)

On the issue of climate change, likewise, for those who ascribe to the theory of its being human-caused and detrimental (catastrophic even), the authority they appeal to most often (though not exclusively) is “science,” or what they refer to as “the scientific consensus.” (Whether their position, in reality, represents the scientific consensus, or whether this scientific consensus can itself be trusted, is part of what is debated.) Others (e.g. religious people of all sorts, or people steeped in some indigenous spiritual traditions, or pagan earth-centered traditions) may find the source of authority for their belief in detrimental anthropogenic climate change in all the same sources as listed previously: God, gods, divine beings, ancestors, tradition, personal witness, etc.

Likewise, those who do not believe in detrimental anthropogenic climate change can be heard to claim authority for their opinion in all of the very same sources as those who do believe in it: science, God, gods, divine beings, ancestors, tradition, personal witness, etc.

We thus find ourselves standing on what could be called a “battlefield of truth convictions or claims” regarding the nature and moral standing of marriage between people of the same sex, and regarding the issue of climate change, while witnessing a truly bewildering spectacle: various and sundry armies, legion in number, fighting each other in the name of—under the banner of—the very same sources of authority!

Surprisingly enough, often overlooked in the controversies which rage over such issues—be it the issue of same-sex marriage, climate change, abortion, domestic violence, the 2nd Amendment, UFOs, or the role of American power in the world, etc.—is how inescapable some reference to authority is (even if it is only the authority of one’s own personal conscience or reason). In other words: we humans invariably refer to some authority (however tenuous or fallible we might consider it to be) when coming to our opinions, and when engaged in conversation/discussion/debate with others regarding any issue. But whether or not those authorities are in fact reliable is often not questioned by those appealing to them. Interestingly enough, the reliability of those authorities is sometimes not even questioned by the people arguing against the opinions that people are trying to support by appealing to them. In fact, nearly all scientific facts require interpretation in order to make them meaningful.

Looking at the fraught issue of the right form of marriage, the situation is really not much different. For example, many that affirm the superiority of heterosexual marriage and many who do not, each claim to rely on the latest scientific consensus for the authority underlying their views. Again, an extremely small number of us are in reality, in truth, scientists practicing in the relevant fields (be it sociology, anthropology, biology, genetics, or epigenetics). Our conversations/discussions/debates on the issue are therefore inextricably tied to our own non-professional interpretations of “the experts.”

Complicating matters even more, there are people who do not even acknowledge the role of interpretation when it comes to gleaning guidance from their chosen source of authority: there are billions of people (both liberal and conservative) who say “The scripture says …” (or “the Constitution says …”, or “the data indicate …”), and leave it at that, without acknowledging their own role (via interpretation) in determining what they think the text (or the data!) means.

Once again, these arguments over correct marriage forms often have a bizarre quality as people on both sides point to the same “holy scripture” in order to justify their conflicting points of view. Each claims for their interpretation the imprimatur that comes with being aligned with what they claim is a text having the authority of God behind it. Without engaging more directly with each other’s interpretations as interpretations (rather than as “what the scripture says”) opponents woefully miss the chance to gain mutual understanding about the way they came to their interpretations (e.g. the personal experiences that led them to interpret scripture in different ways). This understanding of how opponents came to their convictions over correct marriage would allow at least for productive conversations over different value priorities (based on interpretations of reliable authority) as they influence controversial practical policy issues.

Similarly, on both sides of the climate debate, people sometimes refer to “the facts,” as if facts can stand on their own, and interpret themselves. In fact, nearly all scientific facts require interpretation (called “theory” when the interpretation is robust enough) in order to make them meaningful.

Let us, therefore, at the very least, recognize that “authority”—a source of reliable guidance—is the most common basis for our beliefs and convictions. Let us, at the very least, dignify our political enemies and religious enemies and scientific enemies by acknowledging that they are likewise human beings seeking reliable guidance in a bewildering world of conflicting truth claims, and that, in this bewildering world, we ALL—ALL of us (without exception)—seek reliable guidance of some sort. We ALL have chosen authorities we refer to and rely upon. And let us also acknowledge that while we must personally interpret their guidance, we all—liberals, conservatives, and independents—acquiesce to the directions of our chosen authorities. Indeed, our own conscience requires that “we” attend and choose to obey it, and our own interpretation of the guidance we take from it.

Challenging authority. While these various and sundry authorities should be acknowledged, they, obviously, cannot all merely be “accepted,” at least not when they are being used to support views that are being contested and are under scrutiny. Neither can they be categorically considered “out of bounds” for a challenge. In fact, a primary focus of public deliberation and debates ought precisely to be a kind of collective scrutiny of competing sources of authority. This is true of authorities like “the Bible” and authorities like “personal conscience.” For example, if Christians wish to have the Genesis account of human origins made part of the public school curriculum, then they must also accept public scrutiny of the claim of Biblical authority. After all, the inclusion of Christian scripture in a public education setting has public consequences, and hence—if one ascribes to the basic democratic social contract undergirding our collective life in America—the public has a right to challenge and scrutinize anything that affects them. Likewise, if gay activists wish to make their personal witness or experience of their sexuality the source of authority to which they appeal on the issue of marriage, then that authority too, must be open to full public scrutiny. After all, marriage has public consequences too.

Is authority X reliable or not? In other words, does authority X in fact, in truth, provide reliable guidance on what is true, what is real? Too often our conversations/ discussions/ debates attempt to sidestep this question. People (especially people on the so-called “left” end of the worldview spectrum) sometimes try to debate deeply value-laden issues or politically fraught subjects like marriage and the global climate without getting into the ‘weeds’ (or going down the ‘rabbit-hole’) of whether the other side’s authority (e.g. “the Bible”) is reliable or not compared to their own presumptive authority (e.g., rational-empirical science). And yet, is a serious engagement over differences based on conflicting authorities even possible without engaging each other on the alleged reliability of the authorities looming behind our various and sundry opinions and positions?

We would argue that, in fact, it often is not. Naturally, it is possible to find practical ways to argue with conversation partners only on matters where we do accept the same authority by cordoning off areas where we do not. We do not need to fully agree on the validity of all our sources of authority in order to have a sufficient level of agreement on some sorts of authority (e.g. the authority of reason itself) which enables us to find ways to live together without immediately coming to blows. For example, both people in favor and against the theory of anthropogenic climate change might share sufficient faith in the authority of science to believe that coal dust in the air is not a good thing to breathe and that cleaner air is desirable. In this case, we could find agreement on what could be called the level of “adequate or sufficient truth.” Certain aspects of the climate change issue probably lie within the reach of an “adequate truth” level for agreement (everyone wants clean air, for example).

However, for clear understanding, conversants need to acknowledge very real disagreement about the nature and reliability of that authority called the “scientific consensus.” Therefore part of the conversation still needs to be at the level of scrutinizing the reliability of the supporting “authority.” Indeed, deeply felt attitudes towards the authority of “scientific consensus” remain perhaps the primary obstacle to more productive conversations on this politically fraught and scientifically complex issue. But, at least in theory, most people on all sides of the issue, have some confidence in the value of “science” writ large and share the values of a liveable, sustainable ecology, and the importance of human stewardship of natural resources. So there is room for deep conversation here without venturing into sources of authority upon which there may be less widespread agreement (e.g. a politicized “scientific consensus,” scriptural prophecy regarding the end of the world, extra-dimensional or extra-terrestrial revelations regarding potential sources of planetary healing or renewable energy sources, etc.).

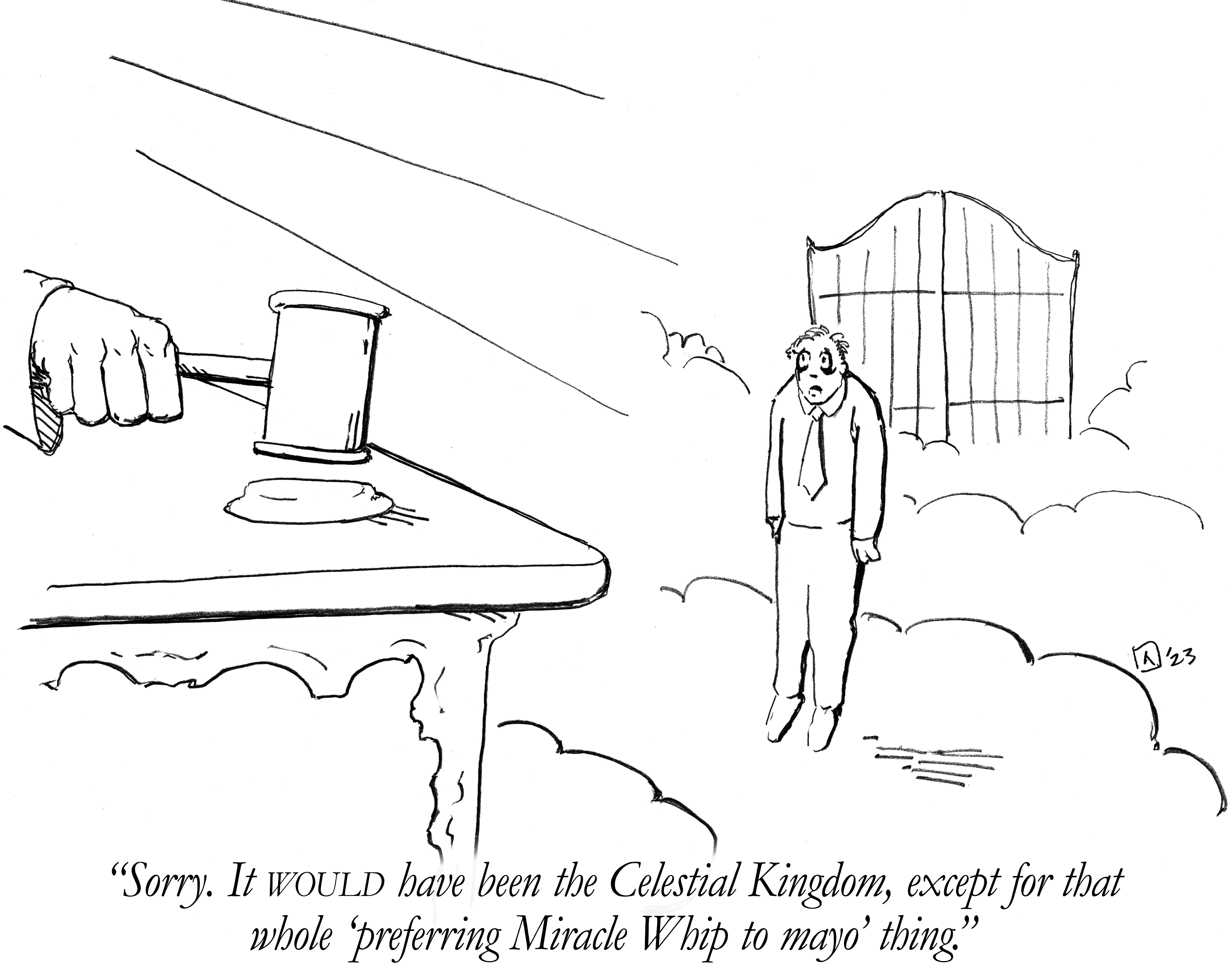

However, for the issue of marriage between people of the same sex, there may be less territory immediately available for cross-worldview conversation that does not first require passing through weedy and formidable mountain ranges where Authority-Writ-Large (and Identity-Writ-Large) weighs heavily on potential conversants’ decision to even desire to listen to each other. For conservative religious groups like Latter-day Saints, pro-gay theology, if true, very strongly questions the very deepest structures of spiritual authority within their church (thus threatening the very foundation upon which pious orthodox LDS individuals with “same-sex attraction,” as they would call it, have chosen to structure their lives, some of them with marriages to people of the opposite sex—marriages with children—at stake; Most pious Latter-day Saints believe mortal heterosexual marriage is not just a moral norm; it reflects the highest embodied social form of Gods, so any other form than that—single or married, is deficient.)

On the other hand, if orthodox Latter-day Saint teaching about marriage is true, then the very personal self-identities of “LGBTQ” people, as they might call themselves, are at stake—with similar painful endings of lives and relationships possible. There is no “more loving” path than the path of truth.

Death is already inevitable. Better, therefore—we assert—death on the path of truth, on the battlefield of truth, rather than death by deception, falsehood, untruth.

There is no “more loving” path than the path of truth—a path that often leads to honest critical battles of persuasion between rival authorities on the field of truth claims. Too much is at stake, and as we have asserted, people will likely die and lives likely destroyed, no matter what the whole truth, in reality, is—if for no other reason than that some people will prefer to live in lies they have believed too long rather than to face the earth-shaking shock of truth.

There are, therefore, times when it is the very source of authority itself which factors in so largely to the question of truth that disagreement about its reliability MUST be part of the discussion. The issue of marriage between people of the same sex is only one of those issues.

Reprising the example of the Latter-day Saints, the authority which the orthodox leaders of the Church claim (LDS scripture, living prophets, etc.) is unsurprisingly the object of the most ardent and direct challenges by those who claim that truth is on the side of pro-LGBTQ theology. Of course, one may, for strategic reasons (including the desire to be kind to people involved in the issue), choose to go about this less forthrightly. One may, as some are presently doing, choose to try to bring to the attention of such orthodox leaders the scientific-authority-backed facts (as they see it) of the suffering which conservative beliefs impose upon LBGTQ people (e.g. statistics about suicide), while ostensibly claiming to not be asking those leaders to “disavow their beliefs.” But, the position of the authors of this book—the position we are trying to convince you of and persuade you to adopt—is that all ‘sides’ are best served by being honest and truthful, in as transparent a manner as possible, even when that leads us to ask ourselves and others to deeply examine bedrock assumptions about the authorities that present the truth we trust to guide our lives.

That means first, questioning with heart and mind why we now grant authority to some and not other truth-claimers; and then crucially, acting with conscientious integrity based on our answer. We humans do not have the luxury to live indecisively no matter what we like to tell ourselves. Each instant of our waking existence records what we have done or not as our responsibility. When we tell ourselves we are ‘uncommitted’ life carries an action camera that demonstrates how much our moment-by-moment choices depend on who we trust—and what authority we have deemed reliable.

Therefore, as we seek the whole truth together, let us forthrightly acknowledge to each other why we follow our current masters—those to whom we trustingly grant the authority to order our lives. Who are they? Our Facebook buddies or scientific/professional experts or political pundits or family loved ones or spiritual leaders or the still small voice within that some call conscience and some call God? This mutual self-awareness and disclosure reveals conflicting authorities and allows our conversations to be deep and refreshingly on point, our conflicts focused on the center of the knot that begs to be untied, and, most importantly, our mutual trust to bloom—even if the knot remains as tight as ever.

The Big Invitation: Next time you find yourself wanting to persuade someone of something, or you find yourself in the presence of someone wanting to persuade you of something, pause and ask yourself what “authority” or “authorities” are being appealed to, either explicitly or implicitly, in order to make the argument more persuasive.

Then, consider whether or not the conversation might need to shift to focusing on that authority and on the relationship which you and your conversation partner have to that authority. Share with your partner what that authority means to you, and why it is important to you…and learn the same of their relationship to whatever authority they are proposing (either consciously or unconsciously) as being worthy of your attention.

There is often a lot at stake when it comes to examining one’s most cherished authority, so tread lightly when challenging the worth or reliability of each other’s authorities…but do not be too quick to pull back from such challenges out of the desire to be “polite” or “not rock the boat” or “not hurt someone.” People are already being hurt by conversations and discussions and debates in which these various and sundry authorities play a crucial role. If an authority is actually part of the argument, then it must be examined, and, if need be, challenged directly.

Therefore, as you’ve heard us say before, make truth your aim. Yes, be gracious and kind whenever possible, keeping in mind, however, that in so many cases the truth is, ultimately, the only real kindness. Perhaps the words of St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross (Edith Stein) can serve as guidance here:

“Do not accept anything as the truth if it lacks love, and do not accept anything as love which lacks truth! One without the other becomes a destructive lie.”

We would add: do not accept the word of any authority if it lacks love, and do not accept the word of any authority if it lacks truth. Though in some spiritual traditions we are told not to “test” God, and clearly we cannot expect to be the final arbiters of the truth claims of authorities whose “expertise” (if you will) by definition transcends our own ability to know; perhaps even then, any and all claims made by authorities claiming to represent God (or, in more secular contexts, claiming to represent a trustworthy source of truth) should nevertheless be put to the test, in the crucible of conversation with others seeking the whole truth, together.

Keep in mind that “love” isn’t always “nice” or “polite”, and that sometimes the truth, even if spoken in love, can hurt. We will often disagree deeply in our opinions about what is true or not, what is loving or not, so without the willingness to risk hurt—without the willingness (treading lightly, carefully) to shake even the foundations of our own and others’ perceived security—there will be neither real love offered nor truth shared…nor true security.